Short Plays

“MORE. MORE. I WANT MORE!”

La Mama, New York, November 3, 1965; The Changing Scene, Denver, September 1968; Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, September 2007

I wrote this tiny play with Remy Charlip and Johnny Dodd for our friend Joyce Aaron to perform on an evening of short plays organized by Robert Patrick as a benefit for La Mama. Robert Breuler directed it at The Changing Scene in 1968 on a program including Beckett’s “Act Without Words I,” “Vorspiel nach Marienstein” (see below) and “Vietnamese Wedding” by Irene Fornes. I revived it as part of “Bad Dogs and Other Plays” (see “Bad Dog”), with Susan Keller giving an artful performance as the two-sided protagonist.

“MORE. MORE. I WANT MORE!”

a conversation with herself for Joyce Aaron

by Remy Charlip, Johnny Dodd, and Michael Smith

Set: a table, two chairs, two cups of coffee, two napkins, and two spoons; or nothing.

Joyce skips on.

GIRLISH: Do you think I should be zippy and zip around like a little dog?

WOMANLY: Well what do you want?

GIRLISH: More. More. I want more!

WOMANLY: Well you’re old enough, you should know how to get what you want.

GIRLISH: But everybody expects me to be zippy.

WOMANLY: Well you are zippy.

GIRLISH: What’s the matter with that?

WOMANLY: Well, but is it what you want?

GIRLISH: Sure, there’s nothing wrong with that.

WOMANLY: Well I could answer that question.

GIRLISH: What question?

WOMANLY: Well the first one you asked. Do I think you should be zippy and zip around like a little dog? I think you should be zippy if you want to be zippy but I think you should do something else too.

GIRLISH: What?

WOMANLY: Well what do you want me to tell you? Do you think I’m happy myself?

GIRLISH: Well, you’re sophisticated and mature and relaxed and you do a lot of interesting things.

WOMANLY: I’m so unzippy I can’t even work myself up.

GIRLISH: Well what is it that people always say when they want to have sex?

WOMANLY: Why don’t we go up to your place and have a cup of coffee?

She acknowledges a nod and walks off.

“TONY”

La Mama, New York, 1971

This monologue was inspired by my friend Paul Sand’s winning a well-deserved Tony award for his performance in “Story Theatre,” and Lucy Silvay performed it on a double bill with “A Dog’s Love” at La Mama. It was written for a man but works equally well with a woman: Lucy was stunning in it. That May I arranged for her to perform it as entertainment at the Obie Awards: I was no longer running the Obies and feeling rather sour-grapes about them. Unfortunately a friend of mine had come to town earlier in the day with a shopping bag full of the strongest marijuana yet seen; Lucy got too high, and Ross Wetzsteon stopped the performance in the middle. I was not there but it must have been awkward. Edward Barton, who appeared as the beach boy in “A Dog’s Love,” later learned “Tony” and performed it a few times. He too was dragged from the stage at least once. The play is obviously meant to be abrasive but not that abrasive.

“TONY”

(for Paul Sand)

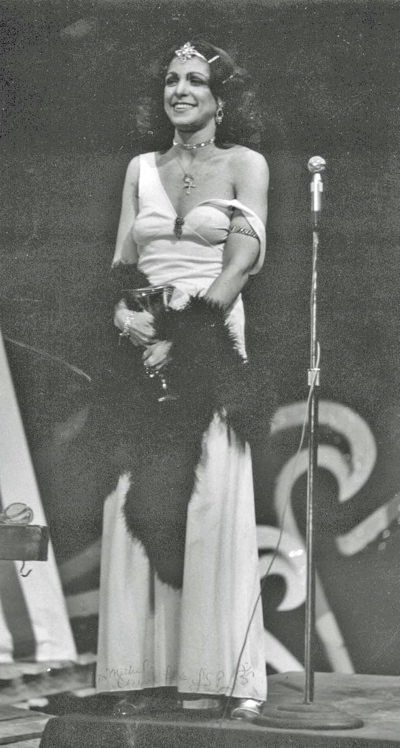

Wild applause. Super-up Broadway-type music. Dazzling lights. A spotlight catches TONY coming up the aisle out of the audience. He whirls around, in a state of ecstasy, and comes up onto the stage. A microphone on a stand down center. Maybe a glittering curtain upstage. A beautiful woman in a silver sequin dress smiling warmly and professionally hands him a large silver cup, then steps back and leaves the stage. The lights are so bright and zeroed in that he can hardly be seen. TONY is young, unbelievably handsome, sublimely glamorous, dressed ultra-elegantly in highest fashion, with sparkling studs. He wears red glasses. He is thrilled and radiant. This is the high moment of his life. He is flashing as though he had taken some far-out drug. Television cameras are transmitting his image planetwide. He speaks into the mike, which amplifies his voice and adds echo as though he were in an enormous hall.

