The Living Theatre

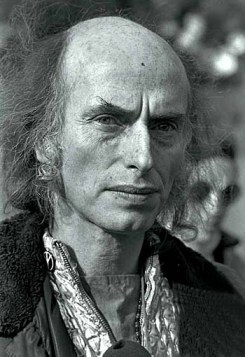

The Living Theatre opened its theatre at 14th Street and Sixth Avenue in 1958 with a production of “Many Loves” by William Carlos Williams. I started writing for The Village Voice about that time and soon became aware of the high regard my mentor, Jerry Tallmer, had for the Living Theatre’s work. I myself did not really know what to make of its poetic and experimental repertory. The directors were husband and wife, Judith Malina, a student of the German Expressionist director Erwin Piscator, and Julian Beck, an abstract expressionist painter. This was theatre as art, nothing like the show business slickness and glamor that dominated Broadway, and I was enormously energized to discover that there were other possibilities. I saw everything they did and gradually connected with “the Becks,” though it was several years before I penetrated to the third floor sanctum where they had their office and dressing rooms, much less to their apartment on West End Avenue. In addition to regular productions, they had a Monday night series that brought in poets Frank O’Hara and Diane di Prima, musicians Peter Hartman and John Herbert McDowell, dancer-choreographers Fred Herko and James Waring, all of whom were important to by developing sensibility, along with many others. Joe Chaikin toured Europe with them playing Leach in “The Connection,” and while he was appearing at the Living Theatre as Galy Gay in Brecht’s “Man Is Man,” Joe and I became friends for life.

In the early 1960s the Becks and their followers were political activists before almost anyone else, staging sit-ins to protest civil defense drills and nuclear weapons development, sometimes going to jail. In 1963, during the run of “The Brig,” Ken Brown’s hyperrealistic play about the ritual cruelty of a Marine Corps brig, the Living Theatre was dramatically seized by the I.R.S. [See my article about the consequences of this seizure in the English theatre magazine Encore, then edited by Gordon Rogoff, below.] Following the Becks’ trial, the company decamped en masse to Europe, beginning a new phase as a nomadic touring ensemble. In 1966 I went to Berlin to see their new “collective creations,” “Mysteries and Smaller Pieces” and “Frankenstein,” traveled with them off and on for several weeks, nearly joined the company to stage-manage “Antigone,” and subsequently wrote a book about the encounter, “Theatre Trip.”

Although the Living Theatre attracted large audiences and serious respect in Europe, particularly in Italy, they felt they belonged in New York, where they were needed. But when they brought their big company and European repertory to the Joyce Theatre in January 1984, they were greeted with such hostility and derision by the New York critics that the tour of American colleges was cancelled. Julian Beck died of cancer in 1985. A year later Judith Malina and Hanon Reznikov convened a group of friends to consider how they should proceed, determined to work in New York. I was a witness at Judith and Hanon’s wedding in the Municipal Building in 1988, and they opened a new Living Theatre in New York at East Third Street and Avenue C. Johnny Dodd donated dimmers and lights in memory of Julian’s beautiful lighting designs, designing lights for all their new shows. In 1989, when he was ill and no longer up to it, he asked me to take over, and I became the lighting designer of the Living Theatre. I was thrilled to have an opportunity to work with Judith and Hanon. I lit “I and I” by Else Lasker-Schüler, a wildly ambitious, epic play directed by Judith, in my last weeks of writing speeches for Mayor Ed Koch, scurrying from City Hall to the funky theatre every night for weeks to fine-tune my lighting setup, the opening repeatedly postponed, the last rehearsals running into the middle of the night.

