Directing: “West Side Story”

Taos Community Auditorium, Taos, New Mexico, 1978

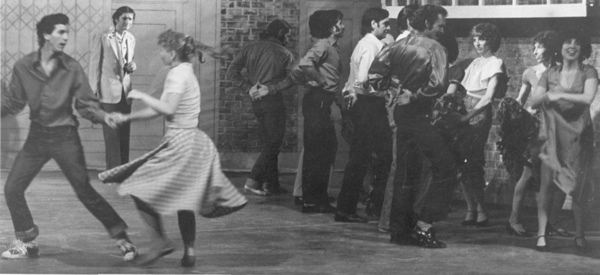

What drew me into the theatre in the first place was seeing musicals in Kansas City when I was a child. I remember “Brigadoon” at the Municipal Auditorium and several classic operettas at the Starlight Theatre in Swope Park, which opened in 1950 with “Desert Song.” My parents went to New York once or twice a year—my father had business there—and my mother brought home sheet music of the Broadway musicals they saw and played it on the piano and sang. When I went east to school, I began going into the city and was taken to many musicals. When I actually got into the theatre, though, I found myself working in very modest situations and doing contemporary work of a very different character. So when Bill Whaley asked me to direct “West Side Story” at the Taos Community Auditorium, I was delighted. I did it in part as a personal tribute to Jerome Robbins, who had conceived, directed, and choreographed the original production, and whose theatrical flair and artistry had given me many thrills. (The set change into the dance at the gym was a direct imitation of an unforgettable moment in his “Funny Girl.”)

“West Side Story” was by far the biggest show I had directed, with a cast of more than thirty. Staging it was a team effort; thank God for the rest of the team! There were two choreographers, one for each of the gangs; an excellent music director, who took care of training the singers; not to mention an assistant director who despised me and made trouble (an echo of this crept into my play “Heavy Pockets,” which is set in Taos the following January). I relished the challenge of fulfilling the show’s considerable scenic demands with our limited facilities and budget and did the lighting myself, with eleven working dimmers. The cast was a cross-section of Taos’s marvelous diversity. We all worked hard, keeping ourselves healthy through the cruel winter with many grapefruits. John Nichols, the novelist, wrote a rave review in the Taos News, and the show was a tremendous success.

Reviews

from the Taos News, April 13, 1978

by John Nichols

Sound the trumpets! No hyperbole is too good for the current production of “West Side Story” at the Taos Community Auditorium! The play, like its heroine Maria at one point during her lightning romance with Tony, is 12 feet above the ground and soaring!

Nothing that came off as well as that play on its opening night Thursday could have succeeded on such a grand scale if it had not been for the fact that every last person involved was a real hero.

The sets by Kit Schuetze are imaginative, realistic, powerful; and they move on and off with split-second timing that is astounding. And without the exquisite lighting produced by some wizards backstage, songs such as the marriage vows sung by Bob Draper and Randy Raiser as Tony and Maria would have had but half the impact. And how Richard Crawley and Don Thompson’s orchestra and the stage players mastered so well a difficult score, and the timing of a treacherously complex choreography, is beyond me. But they sure did it up brown!

The opening rumble scene starts the wonderful choreography of Rory Duval and Tori Olds off with a bang. Much later, when the Jets, brilliantly led by Marco Perella as Riff and Peter Parks as Action, go into their jiving “Keep Cool” tune, there’s an astounding revelation: Dr. Robert Knudson (as Big Deal) can not only cure people during the day, but by night he can leap like Nijinsky! And here comes the clincher! Johnny MacArthur can actually dance! And sing! Even while standing in a garbage can!

The way everybody manipulates mood is special. There’s a lovely riff early where Perella and Draper are jiving together in a hip, delightful way; seconds later Draper launches into a powerful, yearning song, “Something’s Coming,” and he’s got a voice, and a delivery throughout, that can break your heart. And just as his last note dies away, somebody runs across the back of the stage drawing across a glittering line of cellophane strips, and presto! with a miraculous change of lighting, and the appearance of two dozen dancing actors—highlighted by the bip-bopping of Riff’s girl Velma (Irene Mokstad)—who just materialize out of thin air, we’re in a crowded dancehall. It must have taken real bravado for the leaders of this thing—led by director Michael Smith, his assistant Emily Regier, and all the others—to teach the actors how to leap from one radical mood to the next.