TONY: I’ve never been too sure about reality. (Applause, laughter; then the crowd quiets.) But this is—this is the greatest moment of my life, and I’m very happy to share it with you and some of the people who made it possible. First I want to thank my mother. I know I’ve been unbearable but she bore me. She couldn’t be here tonight—after all, I didn’t know I was going to _win_—but she’s watching right now, sitting there in her trailer in San Rafael with her girlfriend Gladys. (Very intimate, into camera.) Hi, Mom, I really miss you. How’s it going, Gladys? (To audience.) Gladys had her leg blown off in a munitions factory in ‘43, just a few months before I was born. I used to image that I was that leg, you know, reborn, reincarnated. I guess I’m really making it up the ladder to whatchamacallit, bliss, you know, over the top. Just think of it, Gladys’s leg up her in front of— I bet she’d give her other leg to be here now, out there in the audience, sitting there in the aisle in her wheelchair, stumps jumping to the music. That would make me twins, I guess they’d have to give me two cups. Aw gosh, one of me would say, I don’t deserve this. You’re right, says the other, I better take them both. And he splits, leaving me alone up here. I don’t know what to say. (Looks around in confusion, takes glasses off, looks at audience, smiles, shields his eyes, squints, puts on his glasses.) Am I on television? What am I supposed to do? (Intensely, “acting.”) Gladys, Gladys, don’t you know I’ve loved you always, always hoped you’d have me over, let me come close to you, closer, let me touch the leg that still remains, my twin, my nonexistent holy half. Oh God! To be whole! Two-legged, two-bodied—four legs for only two! Instead of hopping through life this way. (Intent.) Gladys, I mean it, send me your leg my brother. (He nearly swoons.) Oh! Oh I’m so excited I don’t know who I am. (Peering closely at the cup.) Did I thank everyone? I can’t remember. Gladys, I did thank you, didn’t I? Gladys taught me everything she knew, which wasn’t much, but she was the only one, until I came to New York. A person like that leaves a mark on you. (Undoes tie, opens collar, shows invisible mark on neck.) Could I have a closeup right? Right on my neck. Right. O.K., just hold it there and I’ll work with it. Could I have a mirror? (Looks offstage.) I need a mirror out here. (To audience.) Gladys moved in with us when she came out of the hospital. I was a little baby, I didn’t have anything to say about it. I stayed in my room looking at myself in the mirror, listening to her and my mom talking in the other room and Daddy slamming doors. My daddy would go through the house slamming all the doors. The ones that were closed he’d open and slam. That was the only time I saw him, when he’d open my door and slam it. At first I’d put on my pants when I heard him coming. But he didn’t even know who I was, he just wanted the doors shut. Oh Gladys! I wish you were here, I’d let you jerk me off! That would be so nice! Isn’t this a pretty cup? (Winces or twitches on every “slam.”) After he’d slammed all the doors he’d go out the front door and slam it and get in the car and slam the car door and drive off and we wouldn’t see him again till the next day or the next year. (Rubbing his crotch.) As soon as he was gone Gladys would come hopping in. She had crutches but preferred to hop. She got so she could do it without a sound, and she could open and close the door without a sound. I could hear my mom still talking to her. My mom isn’t blind, exactly, she’s the opposite of blind, she sees things extra, like Gladys sitting there in the breakfast nook when actually she was in my room with me. I didn’t have any light in that room after Daddy broke the mirror. I was saving myself for this moment. But I could hear her when she breathed through her nose. She had a little tiny nose. Still has. I felt it. Gladys, thank you. Thank you, Gladys. Thank you, Gladys. Thank you, Gladys. Thank you, Gladys. Thank you, Gladys! And then SLAM! (Maybe he was about to come. He winces so violently that he trips and falls. He looks quite disheveled. He sits on the floor. In a small voice, off mike. A) Hello, Daddy. (Aside, in a fierce whisper; then alternating. B) Gladys, stop it! (A) No, no light! (Panting, shielding eyes.) Leave it off, it hurts my eyes! (B) No, don’t Gladys! (A) It hurt my eyes. (B) Stop! (A) I like the dark, it lets me think. (B) Shh! Be quiet! Slowly. (A; slowly) I think about the universe, about the stars, and galaxies, and atoms whirling in the molecules. (B) Yes, I like that. I like that. (A) I look at the worlds in crystals, in a worm’s brain, in flames, in space, worlds within and worlds without, worlds of worlds all whirling through time. (B) Yes, Gladys, good, that’s good, yes, good. (A) In my mind! Here, Father, I see them in my mind. (B; a gentle climax.) Oh, Gladys, Gladys, Gladys. Gladys. G-l-a-d-y-s. I am very smart and very wise. (A) Yes, Daddy, I won the prize. (Holds up cup.) You can feel it, here. Feel it? Cold and shiny silver, doesn’t it feel good. No, don’t take it. (Struggling as if someone were pulling the cup away from him.) Feel it but don’t take it! Ouch! (His arm is being twisted.) Oh, all right! (He lets go of the cup, which clatters to the floor. He stands, comes to microphone.) Is that enough? (Looks at cup on floor, pokes it with his toe. Into mike.) Thank you. (Smiles.) I love it.

(Blackout.)

“POINT BLANK”

David Brainard, Alfred St. John Smith, Laurel Lyle, Tom Petra, Susan Keller, Melissa Rose Ziemer, Melissa Paper, and Suzanne Bodine in “Point Blank”

Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, 2007

Written in my woodshed at Charlemont in June 1972 (the characters and tone overlap with my Denver Trilogy), this little experimental play waited 35 years to be performed. I took a chance and made it the centerpiece of “Bad Dog and Other Plays” (see “Bad Dog”).

Production Credits

“Point Blank” was presented, as part of “Bad Dogs and Other Plays,” by Re-Genesis (in association with Genesis West) at Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, September 14-22, 2007. It was directed by Michael Smith with the following cast and crew:

| GRANNIE | Suzanne Bodine | ||

| SON | Alfred St. John Smith | ||

| MARGE | Melissa Rose Ziemer | ||

| SANDY | Susan Keller | ||

| FRANK | Tom Petra | ||

| MOTHER | Laurel Lyle | ||

| DAUGHTER | Melissa Paper | ||

| FATHER | David M. Brainard |

| Costume Design | Mary Gibson | |

| Lighting Design | Michael Smith | |

| Stage Manager | Angelica Diaz |

“POINT BLANK”

This is a loop play. Begin anywhere, repeat several times, stop anywhere.

MOTHER: We’re waiting.

SON (enters): Don’t wait for me.

MOTHER: No, I know.

DAUGHTER: I’ve been ready for fifteen minutes.

MOTHER: Then who is it?

FATHER (enters): Am I in this? I’ll get the car started.

SON: Wait, I want to talk to you.

GRANNIE (enters): I can’t find my scarf.

MOTHER: I have it, Mother.

DAUGHTER: Shall I take my coat off?

FATHER: Well, what is it?

SON: Not here.

MOTHER: Oh go ahead, nobody’s listening.

SON: It’s not about anything.

SANDY (enters): Billy, you carry this big basket, weighs a ton, and there’s another box of stuff on the kitchen table, if anyone’s interested.

DAUGHTER: I’ll get it.

FATHER: And cheer up.

SANDY: There’s a lot of us.

FRANK (enters): Well, everything’s in. I thought you wanted to leave early.

SON: It’s just the attitude.

DAUGHTER: …like butter has knives…

SON: Oh shut up.

MOTHER: …and fingers have nails.

DAUGHTER: That’s not the point.

FATHER: Point blank.

MOTHER: I give up.

GRANNIE: Don’t give me that.

SON: Don’t look at me like that.

FRANK: Cut it out, all of you.

MARGE (enters): I thought I was late but everybody else is early.

FRANK: Where have you been?

MARGE: Waiting in the wings.

FRANK: Let’s fly right out of here.

MARGE: Not till I do something.

DAUGHTER: Margie, where have you been?!

MARGE: Waiting in the… hall.

DAUGHTER: Didn’t you look in the mirror?