I went on tour to Europe twice with the Living Theatre, which was more fun than anything, reviving Johnny’s lighting for “The Tablets.” I lit “Rules of Civility” in New York and we took it on the road to Italy, Spain, Germany, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. The New York media and most of my New York friends had little regard for the Living Theatre, and the only space they could afford was mean and inadequate; but they were a legend in Europe. We played in first-class settings, and it was a revelation to be respected and feted as artists, rather than scorned and dismissed. The work was demanding and rewarding. On Third Street I especially enjoyed lighting Hanon’s play “The Zero Method,” a romantic duet for himself and Judith, which they co-directed. Judith said, “Just make me look beautiful.” Hanon’s stage directions called for “light waves”: how wonderful to be handed such a challenge!

The Third Street theatre thrived for a while, with a New York company continuing there while the original cast toured abroad. Judith acted in “The Addams Family” to make money to keep it all going, but ultimately it had to close. They continued to make appearances in Europe, promoting the beautiful nonviolent anarchist revolution, working with a small company to develop new work, and performing their street play “Not in My Name” in Times Square to protest death penalty executions too many times.

Determined to have a theatre in New York, they sold the apartment on West End Avenue (originally Julian’s parents’) and in spring 2007 opened a new Living Theatre with a revival of “The Brig” at 21 Clinton Street. Tragically, Hanon had a stroke and subsequently died in May 2008. Judith and the company kept the theatre going until 2013 despite outlandishly high rent. She directed a series of plays mostly of her own authorship, including “Eureka” (written in collaboration with Hanon), “Red/Noir” (adapted from a text by Anne Waldman), “Korach,” “History of the World,” “Here We Are,” and “No Place to Hide.” Since the closing of the Clinton Street theatre, the Living Theatre has presented its work at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural Center on Suffolk Street and at Burning Man.

from Encore, Sept.-Oct. 1964:

The Artist on Trial: The Becks

by Michael Smith

The Living Theatre has fallen victim to bureaucracy and is no longer permitted to exist within the United States. It seems obvious that if Julian Beck, Judith Malina, and their followers had actually done anything harmful, they would not be permitted to exist at all; and the fact that they are now preparing to open The Brig in London and planning a tour of the Continent is proof that even the court that sentenced them to jail terms knew that their offense had been technical and not real.

“Unfortunately,” said the judge after the jury found the Becks guilty, “you have tried to reconcile your artistic sensibilities with the exigencies of tax collection, and I am afraid you have attempted an impossible task.”

This “impossible task” and its corollaries have in the past months robbed New York of access to much of the most vital and socially committed work of its artists. Apologists for the status quo give reasons galore, all technical and all trivial; but the facts are unaffected. The artists are being prevented from working and showing their work.

The Living Theatre was closed in October of 1963 for failure to pay fully its gross receipts and withholding taxes over a period of years. The Film-makers’ Co-operative was forced to suspend its public screenings of experimental films when its prime mover, Jonas Mekas, was twice arrested this spring on obscenity chrages (for showing Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures and Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’Amour) and three theatres he had borrowed were threatened with license suspension. The Café La Mama, the Hardware Poets’ Playhouse, and Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre, all devoted and persistent sponsors of new work, have been forbidden to publicize their performances and harassed in a number of other ways. The New York Poets’ Theatre, which gave LeRoi Jones his first production, produced works by a number of important younger poets, and aimed at a much-needed reconciliation between theatre and the other arts, was closed by the civic authorities; in order to reopen, its principals, Diane di Prima and Alan Marlowe, had to devote most of their energies to an elaborate membership plan which would satisfy the various City authorities which felt it to be a threat. The Artist-Tenants’ Association has threatened a wholesale exodus of artists from New York City unless the City ceases evicting artists from their loft studios; the ATA represents nearly 1200 artists faced with eviction under present zoning regulations, and the artists are forced to sneak into their buildings. Lenny Bruce is being tried—and has been extensively prosecuted already—for using ordinary expletives in his comedy routines. Ed Sanders has taken his Fuck You/A Magazine of the Arts so far underground that issues are now unobtainable. Tropic of Cancer and Fanny Hill are illegal in New York State. The most recent issue of Evergreen Review was seized by a Long Island district attorney because a woman in the bindery had complained about the “obscene” photographs it contained. Le Metro, an off-Greenwich Village coffee house where many of the youner New York poets chose to present their work in open readings, was closed for violation of an irrelevant City licensing regulation.

