Back to

Home page

Linked from

The Village Voice

New York, 1957-74

A writer friend, Betty Rollin, took me to meet Dan Wolf and Ed Fancher, the founders and, respectively, editor and publisher of The Village Voice, late in 1957, little more than a year after I arrived in New York. The Voice was barely two years old, a Greenwich Village community weekly that had special cachet because Norman Mailer, a friend of Dan’s, had initially written a column for the paper, attracting attention and a number of exceptional writers. Circulation was small, and paying the printers and staff would be touch and go for several more years, with contributors paid nothing at all. I volunteered to do whatever needed doing. They needed a sports car column, and I said I could write it, though I did not have a sports car, my only qualification frustrated desire. Over the following months Dan assigned me a few stories and put me to work around the office, helping to prepare copy for the printer and read proofs, even covering for the bookkeeper when she took a vacation.

The paper was slim, sixteen or twenty pages, occasionally as few as twelve. Dan edited the first four pages, containing the news, letters, and Jules Feiffer’s weekly cartoon. The rest of the editorial content was produced by Jerry Tallmer, the associate editor, who took me under his wing and, alongside Dan, mentored me into the newspaper game. Jerry was also The Voice‘s theatre critic, a role he took seriously—he won a George Jean Nathan award for the excellence of his reviews—and theatre was given perhaps disproportionate space in his pages. Jerry admired the Living Theatre and had a taste for boldness and innovation, and he made The Voice Off-Broadway’s champion: with Dan and Ed’s support, he initiated the Village Voice Off-Broadway Theatre Awards (“Obies”) in 1955, bringing together the growing downtown theatre community for an annual party.

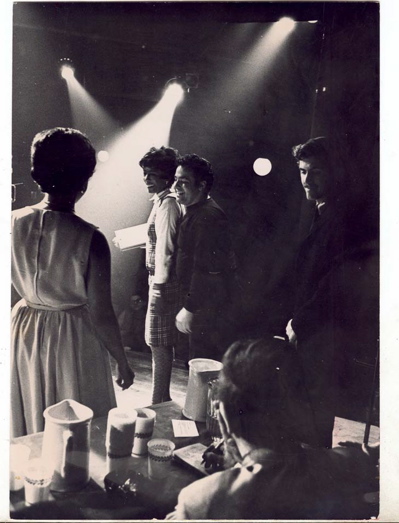

At the Obies, 1965: Ellen Stewart and Joe Cino recognized for creating new opportunities for playwrights; at left, Gloria Foster, the presenter; at right, MTS; foreground, Dan Wolf.

I began writing for The Voice in 1957; then in 1958 I was drafted. No longer protected by being in college, I passed the physical in New York and went to California to be inducted. Only at the last minute was I deferred for obscure psychological reasons. Soon after I got back to New York, I reviewed a couple of books for The Voice—one was Kerouac’s “On the Road.” Then Jerry asked me to review a play for him—I have a vague memory of “Macbeth” in the vaulted basement of a church—and that was the beginning of what became my most illustrious and consuming public identity. Reviewing plays was the perfect combination of my two main career interests, writing and theatre. Soon I was The Voice’s regular second-string critic, covering whatever Jerry did not have time or inclination to see. He was a superb editor, with high, strict standards of good writing; he taught me to be concise and focussed: I sometimes had only three or four inches for a review.

The paper gradually took hold and after a couple of years my copy-editing and proofreading turning into a job. I helped Jerry in the office, and for years I went to the printing plant, on Long Island and later in Jersey City, every Tuesday night to put the paper to bed, carrying the last copy and proofs, reading galleys and page proofs, checking corrections on the stone, staying until everything was as perfect as I could make it, often three or four a.m., before the presses could roll. When Jerry abruptly quit The Voice in summer 1962 to take a job at the New York Post (then an admirable liberal paper), Dan took me for a walk from the office on Sheridan Square over to Washington Square, sat us down on a bench, and offered me Jerry’s job.

The following winter the seven New York dailies were on strike for almost four months, from December 8 until April 1. The Voice began distributing citywide and leapt ahead. There was no place else to put classified apartment ads, for one thing, and I was one of few critics reviewing plays. We rarely had more than twenty-four pages before the strike; we jumped to thirty-six, forty-eight, sixty, seventy-two. It must have been extraordinarily hard work, but my personal life was so exciting at the time that I hardly noticed, I just rolled with it. It took three of us at the plant to proofread pages. Circulation rose to eighty thousand, and we held onto most of it after the strike was settled.