MARGE: Why? What?… (Exit)

SON: One down.

FATHER: Well?

SON: I’m just a little hysterical.

MARGE (enters): I look fine

MOTHER: Of course you do.

GRANNIE: I’m not going. I have a bad feeling about this picnic, just like I did before the one in 1949 when that terrible news came over the radio.

FATHER: Well, the picnic didn’t have anything to do with it.

MOTHER: You don’t know that.

(Pause)

GRANNIE: Well, I’m not going.

DAUGHTER (taking her coat off): Neither am I.

FRANK: Don’t take it out on me.

FATHER: I know what you mean.

SON: How do you stand it?

FATHER: I’d like to sit down.

GRANNIE: Hasty butterfly of June/ Do not waste your pretty wings/ Believe the silver light of moon/ Not burning words a lover sings…

DAUGHTER: Why don’t you play something and we’ll all sing.

MOTHER: Not on your life. Put your coat back on.

SON (looking in basket): Would anyone like a deviled egg?

SANDY: Give me that. (Takes basket and leaves)

FRANK: I’ll help you. (Follows her out)

MARGE: What’s happening?

FATHER: Come on, let’s go.

DAUGHTER: We’re going to stay here and drink gin.

GRANNIE: And play gin.

MOTHER: Where’s Alex?

FATHER: Who?

MARGE: I’d like a martini.

(FRANK enters with a tray of martinis and passes them around.)

(SANDY crosses through without saying anything.)

SON: This reminds me of a play by…

FRANK: You’re not the only one.

SON: Yes I am.

FRANK: Have it your own way.

SON: I did until she came along.

FRANK: Excuse me, I have to keep passing the martinis.

SANDY (enters with cardboard box): Did you make one for me?

FRANK: I made one for everyone. I mean I made eight for all eight or however many there are.

SANDY: I only want three.

MOTHER: I’ll take the rest if there aren’t enough to go around.

FRANK: I’ll come around again with the empties.

MOTHER: That sounds just like Alex.

FATHER: Who?

SON: Where is he?

DAUGHTER: I guess he’s not coming. Or going.

SON: Are you?

DAUGHTER (putting on her coat): I’m not staying here.

SON: Then I will.

GRANNIE: I don’t need any company. I mean I wouldn’t if I were staying. Frankly I’d rather play solitaire. I’d rather drink gin than play it. We’ll cross that bridge when the cards are on the table. I’ve decided to go after all.

SON: Power to the animals!

FRANK (coming around with the tray): That’s what I say.

SON: I thought you said you’re not the only son.

FRANK: I’m not. You know my brother. He’s not either.

SON: But I am.

FRANK: Big deal.

MOTHER: I’m not going if you bring that tv camera.

DAUGHTER: Well, what will I do?

FATHER: Take the day off.

SON: I’d like the night off.

FATHER: The night is off.

SON: I’m off your wavelength.

FATHER: Wait a few years.

SON: I haven’t got time to wait. My real life is going by at its usual speed and nothing is happening!

FATHER: What can I tell you?

SON: I don’t know. What?

FATHER: Nothing, I guess.

MOTHER: What are you two talking about?

FATHER: You don’t want a lot of suggestions and put-downs.

SON: I guess not.

GRANNIE: What’s happening?

SON: Nothing, Mother.

MOTHER: Nothing, Mother.

FATHER: Some of it’s hard to take.

FRANK: I’ll say.

FATHER: I already said.

FRANK: Touchy. (Leaves with tray)

FATHER: It’s starting to rain.

MOTHER: No it isn’t.

FATHER: That’s good.

(SON leaves.)

MOTHER: What did you do before you had it?

DAUGHTER: Nothing.

MOTHER: Weren’t you happier then?

DAUGHTER: No.

MOTHER: I always thought you were a happy little girl.

Melissa Paper, David Brainard, Laurel Lyle, Suzanne Bodine as Daughter, Father, Mother, Grannie, costumes by Mary Gibson

GRANNIE: That’s because you were a happy little girl.

DAUGHTER: No, I’ve always been miserable.

GRANNIE: At least I thought you were.

MOTHER: I was. I’ve always been happy. I’m happy right now. I’m having a wonderful time.

GRANNIE: Me too.

DAUGHTER: You both sound just like Alex.

FATHER: Who’s Alex?

MOTHER: Her Alex, whose do you think?

GRANNIE: Dummy.

DAUGHTER: Do you know another?

FATHER: I don’t know any. Leave me alone.

SANDY: If we’re about ready to leave I’ll put the coffee back in the thermos.

(Pause)

FATHER: I’ll leave. (Exit)

MARGE (enters): Are you waiting for me? (Pause) Am I butting in? (Pause. Exit)

MOTHER: Why is everybody so touchy?

DAUGHTER: I’m not touchy, I’m depressed.

GRANNIE: I’m not.

MOTHER: I’m glad somebody’s keeping it together.

SANDY: Looks like we’re about to leave. (Exit)

GRANNIE: It’s all in your attitude.

DAUGHTER: Can I say something about that?

GRANNIE: Mind over matter.

MOTHER: It doesn’t matter.

DAUGHTER: It matters to me!

FRANK (enters): Alex? Oh, excuse me. (Exit)

GRANNIE: Or the other way around.

MARGE (enters): Psst. Come with me. (GRANNIE exits with MARGE.)

MOTHER: I’m glad we’re…

(Long pause)

DAUGHTER: What’s happening?

(LOOP)

“THE DINNER SHOW”

Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, 1996

I wrote this play in my cabin at Charlemont intending to do it at The Changing Scene in Denver just before my marriage to Michele Hawley, but it did not hit the right note, and I wrote a different play, “A Wedding Party,” for that occasion (see Denver Trilogy). In Santa Barbara years later Bob Potter asked me to participate in an evening of ten-minute plays his company Dramatic Women was producing at Center Stage Theater. Wondering what to do, I stumbled upon “The Dinner Show” in a notebook, never typed up. At Bob’s suggestion, Maurice Lord, a theatre student at UC Santa Barbara, directed. I had not previously found a director so attuned to my style, the play was beautifully realized despite production limitations, and this good experience made us want to work together again. We went on to co-found a Santa Barbara theatre company, Genesis West, and did many more plays together.