On subway posters and via television, we Americans are urged to donate money to CARE and other programs which help feed undernourished people in other countries; at the same time, a portion of our income is kept from us in order for the government to buy and store surplus food and keep it off the market; this tactic supports the prices of commodities, thus increasing the price of bread. Language breaks down when confronted with such paradoxes. Language is a vehicle for sense, not for nonsense.

There is a similar lack of sense in the case of the Living Theatre. The various taxes and penalties the Living Theatre owed the government amounted, at the time the theatre was seized by the Internal Revenue Service, to $28,435.10. The magnitude of the problem comes into focus when one considers that during the past season 22 separate Broadway productions each incurred losses in excess of $100,000.00.

None of the explanations makes sense. Robert Brustein suggested in the New Republic that a high-level government conspiracy—inspired by the anti-Marine content of The Brig—had led to the closing of the theatre. Others saw a connection with the Becks’ well-known pacifist and anarchist activities. (They have repeatedly been jailed for civil disobedience during protests against the annual “civil defense” drills that used to be held in America and as leaders of the General Strike for Peace.) Still others read into the apparent excessiveness of the Federal action evidence of juggernaut tendencies within the bureaucracy: that the New York office of the Internal Revenue Service was attempting to maximize the Becks’ offense in order to minimize their own overreaction to it.

Certain at no time, during or after the closing of the theatre, was there an indication that the Internal Revenue Service was actually concentrating on collection of the money owed to it. Julian Beck’s set for The Brig, which was subsequently honored with an “Obie” award, was chopped up with wire cutters. The economics of the seizure were comical: a total of about 70 men, including IRS agents and local police, were in and out of the theatre all that weekend (presumably on overtime) to prevent anyone from stealing the things they had tagged as confiscated property; and yet the auction of the theare’s physical assets brought the government only $267 toward the $28,500 debt. The theatre building itself is at present, more than eight months later, sitting unused. The Living Theatre signs are still outside, but inside there is nothing but gathering dust: an empty lobby, an empty auditorium, an empty stage.

Meanwhile, the World’s Fair flourishes. The subsidized Repertory Theatre of Lincoln Center has reduced its repertory to one production, Arthur Miller’s pretentious After the Fall, which persists not because anybody likes or respects it but because thousands of Life readers want a peep at Miller’s vision of the late Marilyn Monroe. The Broadway theatre is not so nearly dead that the second-rate Funny Girl can’t look forward to a profit of over eight million dollars.

The Living Theatre was closed in October. Under the banner of Exile Productions, organized for that purpose, The Brig was revived during the winter at the Midway Theatre, which was lent to the Becks by Irving Maidman. The revival never showed a profit—but it enabled the acting company to develop enormously. By the end of the two-month run at the Midway, the actors were continually trading roles, often playing a different character at each performance, and had achieved a remarkable esprit that survived the subsequent months of inaction. The Living Theatre’s principal weakness over several seasons had been its acting, which was always uneven and sometimes bad. But during The Brig the actors developed a clarity and directness of style which fulfilled the production concept. Whether this gain can be applied to other works is yet to be seen; rehearsals were imminent for a new production when the theatre was closed last fall, and since then no new work has been possible. But the Becks plan to put a new production of Brecht’s Antigone, translated by Judith Malina, into rehearsal immediately after the London opening.

