“Dogs Bark All Night”

Genesis West, Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, Nov. 24-Dec. 9, 2000

Things were getting crazy in Santa Barbara. I had been unduly busy for months. I was winding up my job editing Santa Barbara Magazine, and I had produced a big play by George F. Walker at the Lobero Theatre. I was also vice president of the Lobero board, which was in a state of wretched disarray. That summer I finally had some time free. I wanted to write a play to do in the fall, and I went to Taos to write it. I would also get to see Julian, who was living there. He helped me find a room to rent in the house of Judson Crews, a poet now elderly and chair-bound, a very sweet man. I stayed two weeks. I was reading a history of war and some alarming political analysis in the New York Review of Books. I was deeply offended by the horrible actions my government kept committing, particularly the first Gulf War with its burning oilfields and Highway of Death. One seemed to be weirdly silenced by the inexorable continuity of destruction. I made up a woman who had been a radical activist in the sixties, had gone underground, and had constructed a new identity and life, with a husband and teenage son who knew nothing of her political past. Her choices had condemned her to silence. But a book of photographs of the burning oil wells in Kuwait upset her so much that she had to speak out. I had never written so directly, both politically and emotionally, as I created this little family in stress.

I imagined the play specifically for Center Stage Theater, using the space simply and freely, with video projections opening up the images inside the characters’ heads. Maurie Lord directed it, with a lovely cast, especially Laurel Lyle as Janice, filling the role with powerful conviction. As luck would have it, throughout our run the Bush-Gore election was undecided; it was possible to hope. And my play is indeed hopeful, unrealistically letting Janice off, ending with an idealistic image of Janice running for President, supported by her loving family. I love it, but I have long thought I needed to write a second act to this play that shows what would really happen; but that would be too depressing.

Production Credits

“Dogs Bark All Night” was presented by Genesis West at Center Stage Theater, Santa Barbara, November 24-December 9, 2000. It was directed by Maurice Lord with the following cast and crew:

| JANICE | Laurel Lyle | |

| BILL | David M. Brainard | |

| VERA | ClaireMarie Mallory | |

| TOMMY | Steven Gonzales |

with special guest appearances (on video) by Braden McKinley and Leslie Gangl Howe

| Costume Design | Kimberly Galloway | |

| Lighting Design | Michael Smith | |

| Video Editor | Nick Vincent | |

| Choreography | Steven Lovelace | |

| Wardrobe | Courtney Ermac | |

| Sound Design | Parry Gripp | |

| Stage Manager | Alison Torbitt |

“Dogs Bark All Night”

Characters

| Janice |

| Bill |

| Vera |

| Tommy |

Scene 1

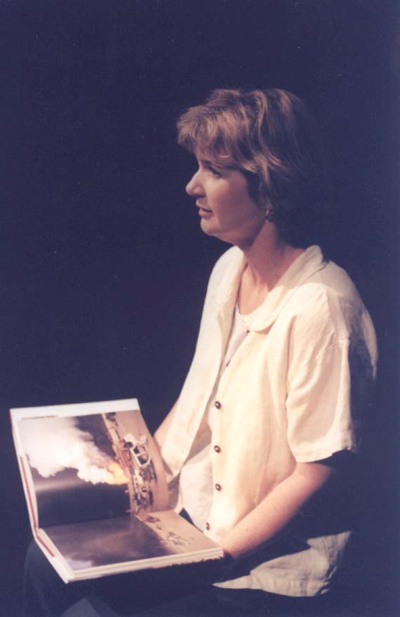

Tucson, July 1991. JANICE sits in a pool of light facing a video camera on a tripod, its back to the audience, a book open in her lap. She is an attractive woman in her early forties, tense but controlled. Behind her, her image is projected live on the back wall of the stage. After a pause she begins speaking quietly but with passion.