I now had first pick of plays to review, and I often saw four or five in a week. There was much more room in the paper, theatrical horizons were opening up, and I kept three or four other reviewers busy as well. I had Jonas Mekas and Andrew Sarris writing about film, Jill Johnston writing about dance, …

Great theatrical art was still to be seen on Broadway in those days, the Living Theatre on Fourteenth Street was increasingly political, and new plays and styles were starting to pop up in such improbable places as the Caffè Cino, an Italian coffee house on a quiet Village sidestreet, Judson Poets’ Theatre, in the choirloft of a church on Washington Square, Cafe La Mama in an East Village basement. Before long a fresh generation of playwrights, directors, actors, impresarios, and personalities had emerged, and I was in the middle of them.

Obie Judges 1972: front row, Julius Novick, Dick Brukenfeld, Martin Washburn; back row, John Lahr, Michael Smith, Arthur Sainer, Michael Feingold (photo: Fred W. McDarrah)

By 1965 the relentlessness of putting out a paper every week was wearing me down. I had written a play and directed a play and I wanted to do more. I also wanted to travel. When I left for a trip to Morocco that summer I ceded my editing job to my assistant, Diane Fisher, who later shared it with Ross Wetzsteon, who had assisted me proofreading and took over going to the plant. I held onto my perks as chief theatre critic and kept running the Obies. I kept writing reviews, and later a column, Theatre Journal, for The Voice until 1974, with a two-year break in 1968-70, when Ross took over the Obies. I did a little more production work for the paper in 1973, when it was going to cold type and bringing the composition in-house. By then Dan and Ed had sold The Voice and the old camaraderie was attenuated, to say the least. Something similar had happened to Off-Off-Broadway, which had blossomed into dozens of venues and largely lost its edge, turning into a “showcase” and commercial launching pad. The culture as a whole was sick, and I was sick of reviewing. After one more season I moved out of the city and did other things.

Reviewing for The Voice was a great job. I got to see hundreds of plays, not only in New York but elsewhere in the country and on multiple trips to England and the Continent, one trip around the world, though The Voice did not pay for any of my travels. I was the Michael Smith, and the Voice connection opened doors: I edited three anthologies of new plays and put out two books of critical journalism. It also took over my identity. The fact that I wanted to be a playwright and a director and a lighting designer more than I wanted to be a critic could not change the fact that I was more useful to other people writing about their work in The Voice than I was doing my own work. To this day people in the theatre think of me primarily as a critic, if they think of me at all, though it is more than thirty years since I wrote a review for The Voice.

I had to reject my critic self in order to move on, and for years I nursed a somewhat negative attitude to that phase of my work life. Lately I have come to appreciate it, thanks largely to Steve Bottoms, a young theatre professor then at the University of Glasgow, who came to see me in California twice as part of his research for a book on Off-Off-Broadway in the sixties, a body of work that had received little academic attention. I had long thought that I should write a book about Off-Off-Broadway myself, since my position at The Voice gave me a unique overview of the scene: for several years I tried to see everything. Steve would do it better. He dug up (and quoted from) many of my reviews, and I shared my memories, observations, and understanding of the scene as fully as I could. He talked to many other participants as well and did a marvelous job of telling a complicated story. His serious attention and analysis honored the work, as it well deserved—and made me feel much better about the whole thing.

From the Preface to Playing Underground: A Critical History of the 1960s Off-Off-Broadway Movement by Stephen J. Bottoms (University of Michigan Press, 2004):

My most important collaboration of all has been with Michael Smith, the chief theatre critic for the Village Voice throughout the period discussed in this book, whose reivews—clear-sighted, provocative, personal—I have come to appreciate as my own set of eyes on what actually happened, in performance, off-off-Broadway. Latterly, via e-mail, Michael has also stepped in as an indispensable critic and editor of my writing. Long before this personal contact was established, however, I had been struck by the frequency with which his Voice reports resonated with, and indeed helped crystallize, my own accumulated impressions of the plays and players involved. If I quote him frequently, it is because I trust him and because, still more importantly, he was trusted by the artists themselves. “He loved the theatre as much as we did,” notes playwright Megan Terry: “he let people know where to come and what was happening. When there was a breakthrough, he would be the first to proclaim it.” Smith’s unapologetically subjective reviewing style consciously eschewed the conventional notion that the critic’s function is to provide a “service” to an anonymous public, by setting oneself up in judgment over what is or is not worth seeing. Instead, always acknowledging his own preferences and interests, he sought to speak to and for the creative community of which he was a part—as a playwright, as a director, and as “key grip” for his longtime lover, lighting designer Johnny Dodd. He sought to generate debate rather than to close it down, and proved willing to open himself up to criticism in the process: “I got mocked sometimes for writing about myself,” he notes, “but it was a deliberate choice. I love the theater and wanted to be a friend of the theater and an advocate of the theater and keep the theater alive and healthy and wonderful. That was my aim—not to be right all the time.” If there is a better goal for a theater critic to aspire to, I don’t know what it is.