In January the Becks were indicted by a Federal grand jury on eleven counts of “impeding a Federal officer in the pursuit of his duties.” The indictment carried a maximum penalty of 31 years in jail and $46,000 in fines. The charges had nothing to do with the non-payment of taxes, a fact that confused both press and public (and possibly also the jury) during ensuing months. The crimes specified in the indictment all occurred during that one October weekend, when the Becks refused to leave their theatre and staged a “play-in” of The Brig. After the Federal agents had come in and tagged everything as government property, Julian broke the seal on Judith’s dressing room door in order to get a sanitary napkin; a tagged mimeograph machine was used to run off a few more copies of a press release giving the background of the situation; Julian sat down on the stairs to prevent agents from removing a cabinet containing personal files; a tagged sewing machine was used to repair a costume. The Becks admitted all these acts during the trial, attempting to demonstrated that none of them had impeded the IRS in the execution of its legitimate duties and further showing that the sewing machine and mimeograph machine weren’t Living Theatre property and were therefore not seizable. Other accusations were denied, such as the allegation that Judith had cried “Storm the barricades!” out the window of the theatre, thus inciting others to join the resistance.

To many the grand jury indictment seemed excessive and, in some of its details, ridiculous. The government had chosen to prosecute the Becks to the full extent of the law, giving no consideration to the emotional situation at the time of the closing or to the obviously non-criminal motivations behind the various actions. Crime is crime, the indictment seemed to be saying. Julian commented: “We are surprised and shocked that the grand jury was not able to differentiate between the devotion of artists to their art and criminal acts.”

All through the spring the wheels of justice ground on, in a series of hearings and postponements and delays. During this time a committee of friends of the Living Theatre attempted to rally support among other professionals, and the basic misunderstandings became evident. Again and again the question was asked: why shouldn’t the Becks have to pay taxes just like everybody else? But that had never been the issue. The Becks failed to pay their taxes because they had no money. And, in fact, they had paid large amounts of taxes, more than $60,000 in taxes in the period in which they had accumulated the $28,500 delinquency. They were eager to pay their taxes. They admitted their delinquency. The case had nothing to do with taxes.

Sometime during the spring Judith and Julian decided to act as their own defense lawyers in the trial. Almost everybody told them they were crazy, that they would lose; but again, that wasn’t the issue. They felt, the more they thought about it, that a lawyer would concentrate solely on getting them off, that a lawyer would do anything he could think of to prevent a conviction and keep them out of jail. But the Becks were determined to confront the government, not on its terms, but on their own. Believing themselves to be innocent, they wanted to present the facts openly to a jury and let the truth make them free. Hiring a lawyer to apologize for them would be a tacit admission that innocence is not enough, that their country’s judicial system does not warrant their trust, and that it is not possible for the individual citizen to choose the spirit of justice over the spirit of the law. They had too often witnessed the standard American courtroom performnce, in which opposing attorneys and the judge play an obscure and antic game while the defendant sits by helpless. And, although their optimism proved unwarranted, they went to defeat uncompromised.

The trial, which began in mid-May, was punctuated with dramatic incidents. (Judith referred to it as a “legal happening.”) Supporters of the Becks turned out in numbers and made their sympathies evident. The Becks themselves were arrested one day on their way to court when they paused and posed for pictures and allegedly clogged the block-long steps of the courthouse; the prosecutor himself, United States Attorney Peter K. Leisure, came out and, in a maneuver of obscure legality, attempted to unarrest them; and finally the situation was saved by Yack and Licht, police officers who arrived on the scene and, informed that judge and jury were waiting within, dismissed the charges.

But all that was gravy. The trial itself was proceeding on several levels at once, with an evident lack of mutual understanding. The Becks felt that all they had to do was communicate the truth to the jury, but they found that the truth was more complicated than they had imagined, and infinitely more difficult to communicate to these 12 strangers. And after eight days of testimony the issues had still not been clarified. Point by point the Becks attempted to refute the charges, to demonstrate either that they had not done what they were accused of or that the act had in fact not constituted interference with the duties of the IRS officers, but the confusion grew only thicker; the methodological details of the law are alien to the Becks’ way of thinking. And in the end they made a plea to the jury essentially on humanistic grounds.