“THE DINNER SHOW”

For Michele—with apologies to Emanuel Peluso and Lucy Silvay

Jack

Mary

Emanuel

Lucy

Two musicians

A dining room. Blue sky with scattered white clouds is painted on the walls. The early evening sun shines in horizontally from right through a huge wall of plants. A breeze. Also practical lamps. The room is luxurious. Swinging door up right to pantry and kitchen; archway down left to entrance hall; two-musician band in up left corner.

While the audience is coming in, the table is being set for six: JACK and MARY are doing it together in a haphazard way, coming and going, getting dressed at the same time. Easy monotonous music. A cat. Birds. Fish. A dog. They keep coming and going during the following conversation.

JACK: What do we mean when we say “machine”? If we could agree on the meaning of just one word—

MARY: The best we can expect from words is good-intentioned lies.

JACK: Do you believe that?

MARY: Would I say it if I didn’t believe it?

JACK: You say anything.

MARY: Is there anything particular you’d like for supper?

JACK (After pause): No.

MARY: Any preferences?

JACK (Pause): No.

MARY (Pause): Then I’ll make soup. Is that O.K.?

JACK: Sure.

(Long space)

MARY: Do you mind if I use this chicken broth? (Shows can)

JACK: Was it here?

MARY: Yes.

JACK: It’s not new soup?

MARY: No. (Pause) The can is sealed. (Pause)

JACK: I’m sure it’s perfectly all right. It’s Campbell’s soup. Millions of people eat it every day and live.

MARY: I don’t want you to eat it if you’re not sure of it.

JACK: I’ll eat anything you give me. (Long pause) I wish they weren’t coming. I never have any time to read.

MARY: What are you reading?

JACK: I want to read the Don Juan books again. I reread the introduction to the last one. He says the world we live in, this world, the everyday reality we share—

MARY: —through words—

JACK: —is just a description of the world that is that we’ve been forced to agree on. They all say we can wake up if we work at it.

MARY: We do want friends, don’t we? In fact they’re your friends. Are you going to be hungry soon?

JACK: I can eat any time. I’m not going to want to eat much before… dark.

MARY: But it’s hard to cook when it gets… dark.

JACK: I know.

MARY: I see the… dark women in Benares crouched over a tiny single flame. Carbide. I think they use carbide.

JACK: This is my favorite time of day.

MARY: What are you looking at?

JACK: The sun, the setting sun. The wind waving the treetops wildly. The wood fire whispering in the stove. The smell of cabbage soup in the mountain air. (She goes out.) The cat rummaging through the asparagus. Your asparagus is doing very well.

MARY (Off): Did you feed your cat?

JACK: He’s not my cat. No. I never feed him before dinner. You know that.

MARY (Off): I’m putting it in the oven now. You should take it out in 45 minutes. I’m setting the timer. Are you listening to me?

JACK: No, but I can’t help hearing.

MARY:Where do you get your material?

JACK: From the trees. I am one of the trees. I’m just standing here. I’m rooted. I don’t have to try. I’m an evergreen, actually. I don’t get new leaves, I have to make do with the old needles. (She comes through wearing a light coat and carrying a suitcase.) Where are you going? (She looks at him but doesn’t say anything. She goes out.) Where are you going? (Sound of door closing. Flatly) Don’t go. (Pause. He slaps himself in the face. Long pause. He shakes himself sharply, as if shaking awake.) … in his commercial period which show much increased output and consumption. He repeatedly had maintained that he needed an office or studio where he could be alone and an occasional secretary. Now the time had come.

(No pause)

(Bright colored tv lights flood the set. Mary’s voice as NARRATOR takes over amplified from offstage. JACK continues in lip-sync but silent.)

NARRATOR (No pause): He met the challenge easily, as he’d known he would. He always had enjoyed being busy and learning new skills and technologies, and he needed competent people to play with. His personal life meanwhile was having its ups and downs.

JACK: I really don’t care.

NARRATOR: Do you love me?

JACK: I’m sorry, I’m thinking about something else.

NARRATOR: You’re angry. You’re really angry with me.

JACK: I really don’t care. (Doorbell chimes. JACK stops lip-syncing NARRATOR’s words.)

NARRATOR: He goes on as if. Nothing has happened.

JACK (Going off to door): The house hasn’t fallen down. The clocks haven’t stopped. (Off) There’s more than one reality.

(Sound of birds. Drums. The tv bright lights slowly fade out leaving setting sunlight streaming through the trees into the room of clouds. An Indian maiden enters stealthily from among the trees. It is MARY. She gestures to unseen companions not to follow. She looks to see how many places are set at the table. She looks at the musicians. She looks into the kitchen through the door. She goes out the other door. Long pause. Bird song continues. Also music. JACK comes in carrying a bottle of wine and a small potted pine tree, which he puts down in the middle of the table. He takes the wine into the kitchen, talking all the time to unseen people in hall.)

JACK (cont.): I’ll just put these things away. They’re perfect… I can’t stand a mess unless I made it. I always think it means something… Leave your things—here, I’ll help you. (Crosses out into hall) You don’t mind if I don’t hang them all on hangers. I hate hangers, don’t you? Here, I’ll just throw them on the floor behind the door. (He comes in carrying a fairly large potted palm, which he puts over by the musicians.) It’s perfect! Oh, look at that sunset! (He goes out and comes in with a case of whisky, which he takes out into the kitchen.) I love sunsets, don’t you? Doesn’t everybody love sunsets? Of course it depends where you’re watching them from. But you can say that about anything. Oh, what’s that? Oh! (He is looking at the sunset.) What’s happening out there?! I can’t make out what that is, it’s changing so fast! Oh! Come look! (Bright tv lights flash on. Curtain of leaves falls into place in archway left. JACK whirls. MARY as Indian steps partway in through the leaves. Long pause.)

MARY: I am trapped between your yes and your no.

JACK: I don’t know what you’re talking about.

MARY: Yes you do. You say one thing but you are thinking another. You make everything good when you are feeling strong. Then you change. But I will not be here.

JACK: Why are you doing this?

MARY: Because you will have killed me.

JACK: Are you staying for dinner, or what?

MARY: Do you want me?

JACK (Glancing at audience): For heaven’s sake—

MARY: Is it something I’m doing?

JACK: Is it something I’m doing? (Pause) Every word I say makes it worse.