And the costumes of all those teenage punks! I wanted to shriek with nostalgic recognition! Costume designer Carol Kalom and her people get the Sha Na Na nostagic threads award for 1978!

But a miracle a minute is happening here. Staggering into the center of that dancehall, lo and behold it’s Bernard Wisser as Glad Hand, the hapless neighborhood idealistic social worker. Wisser literally brings down the house.

Enter the doomed lovers. Raiser and Draper perform a very gentle dancehall love riff, while Leighton Taylor, who plays Chino, Maria’s intended boyfriend, helplessly looks on.

The second the dancehall scene ends, the stagehands snap their fingers and an enormous fire-escape balcony on a tenement materializes, and Draper and Raiser pull of another of their passionate and touching moments. Raiser is so beautiful, so innocent, she projects her love, vitality, and hope so well: and has a magic voice to boot!

An instant scene change, and here are Oscar Lewis and Peggy Klaus (Bernardo, Anita) doing one of their sultry, sexual innuendo numbers together, and believe me, they can really do them. Lewis is sinuous, slick, macho, and brilliantly ghetto arrogant. Klause creates magic in her singing and dancing role as Anita; she’s fiery, provocative, tough—a real pro.

Then the Sharks’ women dance up a raucous storm while singing “America.” Ellen Seligman gets her change to shine here, and she’s positively brilliant as a hokey, sexy idealist in opposition to the spicy mockery of Ann Ferguson, Kiva Robnett, Virginia Padella, and Rachelle Smith.

Next, it turns out that nobody can spin a yo-yo on stage like the Jets’ Snowboy, played by Tui Wilshinsky, who slides in and out of mocking wiseguy ghetto riffs and gestures with remarkable ease.

Pretty soon Noelle Kalom (Baby John) is going to tire of hearing how good an actress she is. One stand-out moment is when she races about the stage in a helter-skelter panic like a terrified bird while everybody else is absorbed in the rumble.

And her dad, Ron Kalom (the crotchety despairing Doc), gets a real laugh and a real tear simultaneously when he sums up all the pathos and comedy by saying mockingly, in response to the delightful acerbity of Jonathan Gordon as the cynical Detective Schrank, “I have no mind, I’m the village idiot!”

As for Officer Krupke? The audience falls flat on its face with laughter as that dumb cop, played by La Cocina’s own Pat Enright, tumbles all over himself in what will long be remembered as one of the great Taos slapstick numbers. And it occurred right in the middle of a wonderful scene between Baby John and A-rab, played by Nellie Nugiel, who somehow comes off as about the funkiest gangland cornerboy on the Jets.

And what about Tim Dice (he plays the Jet Tiger), obnoxiously bouncing a rubber ball on his arm by flexing his muscles in the Jets’ complex “Gee, Officer Krupke” number? Now that’s the kind of arrogance that makes these hoodlums really bad!

Merilee Dannemann as Anybody’s, an awkward girl who wants to be a fighting member of the Jets, opens her acting wings and takes off: she’s tough, kooky, and sports one of the funniest and at the same time touching dance rhythms. One nifty moment is when she ends the Jets’ marvelous “Cool” song and dance by freezing all the Jets one by one, her finger pointed at them like a gun, as she shouts: “Pow, pow, pow!”

But nobody is going to freeze this play, because it’s not being carried by one or two or seven people, it’s being carried by everybody. As much by Sharks like Vito Trujillo and Jose Estrada and Francisco Guevara, whose presence maintains the theatrical illusion of one tough city gang, as by the actors and dancers like Perella and Parks, who seemingly can do no wrong in roles that require a lot of talking, a lot of singing, and a lot of hoofing.

And although the Sharks’ men and the Jet’s women do not have as large roles as the others, their superb coordination, timing, and dancing hold the play together. Hence people like Dennis Olonia, Janet Aspers, Samuel Torres, Jane Burke, Mimi Trujillo, Linda Trujillo, Barbara Goldman, Cindy Rea Daniell, and Darcy Owen—these dancer-actors, by their ability to keep the play flowing, to emote with their faces and their bodies, weave it into a whole experience, a truly dramatic vehicle that jells.

As I was leaving the TAA theater Thursday, a playgoer in front of me said, “I expected to have a good time tonight, but I sure didn’t think it would be this good.”