From Julian’s summation:

“When Judith and I decided to defend ourselves, we said to you right at the begnning, it is because we don’t want to put our case on the technical parts of the law… We thought: we know what we did, and we will take the responsibility for it. And, yes, they said to us, ‘Will you waive a jury?’ And we said, ‘No. Let some people come in. Let twelve people come in who are a part of this New York City that we live in and let them look at what we have been doing and they will give us the answer.’ Because we have said it again and again and again, our work is not for some small coterie of artists who are interested in some esoterc thing. We have dreamed again and again and again of bringing our work to everybody, of bringing our work to artists, to people who are in business, to men and women in all walks of life. We want to speak to them, we want to tell them directly what we are all about, and we wanted to tell you as best we could what the plain facts were…

“We brought our case before you because we have a belief in certain human values, and we feel that if we can’t live our lives face to face with each other, talking to each other—and we have got to try to communicate, we have to get through to each other, because we are dying of islation, all of us, and the pain of loneliness and our inability to talk to each other and to know how to talk to each other—we have to get through and this has been our attempt to get through to you, to twelve perfect strangers, who showed from the beginning no interest, absolutely no interest in our work.

“You are not some people we met in the lobby of the theatre. You are to us total strangers, and we are trying to set up with you, as it were, a dialogue, and to tell you what we are all about. And we are telling—we are asking you to ask yourselves all the questions and then to decide to what extent we violated the law and to what extent we violated human law and to what extent we upheld certain other very sacred laws and then you have to say: If you decide that they did try to do something that they consider sacred, did they succeed or did they fail? And if they succeeded you will say they are innocent. And if they failed in trying to uphold a certain kind of law that they thought was sacred, then are they guilty?”

From Judith’s summation:

“In what happened at the Living Theatre… we found ourselves—a group of artists—confronting the law, confronting not only the law but the rigidity of the law, and in many ways we didn’t believe it was going to be that rigid. You have heard us say that we could not believe that what we were doing was a heinous wrong. You have heard us say that we believed that what we did was right and good. But the law’s nature is to be rigid and to define, and then it is up to the human heart, which is not rigid unless it is dead.

“If our intentions were what they say they were, if we have not lied to you, then surely the rigid line of the law has to here be examined by the giving, yielding human emotion that prompted it and that prompts us all in our daily actions and in our daily lives… If the law is so rigid that it cannot allow for right action, then it becomes a tyranny. A law that is just must also include in the mercy which it entails that area in which one can overstep it for good and just cause and, above all, wth good and honorable intent. If it cannot, it will atrophy and become something else…

“The Germany in which my father was brought up was a free country but it changed its nature, it changed its laws, and the laws became more and more rigid and the laws no longer left room, and when the Gestapo suddenly seized and closed all the Masonic lodges in Germany very early in the Hitler regime, there was no protest and there was no outcry. It was merely the closing of an institution under the law. It was under the law. I am not suggesting that we have come to such a terrible pass. Pray to God that we never shall. But the rigidity of the law and the unwillingness of the law to change and yield to human feeling, this seems to me the crucial point at which tyranny begins.

“When those who say, at this point the law is wrong, can no longer say it, and peaceably act upon it, when we come to that point when a person can no longer say, ‘I am an anarchist, I believe in the peaceable overthrow of the government, I believe in a law of love, and I believe that the laws of love could be sufficient to organize human life in a beautiful and meaningful way without punishment and harm, as long as I can say that, I am living in a free land. And when I can’t say it any more and still be free to speak of it and advocate it, then I am no longer living in a free land.

“And I have the faith that you people, realizing what we did that night in that theatre, will realize that the rigidity of the law in regard to our actions is here in conflict with a tremendous human passion and human emotion. What had just happened to us? We had just lost our life’s work, our whole life’s work, a life’s work begun when we were children in school…

“We told you about how we had built that theatre, how the stage that I was carried off from that night I had nailed together with my own hands. When we speak of building that theatre ourselves, I don’t mean that we cooperated with a contractor. We did the work and we loved the work, and here it was gone, and here it was over.