JANICE: I have to speak, after all these years. It’s these pictures, vast fields of burning oil wells raging out of control, poisoning the ground, poisoning the air, wasting and ruining the earth. Pointless, stupid destruction. They are fiercely beautiful, on a scale I can’t imagine, mile after mile across the measureless, horizonless desert. Kuwait is tiny. How is it possible this destruction is so large? Whom does it help?

(She turns a page.)

And here is the Highway of Death. They were defeated. They were not shooting us, they were fleeing for their lives. Their country was destroyed. We had won. Our pilots came in behind them low, blasting them with machine guns, cannons, rockets from the bellies and wingpits of their planes, and jellied fire, their fingers on the buttons, devastating trucks and tanks, buses and cars, burning people who had been forced to fight, ending their terror and agony in charring death. Not the officers. They’d flown home.

(Looking up.)

I can’t understand why my country did this. I willingly pay my taxes. I sign on the line. People I used to know marched against this war for six months before it started. It wasn’t sudden anger, not a hot burst of madness but slow, deliberate, political, like the missiles in the silos in beautiful Kansas. They’re not stone-pointed spears, they’re modern killing machines, professionally engineered and profitably manufactured. It took very smart people to make them work, bureaucracies to dig the holes, hard-working construction crews to be corrupted by doing the work of death. Good people. People I used to know tried to reason, tried to obstruct, tried to countervail against the juggernaut and failed, failed again, and saw the country change, not by accident and bad luck but by policy and manipulation. I know, we were never pure, but now there’s barely a pretense of legality, much less compassion, not even talk of progress toward social justice. Only money speaks. We’re scared to do anything but keep it going, buy better stuff, go to better restaurants, fix up our kitchens, tune up our bodies, stay young, be rich. Fuck everybody else. People I used to know…

(BILL, her husband, has come in quietly and heard some of this. He interrupts from the shadows.)

BILL: What are you doing?

(She freezes, thinks, breathes, relaxes, turns to him and smiles.)

JANICE: Ah, nothing. A fiction. Something I’m working on. You’re back. (He comes to her and kisses her, on camera.) What happened?

BILL: What are you doing?

JANICE: What happened?

BILL: I had a call from Tommy’s school.

JANICE: At work?

BILL: You didn’t answer. Where were you?

JANICE: What happened? Is he all right?

BILL: He wasn’t there. He hadn’t been there all day. What happened this morning?

JANICE: Nothing. I made him his lunch. He went.

BILL: Did he say anything?

JANICE: He kissed me. He said he loves me. It was sweet. I love him so much.

BILL: Then I got a call from the police. They stopped him at the border.

JANICE: One of these times he’s going to make it. Are you ready for that?

BILL: Where were you?

JANICE: I do things.

BILL: You don’t. You can’t.

JANICE: I can. I’m a normal person.

BILL: Since when?

JANICE: Since… since the war.

BILL: What war?

JANICE: The Gulf War. Desert Storm. Where have you been?

BILL: What are you talking about?

JANICE: I bought this camera. I’m making a…

BILL: What?

JANICE: People I used to know…

BILL: What people? You don’t know any people.

JANICE: No, you’re right. Bill, go away. Come back later. I don’t want to talk about this.

BILL: I have to go pick him up.

JANICE: Thank you, darling.

BILL (Examining camera): This is a beautiful piece of equipment. Where did you get it? How much did it cost?

JANICE: I bought it for you. Then I thought…

BILL: What?

JANICE: Is it the right kind? Is it what you wanted?

BILL (He zooms in on her eyes. Freeze): It’s perfect.

(Pause. Blackout.)

