Directing: Samuel Beckett

“KRAPP’S LAST TAPE”

Taos Theatre Company, Taos Plaza Theatre, Taos, New Mexico, 1978; Lit Moon World Theatre Festival, Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, 2002

Once we had settled down in Taos I called up Bill Bolender, an actor and founder of the Taos Theatre Company, introduced myself, and said I would be interested in working with him. He came right over, and we hit it off immediately. We had the idea of doing a play in the movie theatre on Taos Plaza, a smallish theatre with a raked auditorium and a shallow stage in front of the screen, and Bill Whaley, the owner was receptive. I have tremendous admiration and love for the plays of Samuel Beckett, and a double bill of “Krapp’s Last Tape” and Edward Albee‘s “The Zoo Story,” with which it had been paired in New York, seemed appealingly doable. Neither play requires much space, Beckett’s Krapp was a wonderful role for Bolender, and he could perform “The Zoo Story,” a two-character one-act, with his partner, Steve Parks, another good actor. I was eager to direct these plays and actors, and the production was quite successful. Taos is a unique town, isolated at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo range, largely Spanish and Indians, but the small minority of Anglos eagerly turn out for interesting cultural manifestations.

The Beckett-Albee double bill having established my credibility, Bill Whaley asked me to direct a production of “West Side Story,” which he produced at the Taos Community Auditorium. Bill Bolender and Steve Parks wanted me to direct all their productions. But with two little boys at home it was too much for me to be gone every night, and after “West Side Story” Michele asked me to take some time off. As a result I only did one more production with the Taos Theatre Company, “Life Is Dream,” before we packed up and went back east.

I had a second opportunity to direct “Krapp’s Last Tape” in Santa Barbara in 2002, which I enjoyed even more. My friend D. J. Palladino commissioned it (not to suggest by the word that any money changed hands) for his 50th birthday party at Center Stage Theater. D. J. put me together with the actor Robert Lesser, whom I had admired in various performances at Ensemble Theatre Company, and we had a glorious time working on this exquisite play. We read biographies of Beckett, which made me like and respect the man even more, and we worked through the text with the closest attention. Bob is a meticulous craftsman, and we were mature enough to appreciate how much is at stake in this cunningly wrought play. It is a kind of duet between the solo actor and his own earlier recorded voice, which he plays back to himself and responds to. This involved a second tape recorder in the wings, which was wired to play out of the speakers of the antique tape recorder on stage, and I had the pleasure of operating it, coordinating the sound cues as Bob played different tapes, rewound and repeated sections, etc. Once we had the production together, it seemed silly not to do it more than once, and I arranged for us to play it as part of John Blondell’s Lit Moon World Theatre Festival, where it was well received. It was a matchless pleasure to work with such a fine actor on such a beautiful text.

Reviews

from The Taos News

by John Nichols

Last year, when I saw “On the Waterfront” for the first time in almost twenty years, I came out of it feeling that I had outgrown the film and its simplistic message-realism. Yet I had drawn as much, if not more pleasure from it, than I had as a teenager, because of the wonderful performances of Brando, Malden, Steiger, Cobb, and Eva Marie Saint.

After last Saturday night’s performance of Samuel Beckett’s “Krapp’s Last Tape” and Edward Albee’s “The Zoo Story,” I left the Plaza Theatre feeling much the same way: the plays had been diminished by the passage of time, but they are still showcases for good actors, and Saturday night’s performances were superb.

Nobel Prize be damned, I am no fan of Samuel Beckett’s monotonous misery. And although I have enjoyed such Albee plays as “The American Dream,” his obsessive bourgeois angst, in plays like “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” and “The Zoo Story,” has always turned me off. Albee and Beckett in such veins are precursors of today’s Jerzy Kosinskis, Joan Didions, and Thomas McGuanes, intelligent and often beautiful writers whose dead-end art—the exquisitization of alienation—has always seemed precious, self-defeating, and fairly boring to me. Personally, I have other hopes for art.

This belligerent introduction is so readers will understand the kind of personal prejudices this reviewer takes into plays like “Krapp” and “Zoo Story.” Making it all the more interesting, I think, that I enjoyed both plays immensely.