“We were in mourning for our theatre, and we were in shock, and we decided to say, ‘No, don’t take it away from us. We love it.’ We were saying no to the rigid letter of the law and yet trying at every point to do no harm, and we still don’t see how putting on that performance that Saturday night really hurt anybody except the pride of the rigidity of the law.

“The law is proud of its rigidity. And the feelingful and merciful side of the law—they say the pillars of the temple are made up of the two pillars, justic and mercy—and the merciful side of the law is that side which gives the leeway to interpret a good act as not a crime when it is not a crime. And I appeal to you to understand that we do not believe that we committed a crime, that we never intended to commit a crime, and I hope you will find from the facts and the evidence, as you examine them, that we did not.”

The jury found them guilty. In his charges to the jury the judge, the Honorable Edmund L. Palmieri, astonished the Becks by emphasizing technicalities, instructing the jury, in effect, that its task was not to determine whether the defendants had been right in what they did but whether they had violated the law. “If you should find that the law was violated as charged,” he told them, “you should not hesitate because of sympathy or emotion to render a verdict of guilty as a clear warning that a crime of this nature may not be committed with impunity.”

When the verdict was announced, the trial developed into a genuinely dramatic improvisation. The judge’s courtesy and helpfulness had disposed the Becks to expect his help, not this further strictness. And they felt that their summations, in which they had spoken as openly and persuasively as they knew how, could not fail to move the jury. And yet they were found guilty, Julian on seven counts (maximum sentence: 19 years and $26,000) and Judith on three (eight years, $10,500). They were stunned, and they reacted aloud. The following dialogue blossomed between them, the prosecutor Peter Leisure, and the judge.

MR. LEISURE: Your Honor, the defendants now stand before you, Julian Beck, convicted of—

MRS. BECK (quietly, almost involuntarily): Innocent.

MR. LEISURE: —seven counts and can receive a maximum of 19 years in jail on the counts he was convicted of. Judith—

MRS. BECK (louder): Innocent.

MR. LEISURE: Judith Malina Beck stands convicted and can receive a maximum of—

MRS. BECK (louder): Innocent.

THE COURT: Please, Mrs. Beck, please. You must stop this.

MRS. BECK: I may assert my innocence at any time in my life. There is no time in which I can’t assert my innocence. I am an innocent person. I am innocent. No one can stop me. You will have to cut out my tongue if you wish to stop me. If you want to cut out my tongue, you can stop me. I do not give you that privilege, sir.

THE COURT: Mrs. Beck, you must respect the proceedings of the court.

MRS. BECK: I can’t. I have taken it for ten days and I have respected a terrible travesty of justice. I have watched the majesty of the United States degraded and demeaned by trivia that is beyond belief. I have seen the law of this country lose all of its dignity and it is shocking to any thinking person and, I presume, your Honor to say that there has not been real thinking.

THE COURT: (inaudible)

MRS BECK: The horror that has been handed down here is such a disgrace to this country that the moves I will have to take in order to vindicate this country’s honor are such that I fear I cannot possibily grant this country any more privileges on my behalf. Don’t touch me, I will go limp on you.

THE COURT: Your conduct is disrespectful.

MR. BECK: I move, your Honor, at this point to set aside the verdict of guilty as contrary to the evidence.

THE COURT: I find you both guilty of contempt in the presence of the Court…

MR. BECK: My request is for immediate sentence.

MRS. BECK: I would like to be sentenced now. We have suffered for months.

MR. BECK: You know as much about us as—

MRS. BECK: There is no crime in our innocence and honor.

MR. BECK: You know as much about us, your Honor, as we have ever known. We have laid ourselves bare and told you all the facts of our lives.

THE COURT: I cannot do it immediately. I do not think it is a good thing to do.

MRS. BECK: Because it is unbearable to stand another ten minutes without knowing what is in your hard heart.