Scene 2

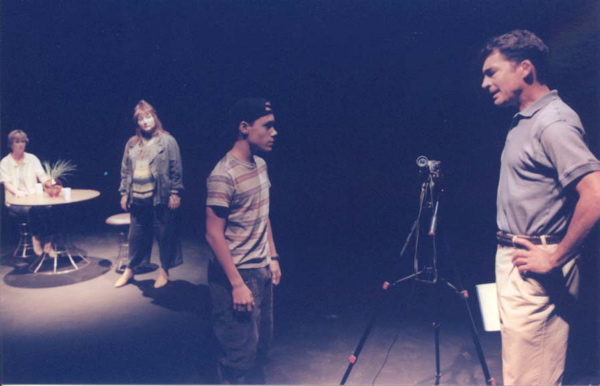

At one side of the stage, at a small table, JANICE is talking to Bill’s sister, VERA, who is pregnant and upset. BILL is at the camera, projecting a series of tight shots of young soccer players in action, taking notes on a yellow pad. At the other side of the stage, as if in another room, Bill and Janice’s 15-year-old son TOMMY is lying on his bed reading a comic.

JANICE: How did it start?

VERA: I told him I want a divorce. Now I’m afraid to be in the house with him.

JANICE: You can’t stay here.

VERA: Why not? You have plenty of room.

BILL: Of course she can stay.

VERA: Stay out of this. I’m talking to Janice.

JANICE: You can’t leave your house. He’ll say you abandoned the marriage. He’ll get Suzy and the house. It’s in both your names, right?

VERA: I paid for most of it.

JANICE: Can you prove that?

VERA: He dragged me up a flight of stairs. I’m afraid of him.

JANICE: I’ll come over and stay with you. Have you talked to your daughter?

VERA: He told me not to.

JANICE: So what?

VERA: He was mad that I talked to my girlfriend.

BILL: That’s ridiculous.

VERA: He doesn’t want a divorce. He should have seen this coming but he didn’t. He says he loves me but he really just needs me. What am I supposed to do?

JANICE: Have you talked about it calmly?

VERA: We’ve been to counseling but he gets mad there too. He says I bully him. He won’t talk about his violence. He says he was upset.

BILL (Calls): Tommy, come in here.

(No response.)

VERA: It goes way back. His father used to beat up his mother. He told me about it. It’s so sad. Then she left, and his father couldn’t deal with it, and so his grandparents brought him up. They were very strict. They hit him.

JANICE: I see.

VERA: I understand why he doesn’t want to let me go. But I’ve made up my mind.

JANICE: You should go to mediation and try to work it out so you don’t have to go to court, which will cost you thousands.

VERA: He wants to choose the mediator. He doesn’t trust anybody I come up with.

JANICE: Fine, let him. Do you have a lawyer?

BILL: Tommy!

(No response.)

VERA: No.

JANICE: You need a good lawyer to protect your interests. Otherwise you’re screwed. And Susan is screwed.

VERA: I have a will.

JANICE: From when?

VERA: Before we were married.

JANICE: It doesn’t apply. If something happens to you he’ll get everything. Do you want that?

(BILL, annoyed, has risen and gone into Tommy’s “room.”)

BILL: Tommy. (TOMMY looks up.) Didn’t you hear me?

TOMMY (Sullen): What?

BILL: Come in here. I want to show you something.

TOMMY: I’m reading.

JANICE: That’s the way marriage works.

BILL: You’re reading a comic.

TOMMY: I like comics.

BILL: Comics are garbage.

TOMMY: Please, Dad.

JANICE: You gave yourself to him. Now you’re taking yourself back.

BILL: Come on. You can go back to it.

(TOMMY reluctantly follows BILL back to the video camera.)

JANICE: I’ll find you a lawyer, but don’t say anything to Jack.

VERA: I tell him everything.

JANICE: Honey, this is tough stuff. It sounds like he’s going to fight you on this. He’s scared and dangerous. The rules have changed.

(BILL gets excited showing TOMMY the soccer video, replaying one shot, finally in slo-mo.)

BILL: See how he comes in on a curve? See how he moves the ball? See how he curves his foot? He doesn’t kick it with his toe! He doesn’t kick it! Look! That’s what I’ve been telling you. Do you see? Look! See? There! That’s it! That’s perfect!

(Everybody freezes, including the image. Hold hold hold. Then:)

TOMMY: I hate soccer. (The ball misses the goal.) He missed. Ha ha.

BILL: What did you say?