MARY: Words! (She spits on the floor.) You are paper people. You make me talk so you can write down my words on paper. I must be interesting because you sell my words on your paper to other men who later give you pieces of other paper for them. They print these words many times on many papers and sell them for coins. You take their paper checks to your bank and get paper money. When you buy things with these pieces of paper you also get coins. These coins are taken from my body. You are tree but I am earth. I am the earth you grow in and rape with your paper! (Pause. He takes a handful of coins from his pocket and scatters them onto the table between them, where they crash into the china, silver, and glass. Pause. The tv bright lights slowly fade out leaving the room quite dark. The sky walls glow blue.) You are not tree. You are not earthling. (She crosses the room, he stands aside, she goes out through the plants. The bird songs have stopped.)

JACK (To audience): And in so doing I had squirted away a boy waiting to be born to us. So I come face to face with the mystical facticity of remorse. Is this something I should forget? (Hears something in the kitchen) Who’s that in the kitchen? (To audience) I mean, this is my actual life going by. (Pause) Anyway, that was.

(A crash backstage. The stage lights go off and low backstage lights go on. Through the transparent back wall MARY is seen sweeping up the pieces of a broken plate. Various props and backstage paraphernalia are also seen. JACK goes off as if he were invisible. He holds the dustpan for MARY as she sweeps the debris into it. He comes back onto the stage and takes the same position. TV bright lights come on. Music continues, transforming on some independent synchronicity.)

(EMANUEL and LUCY enter through the vines. They are identically dressed in yoga whites. They are both carrying potted trees, right in front of their faces, which they don’t put down.)

JACK (cont.): The sunset’s over. I’m sorry. This is twilight.

EMANUEL: I’d call it dusk.

LUCY: I’d call it night.

EMANUEL: Did you see the program about brain research? They almost know how to put a pacemaker in the brain.

LUCY: I’m going back to school.

JACK: What are you going to study?

LUCY: The brain.

EMANUEL: I’ve applied for a job as a forest ranger.

JACK: I’d like that.

LUCY: Anybody would.

JACK: Oh, I don’t know.

EMANUEL: Don’t disagree with her.

JACK: Don’t tell me what not to do.

EMANUEL: Sorry.

LUCY: That’s all right. He’s right.

JACK: He can follow the conversation.

EMANUEL: If that’s what she means.

LUCY: I’m going to school while he goes off into the forest. He wants to be alone.

JACK: Yes. I mean, do you?

EMANUEL: Yes. But I still want to be married.

JACK: You’re lucky.

LUCY: We’re all lucky. We’re lucky to be alive. We’re lucky to have each other, if we do.

JACK: Dinner won’t be ready till the timer rings. Just keep talking.

EMANUEL: Did you see the program about brain research? They almost know how to put a pacemaker in the brain.

JACK: Uh . . . Are you worried?

EMANUEL: No. Or rather, yes. About what?

JACK: About everybody turning into machines.

EMANUEL: We already are machines.

JACK: What do we mean when we say “machine”? If we could agree on the meaning of just one word—

LUCY: The best we can expect from words is good-intentioned lies.

(The timer rings: ding. The musicians stop playing. Pause. MARY comes in from the kitchen with a steaming soup tureen, which she puts on the table.)

MARY (To musicians): Dinner.

(They put down their instruments and come to the table. Everybody sits down at the table. Pause. Blackout.)

Copyright © 1974, 1996. All rights reserved.

“FAST FORWARD”

Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, 1999, 2007

David Brainard and Kinsey Packard as Stu and Fou in Maurie Lord’s production of “Fast Forward,” 2000 (Photo: Rod Rolle)

Bob Potter asked me to contribute to an evening of short plays about Santa Barbara. I had the idea for a play beginning with my first arrival in Santa Barbara in summer 1953, age seventeen, having driven alone from Kansas City in my mother’s Chrysler convertible. It became a chronicle of my many visits to my parents through the years as I was growing up and they were growing old. I wrote it in New York, in my room in an inexpensive hotel on 11th Street that Bob had recommended. Maurice Lord directed, and I was delighted with the cast: Jay Carlander as me, with Kinsey Packard and David Brainard as my parents. It was perfectly realized in my opinion.

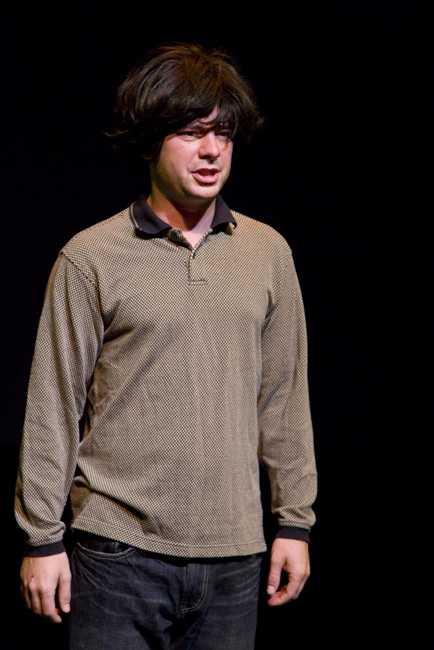

I revived it, directing it myself, as part of “Bad Dog and Other Plays” (see “Bad Dog”). There was something very sweet about having my son Alfred play me, and he did the role with sensitive simplicity and directness; I hope he will keep it in his repertory for many years. David Brainard gallantly reprised the role of my father, and Laurel Lyle, beautifully costumed by Mary Gibson, was exquisite as my mother.

“FAST FORWARD”

(TIM’s voice is heard in the dark.)

I drove straight through from Salt Lake City. I stopped in Las Vegas and stuck a few quarters in the slot machines, but there wasn’t any point in going to sleep. My mother’s Chrysler was solid on the road and I loved driving across the desert at night with the top down. I was seventeen. I had driven all the way from Kansas City, across the plains, over the mountains, through the arid colored rocks, under the starry canopy into starry California.

(The lights fade up, bare stage, TIM entering.)

The sun rose as I drove up the coast to Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara was my father’s dream. The ocean. Nice weather all the time. He could work half as much and make twice as much money, far away from his brothers and sisters with their attitudes and memories. I wanted to get there early and surprise him. He was at a motel on the beach that had two swimming pools.

(STU comes on in pajamas and slippers, rubbing his eyes. They start to hug but don’t. Instead STU shakes hands with TIM, firmly but with an odd pushing gesture. TIM cringes slightly. Exit STU.)

Dad had bought a store on State Street. It was one of the nicest stores in town, elegant and moderne. He put me to work in the stockroom in the basement, unpacking dresses, blouses, undies as they arrived, checking and counting them and putting on price tags.