THE COURT: I can tell you this, Mrs. Beck. I have no intention of sending you to jail, and so I have told you that throughout this trial in order to calm you. You have known it, and I am sorry I now have to repeat it. I have told you repeatedly that I had no intention of sending you to jail if you were convicted, but you apparently insist on playing some sort of dramatic role and making me or other people think that you are threatened with a long period of jail and you know that that threat has not been hanging over your head.

Neither Judith nor Julian could remember the judge’s having made such a promise; but in the light of these remarks, they were more than surprised when, at the sentencing on June 5, they both received prison sentences—Judith for 30 days and Julian for 60. The technicalities of the sentences were curious. The judge emphasized that they were being punished for contempt of court as well as for the original crimes. Identical sentences were set for both charges to run concurrently, leading to speculation that they might have received suspended sentences had it not been for the outburst which led the judge to hold them in contempt.

Between the pronouncement of the verdict and the sentencing, the Becks were subjected to an interview with a parole officer. Among other things, he asked them if they had had premarital sex. He also indicated that they would be expected to follow his moral precepts during the probation period, which the judge set at five years. Their probation will be unsupervised during this period, but they can be jailed for violation of any state or federal penal law, which raises the stakes if they should want to participate in further peace demonstrations.

In a pre-sentencing statement to the judge, Judith referred to the Boston Tea Party as a classic American example of heroic civil disobedience in the cause of justice. If such acts are no longer possible in this country, she said, then the history books should be rewritten.

Judge Palmieri, in sentencing, described the Becks’ actions in resisting the theatre closing as “challenges to a test of power with the government.” He said, “The government cannot accept repudiation of its authority… Our society is based on civil obedience.”

After the sentencing, the Becks announced their intention to appeal the convictions. The judge denied Peter Leisure’s request that the defendants be immediately jailed and released them on bail pending the appeal. He set broad limits on the bail bond in order to permit the Living Theatre to fulfill its European obligations.

Julian explained later that the real issues of the case had never been confronted. “The significance of this case is the question of whether passive resistance constitutes forces,” he explained, and it is on this basis that the appeal will be pursued. He is confident of winning a reversal. The law they stand convicted of having broken reads: “… corruptly or by force or threat of force did impede a Federal officer in the administration of his duty.” Later in the statute the phrase “threat of force” is defined as “threats of bodily harm.” There seems no question that the Becks were not “corrupt” in their actions—although several Federal men insisted through thick and thin that the Becks were mainly interested in fame and money just like everybody else. As for the issue of force, they and their followers are passionately committed to a philosophy of non-violence. (Thus Judith took particular exception to Peter Leisure’s description of their behavior: “The law is contrary to their personal views so they disobeyed it violently.”) For the jury, however, the judge defined force as “obstructing physical movements.” The discrepancy between this interpretation and the wording of the law itself will probably be the basis of the appeal, which has the support of the American Civil Liberties Union.

In addition, there is in the law on seizure a provision that Federal officers must exempt $250 worth of the tools of the trade, thus not depriving people of their ability to continue working. This provision was overlooked by the Federal officers, and the Becks claim that the seizure was therefore illegal. If the seizure was illegal, then the testimony of the Federal officers becomes inadmissible (it is “the fruit of an illegal seizure”), and the Becks’ resistance is justified. “We didn’t get our legal arguments across,” says Julian, “because we were not lawyers and they didn’t take us seriously.” As for the contempt charge, Judith says, “They are putting us in jail for having an emotional outburst instead of accepting with decorum and quiet humility the decision of the court.”

Meanwhile the United States is the poorer for having no Living Theatre. Edmund Wilson wrote recently: “Our country has become today a huge blundering power unit controlled more and more by bureaucracies whose rule is making it more and more difficult to carry on the tradition of American individualism.” As it turns out, the only way the Becks can continue as American individuals is by going abroad. They are ambassadors we should be proud of, but when they come home they will be jailed as criminals.