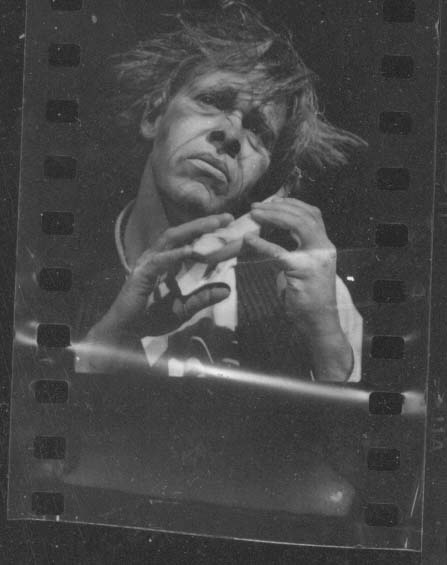

In “Krapp,” Bill Bolender was wonderful in a role which, on the surface, called for him to do little more than peel a banana and sit in a chair at a table listening to the voice of himself 30 years ago. But Bolender made you hold your breath from start to finish as you watched him listening, and reacting with a thousand subtle nuances of emotion, to the recorded memory of his strange life.

In fact, Bolender can act the pants off just about any character thrown his way. And on Saturday night, whether he was clowning obscenely with the sound of the word “spool,” or pathetically parroting his own young man’s laughter, or nearly having a coughing seizure while trying to sing a hymn, or taking a pratfall on a banana peel, or frowning broken-heartedly at the recollection of a long-ago love affair, Bolender was a special theatrical treat not to be missed.

And although he was also excellent as Peter in “The Zoo Story” (just the way he cleaned his glasses at the start, handled a handkerchief, and adjusted a book mark perfectly established his character), that play belonged to Steve Parks in the role of Jerry: he pulled off a remarkably sustained performance.

The play is simple enough: it borders on being hackneyed. Jerry the drifter, bum, boarding-house, family-less, strung-out (but sensitive) tough guy, runs into Peter the wived and daughtered and parakeeted family man who ears 30 Gs a year and believes that all’s well with the “civilized” world. And, in the course of their brief moment together at a park bench, Jerry blows the lid off Peter’s complacency in such a way that Peter is finally goaded into executing Jerry with the drifter’s own knife, which is what Jerry had in mind from the start.

The play is pretty much a non-stop monologue for Jerry, and Parks built up to the moment of his own murder-suicide with tremendous skill. There was nary a false step in his language, or in his moves about the stage, or in his timing, or in his hysterical dying scene.

Admittedly, I haven’t gone to a whole lot of plays in Taos, but Parks’s “Zoo Story” tour-de-force Saturday night is the best acting that I’ve yet experienced here. The most recent thing I’ve seen to which I can compare his fine performance is the role of Martin Dysart in “Equus,” a play with striking emotional-thematic similarities to “Zoo Story,” that I saw recently in Los Angeles, and in which Anthony Hopkins starred.

Parks is no Anthony Hopkins, but in a way his acting in this small intense play seemed every bit as controlled, given the reduced frame of reference, as the Hopkins performance in Los Angeles. Jerryanic crippled vitality made the audience uneasy from the start, drawing us inexorably toward the final horror with a captivating fatalistic surge. Parks’s entrance onto the stage was like hanging that fabled gun on the wall: we knew it was going to be used, and not for a moment did Parks let us off the hook by releasing us from the fear engendered by that knowledge.

That the plays worked as well as they did must be attributable to Michael Smith’s gutsy direction. One small example: the tension and alienation-drama of the plays was heightened by placing the focal points of both works—a desk in “Krapp,” a park bench in “Zoo Story”—so that they were facing directly toward the onlookers. In “Zoo Story” this meant that Jerry started out addressing Peter with his own back turned towad much of the audience, a ploy that immediately created tension both on and off stage, and heightened the themes of human cruelty and indifference. It takes plenty of hutzpah and skill not only to try such a device, but to pull it off as well.

And both plays succeeded in a smoothly synchronized way that indicated real professionals were at work.

A final word: Bill Whaley is to be commended for opening the Plaza Theatre to this kind of effort. His willingness to support the local arts, his determined effort to make the TAA Theater vital, and to sponsor projects that are thought-provioking as well as entertaining, has helped enormously to create a truly upbeat arts scene in Taos.