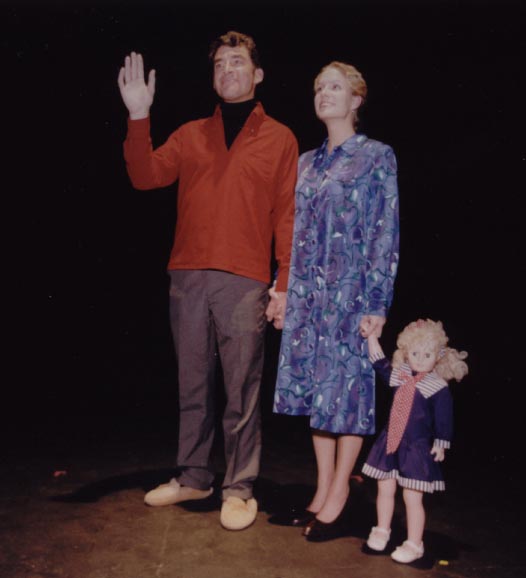

(FOU comes through leading BECKY by the hand. BECKY might be a doll.)

When Mother and Becky arrived we moved to a cabin at San Ysidro Ranch. I slept on the back porch. I drank red wine at a pool party there and got drunk for the first time. A friend took me down to the Miramar, and I threw up beside the pool. The next day I had dry heaves in the alley outside the stockroom. My father took me home.

(STU comes on in a suit and tenderly leads him off. TIM comes right back in.)

I went back east for college that fall and came here for summers and Christmases.

(FOU comes in talking silently on the phone, abruptly stopped by the cord.)

Mother booked me as a date for parties at the Coral Casino, and I started to make some friends among the Montecito kids. But after my short college career I moved to New York and only came for periodic visits. I liked the sunlight and bright colors. I liked to lie in the sun on the silver-painted roof over the garage, enjoying the heat on my smooth slim body. I liked to speed around the Montecito roads in Becky’s Austin-Healey. Otherwise Santa Barbara was too nice to be real. I couldn’t see the landscape as beautiful, in spite of what my father thought. The mountains were uselessly abrupt, the land was scruffy and brown where it wasn’t watered. He loved to swim, but I basically feared the ocean, which was almost always cold.

(STU bounces through in swimming trunks and towel, tries to drag TIM into the water, gives up, goes off.)

It will feel good afterwards, he said, but I wanted to feel good now. It was the sixties, and I moved to Greenwich Village and changed, and for a while I didn’t fit in so well in my parents’ ultra-respectable world.

(Puts on a longish shaggy wig.)

One time I brought my lover and a speed-freak friend when we were driving around the West, wanting to show them my other life. My parents were in Europe. We climbed over the garden gate to get into their house on San Ysidro Road and scared their German housekeeper, Gerte. But she recovered and made us a nice dinner, and the next day we drove on up the coast.

(STU and FOU come through carrying suitcases, looking baffled.)

I moved to the Haight for a while. I hadn’t been speaking to my father because of something he had said about my friend. I took a break from zazen and went to L.A. Driving back north with my cousin I stopped off at the house to see my parents. Mother was out, and Dad had been taking a nap.

(STU comes in, rumpled, in leisure wear.)

He wanted to be friendly, but we had swallowed some psychedelic and were flashing too fast to wait for him to wake up.

(Exit TIM leaving STU rubbing his eyes. Fade out. Lights right up, STU leaving, TIM coming in.)

I came back in the seventies with my bride, Rochelle. We wanted to live near our parents so we would “be there” for them when they were old. Her parents were in New Mexico surrounded by children, but mine were alone. So we came here after our honeymoon drive across the West.

(FOU brings him a glass of orange juice, which he drinks.)

My mother found us free lodging in the chauffeur’s cottage on a closed-up estate, bees humming in the walls. Rochelle took a job tooling leather in a factory in Carpinteria. I was strangely paralyzed. I had work in New York but I didn’t want to go back. I learned to strum a few chords on the guitar and sang folk songs for my bride. I applied for a few jobs but nothing clicked. All my father could find for me was day work gardening for his elderly friends. I took the test for mailman and made the list. But Rochelle was pregnant and we needed to get settled fast. So I lined up a job in Connecticut, and we departed, pulling a little trailer with our things, breaking my mother’s heart.

(STU and FOU come on to wave goodbye, smiling bravely; slowly sink into forlornness, beginning to be old; then gradually brighten, realizing it’s a beautiful day, and go off cheerfully, apart.)

We had two boys three years apart and brought them to visit many times. They learned to swim in the Miramar pool. At least Joey did. Sam stuck close to the steps and learned later at camp in New York. Rochelle stopped coming after a few years, but I kept coming with the boys. One year Becky and her second husband and their son came too. We stayed in a museum-like Spanish estate that belonged to a friend of my mother’s.

(STU crosses, elegantly dressed but looking frail, walking slowly with a cane.)

Our parents had moved into the Casa Dorinda, and they came for Christmas dinner. Dad had been injured when he was eighty in the surf at Cabo, and I admired his gallant style, but this would be virtually the last time he went out. They drove each other crazy cooped up like that. Too blind to read, Dad could barely walk and spent most of his time in his room listening to books on tape.

(FOU crosses with a gin and tonic.)

Mother couldn’t leave, and she couldn’t have people over because he was always there. She had been drinking steadily for years but now she took it further. When I came to visit they had me over for dinner, which I came to dread. Mother got more and more incoherent. Dad was sober but just as bad—grumpy, cold, picking on her and putting her down. I liked being with either one of them separately, but together they were hell. I’d come out into the fragrant night holding my head in my hands and staggering around.

(He demonstrates.)

That went on until he died. He was in bed in the medical center the last few months, miserable, and she tried to write him off, rejecting his plea to come home to die. When he died she was down the hall recovering from knee surgery. I came out, and although I was furious at my mother for the way she had treated my father at the end, the only thing to do was to forgive her. I stayed for six weeks, sleeping in my father’s bed. I went back to New York for Christmas, uprooted myself, and moved to Santa Barbara, driving across the country in a twenty-foot Isuzu truck. Now that my father was gone, I could see how beautiful Santa Barbara was. I felt empowered the minute I got here. Everything was easy compared to New York. Before long I was lucky enough to link up with my beloved, Sheryl, whom I had known here as a teenager and not seen for thirty years. We decided to stay together for the rest of our lives. Sam came to live with us and go to high school. Joey came for a while and built up his strength.

(He goes off and brings in FOU in a wheelchair, eating chocolate mints.)

I visited my mother two or three times a week, year in, year out. And…

(Pause.)

… well…

(Pause.)

… here I still am.

(Pause. Fade out.)

Copyright © 2000. All rights reserved.

“VORSPIEL NACH MARIENSTEIN”

Caffè Cino, New York, 1967; The Changing Scene, Denver, 1968.

I wrote this little play with its simultaneous soliloquies at a late-night party with Johnny Dodd and Ondine, who were serious opera fans. It was done as part of a show I put together at the Caffè Cino in April 1967 to fill the week after my production of Soren Agenoux‘s "Donovan’s Johnson" closed prematurely. Ondine played Wagner, Charles Stanley played Ludwig, and Deborah Lee played Kundry. Magie Dominic made the waterfall out of cardboard and strings of blue sequins.

In the Denver revival, directed by Robert Breuler, Tom Eagan played Ludwig II and my cousin William Lucas played Wagner. I wish I’d seen it.

“VORSPIEL NACH MARIENSTEIN”

by John P. Dodd, Ondine, and Michael Smith

Marienstein. Ludwig II, Wagner.

LUDWIG: I am guilty of stifling my life, guilty.

WAGNER: I only want to be myself. (Aside) Why does he always wear black?

LUDWIG: He’s in mourning for his life.

(They part to opposite sides of the stage. They glance at each other and look away. Simultaneously)

LUDWIG (Romantically): All my dreams come true. What am I thinking about? I think of nothing. All my friends are crazy except I don’t have any friends. It’s more than just funny, it’s silly. It’s a little dismal. Friendship is fatal—I’ll take romance… What could he possibly want from me? Oh to be possessed! Why not a love duet before they’ve even met? I don’t want to burden him with that kind of remorse. The thought is good, only it’s not well put. (Weeping) What a clumsy moment! I can’t say the universe is shit. Wagner could. That’s my favorite part of it. I’m not an actor. It’s not hard to say these things. That was the Ludovisi nose. Madness doesn’t have to relate to anything. I admire him for the right reasons. I need something concrete—that’s a definite statement, but… My ineptness is getting in the way of my self-consciousness. If that isn’t a self-conscious thought! She has the biggest tits in Leipzig. The whole thing is going to be a terrible disaster. I’m a disaster myself, and Wagner knows I’m a disaster.

WAGNER (Challengingly): All right, I couldn’t afford it. It should be a privilege to meet a king. Actually I’m interested. I’d like to meet anyone under those circumstances. He doesn’t have a friend in the world. Maybe he’d like to buy one. I dare not… What could he possibly want from me? There’s no reason to wait. If only I were totally subjected to the moment not realizing I am totally subjected to the moment. I’d like to shit in his face and get the money and go home. Why fuck around? I hate to say that, but it is real. He’s going to fall apart eventually. This isn’t an Italian opera. You have to get it together into one version, preferably the first thing that pops into your mind. I think that’s a little too clear. (Laughs cruelly) I hear he’s a homosexual. I love that line. I know he’s possessed, but he doesn’t have any position except with his demons and horrors, and I have the biggest tits in Leipzig. They wander out of their own lives and say something, and all the Beethoven fans stand up and hiss. I wonder what he’d give me for my brain. Kundry has to be brought in at every possible moment, but she has to be in a thicket sleeping with the earth. Parsifal… Parsifal… (Softly) Parsifal…

(KUNDRY appears and screams until the end of the scene.)

LUDWIG: I’d go anywhere. Oh I wish I were dead.

WAGNER: I’m always looking at the sky. Let’s get on with it.

(They turn and begin moving slowly toward each other.)

LUDWIG: This is the first thing he’s ever given me. I know he’s my master but I don’t know how to be humiliated. I’ll be ravaged and divine. I’d rather serve him than die. How much of it will I get? What does he want? (Long sigh) Finally I am humiliated. No wishes, no dreams, nothing, nothing, nothing is too romantic. (One sob)

WAGNER: He has to be constantly humiliated—my family make a regular ritual of it. He has to be a king or die. If I can’t teach him, who can? How much will I get for it? What does he want?… Now we have to get very romantic. It is not the final humiliation. I passed your mother’s heart and heard it die.

LUDWIG & WAGNER (In unison): We are both getting too far into this. I hate relating but it’s far too late. Bury me in your craziness or I will bury you in mine. Let’s not talk. Kisses are the language of love.

(They stop the word with a kiss. A waterfall falls on them and they disappear. So does Kundry.)

“OLIVER & LUCIFER”

I thought of doing this play, written c. 1968, as part of “Bad Dogs and Other Plays” in Santa Barbara in 2007. I believe in it but on reflection chose not to revisit those feelings or make Alfred embody either of the two unhappy characters, who set a sorry example of love. Instead I would revive “Fast Forward,” which is more fun and audience-friendly, with Alfred playing his father in a better state of mind.

“OLIVER & LUCIFER”

Scene 1

O. What is that crackling sound?

L. Rain? Fire? A loose connection? There is no meaning to it, just a kind of music. Thunder? Was it only last year people went to the moon?

O. It’s exciting but it doesn’t give me a hardon.

L. I wish it did.

O. I don’t like it. I don’t like to go out in it. I like to stay in out of it.

L. Please! I beg you!

O. What is going on here? You make a point of bringing me down. I am starting to be sick of it.

L. I can’t help it. You make me unhappy whether or not I am with you.

O. Really?

L. No, of course not, what am I saying? Have you been eating garlic?

O. It was in the salad dressing.

L. Are you an enemy of rain?

O. No, of course not. Rain is good.

L. Do fish call bubbles rain?

O. What is the significance of the numbers 13 and 18?

L. Are you really sick of me?

O. Not yet.

L. I am sick of myself. I can’t stand it here. All I can think about is sex and death in parts. I like the taste in my mouth—but I am falling to pieces. What can I say?

O. Say it or don’t.

L. I can take care of myself if you’ll just leave me alone.

O. Is that what you want?

L. No! I didn’t say that! But it comes up out of the gutter on nights like this. And I am helpless. I’m not really, but I like to think I am being carried away, and then I actually get lost. It is very boring.

O. Have you fallen asleep again?

L. Yes, and you are a character in my dream. I have never seen you before. Am I supposed to know you? Do you represent someone?

O. Yes.

L. Don’t tell me! I don’t want to know!

O. Wake up.

L. Are you flirting with me?

O. Yes I am. Do you like it?

L. I don’t believe it.

O. Shall I give it to you in writing?

L. Try me.

O. Don’t you think you need a woman’s touch to make it come alive?

L. What kind of a thought is that?

O. I’m sensitive.

L. I keep feeling you are not here.

O. That’s a terrible thing to say.

L. Sometimes you’re not.

O. Then it’s okay.

L. It is not okay.

O. If I don’t go away you will.

L. What am I supposed to do? Twiddle my thumbs?

O. Hey! Take it easy!

L. Oh yes! Give me what I need. Tell me to relax. Teach me to be myself.

O. Put on another record.

L. The other side?

O. Or something else. I’m too crazy to care. Play something sentimental if you want to. It is almost time to go anyway.

L. This always happens.

O. Hurry up! What are you waiting for?

L. My mind to clear.

O. That’s what I mean.

L. That’s what I mean.

O. That’s what I mean. I think it’s funny, in a way. It’s fine.

L. That’s what I mean.

O. Cut it out! I am not as bitter as you think. Have I said this before?

L. Not exactly. This tastes like banana. That camel story is funny.

O. Gutter to gutter.

L. It will look small on stage.

O. I hope so.

L. I am feeling very weird. Have you even noticed?

O. I know. So am I. I need a little rest.

(Pause)

L. I know. I’m silly.

O. We are both tired.

L. I don’t know how to live with such confusion

O. I have to go.

L. Wait till the end of the record. I need some more moments to cherish.

O. Will you be here?

L.. Depending on certain negotiations.

O. Will you?

L. What can I say? I will do my best.

O. Well, I’ve got my war boots on. One more for the wet road. I guess my optimism is wearing a little thin. But I am not making it up, it is coming in from the so-called environment. I’ve got to get out of here! (Tears himself away.)

(Lucifer left alone.)

Scene 2

O. Did you hear the one about the donkey dealer? Not much money in the well, he says, better mind me pins and prickles.

L. Oh no! (Laughs wildly)

O. So I says to the wife, Wednesday, we’ll see you Wednesday, and off I go. Bring me a present, she calls after. For answer I lift up the beastie’s tail. Fine dinner it was, too.

L. For four?

O. And the cousin’s brother. He’s the one I had in the shed when he come out for wood. Prettiest arse in the tribe. Didn’t get a morsel of the goose. Afterwards I lit out for the city, set myself up a whole new life.

L. When was that?

O. Thanksgiving. I been thinkin’ about what you said. Seems like we could sell the animals, get ourselves some sharp clothes, and put on a little show.

L. Naw.

O. Okay. Cause I like it fine the way it is.

L. Me too.

Scene 3

(Oliver alone dejected. Lucifer enters.)

O. Wow!

L. Hello, baby.

O. Oh, wow!

L. I came to help you.

O. You’re too much!

L. I didn’t know if you’d be here.

O. I was just going out. I just came in. I couldn’t remember where I was supposed to be. Your timing is perfect.

L. I couldn’t think what I was doing there. I got into the car to go to the store and then I just drove here.

O. When are you going back?

L. I’m not. Well, maybe after the weekend.

(Long pause)

O. Can I come with you?

L. I wish you would.

O. I can’t. I have a show.

L. You always have a show.

O. I wish.

L. What’s the point?

O. Survival. I have to work. Remember work?

(Pause)

L. What do we have to talk about?

O. You talk about what you’ve been doing and I talk about what I’ve been doing. We ask each other questions.

L. I read “The Magic Mountain.” (Pause) I get it all worked out in my head but then when I come here it is all different. It is real pain.

O. I haven’t slept at all.

L. Then when I go away it lifts after a short time and it’s nowhere heaven. Sometimes I fly. I turn on in the car and play the radio. I listen to grand lyrical music like the Enigma Variations and glide along smooth empty roads with long fast curves and graceful ups and downs. Then I arrive somewhere and fit right in. I make myself a snug little place to settle down. I go along with whatever is happening, and I am happy for a while. But where are you?

O. Go fuck yourself.

L. Then just as suddenly, or even more, I pack my bags and load up the car and fly away.

O. Why are you telling me this? I can’t even go out of the house. I can’t even get out of bed.

L. Aren’t you glad to see me?

(Long pause)

O. I’ve really been unhappy.

L. I used to be unhappy.

(The actors switch roles.)

L. as O. I wish I had known.

O. as L. I told you.

L. as O. Yes, I remember. I wish I had known something to do about it.

O. as L. There is nothing to do about it. Let it pass. Don’t panic. Don’t hold onto it.

L. as O. Will it make me as strong as you?

O. as L. You are stronger than I am.

L. as O. Ha.

O. as L. I have enough to do for about four lifetimes without even doing half of what I want to do.

L. as O. Are you going to do everything?

O. as L. No.

L. as O. How do you decide?

O. as L. What?

L. as O. What are you doing here?

O. as L. I came to see you.

L. as O. What’s happening in the country?

O. as L. Nothing. The usual. What’s happening here?

L. as O. It’s too disgusting to talk about.

(Pause)

L. & O. (In unison, to each other) Robbing your friends is the easy part. I no longer know who I am. I know who I used to think I was. I think of you and whatever I am doing turns stupid and empty and I can’t think of what I am doing there wherever I am. I think I am going crazy. Now that we’re together . . . isn’t one of us about to leave? (Pause) Yes, but what are you thinking? (Pause) Please tell me all your appointments for the next month. I don’t have a single plan. Whatever I had fell out from under me five minutes ago. Ugh! All lies! I know exactly what I am doing but I am not sure what you are doing. You say so much and I have to decide what to believe. But that doesn’t make you do it. (They gradually switch back to their usual roles.) I don’t want to say another ugly word. I am happy to see you. I would like to believe you are happy to see me. Can’t we relax for a minute? Whew! It is really much simpler when you are not around but I get so lonely I can’t stand it. I don’t know what else I am doing here. I have to be someplace! Why are you looking at me like that? I just happen to be perfect for the role, better get with it.

O. I’m supposed to be somewhere. Do you want to come with me?

L. That’s the idea.

(They go out together.)

Scene 4

(Lucifer alone. Oliver bursts in.)

O. Aha! Caught in the act!

L. (Scarlet with shame)

Scene 5

O. Don’t mess around with anything, that’s my motto.

Scene 6

O. Any attitude is a mistake.

L. That’s just an attitude.

Scene 7

(Shattered.)

Copyright © 1968. All rights reserved.