TOMMY: Dad, I don’t want to play soccer anymore, O.K.? I’m sorry.

BILL: You can be good. You can be great if you work at it.

TOMMY: I don’t want to do it. I quit.

BILL: You can’t quit. It’s the middle of the season.

TOMMY: Too fucking bad.

(BILL raises his hand to hit him. TOMMY cringes. BILL stops himself.)

BILL: So what do you want to do, lie around and read comics?

TOMMY (Pause): Maybe.

BILL: We’ll talk about this tomorrow. (No response.) Janice?

JANICE: This is between you men.

VERA: Suzy wants to play soccer. Why don’t you coach her? It would mean a lot.

TOMMY: Can I go now? May I go now?

BILL: We’re not through with this. Yes. You may. Go.

VERA: Will you? (TOMMY goes back to his room?) Bill?

(BILL goes back to the videa camera and reruns the shot of the perfect kick that misses the goal, rapt.)

JANICE: Do you have trouble getting men to listen to you?

VERA: So what was he doing at the border?

JANICE: He said he was going to live with his father. He didn’t tell them, though, thank God.

VERA: He’s still in Mexico?

JANICE: Yes. Bill took him across last summer. It’s tricky but it was O.K. once.

VERA: What’s the big secret?

JANICE: He has a past. It’s ancient history.

VERA: Does he want him?

JANICE: He wants him but his wife doesn’t want him. I’ve been through it with them. His wife likes him but he gets jealous and she’s afraid it would wreck their marriage, which is difficult enough, with his injury. Anyway, I want him here, I want him with us. We have a good life, it’s good here.

(BILL shuts off the video and joins them at the table.)

BILL: And I want him. He’s my son too.

JANICE: You’re a good father. You’re a good man, Bill. None of this is your fault.

BILL: What has that guy done for him? Nothing.

VERA: Bill, this isn’t about you.

BILL: To me it’s about me. To me this is my life. (The women look at him.) I feel like I have to apologize for being a person. There’s nothing wrong with being a man. There’s nothing weird about liking sports. Janice is the one who’s weird. She won’t go out of the house.

JANICE: I go into the yard.

(Dialogue contines as TOMMY finishes the comic, gets up, and wanders out to the video camera. He puts in a different tape or cartridge and projects lyrical images of himself dancing. It can be any kind of dancing_—_tap, hip-hop, modern, whatever the actor can do. After a bit he starts dancing with his image, using the whole space upstage.)

BILL: She doesn’t have a bank account. She doesn’t drive. She’s never had any friends. I don’t mind. She had a hard time. I love her and I want to take care of her. But that was a long time ago.

JANICE: I’m a private person. You know that. I like to stay home.

BILL: You’re like an invalid. What’s wrong with you?

VERA: Bill, stop it. What are you doing?

BILL: But I’m not good enough. He wants to go back to his “real” father, who walked away when he was nothing but a little ball of cells.

JANICE: Cut it out, Bill. I left him. Get a grip. Kids grow up and leave. Then what? That’s what I want to think about. The parent thing is pretty much done. Now what’s your excuse?

BILL: For what? I don’t need an excuse.

JANICE: I do. For consuming way more than my share without producing anything. For eating more than I want when people who work way harder than I do are hungry and sick, living five to a room, if they’re lucky. Or ten.

VERA: Listen, you guys, I don’t need you fighting, I need you happy.

BILL: We never fight.

JANICE: We are happy.

VERA: Well I’m not happy. Jack and I fight all the time, and even if we didn’t, I still wouldn’t be happy, because I don’t love him.

JANICE: I’m not going to say I warned you.

VERA: I thought I could learn to love him, the way you learned to love Bill, but I didn’t, and so his galling limitations didn’t come to see amusing, like yours, or yours, but eventually made me hate him.

BILL: When was that?

JANICE: I saw it last summer at the lake. We talked about it.

BILL: It doesn’t seem like a very good time to get pregnant.

VERA: We thought it would help. At least I did. He doesn’t even notice.

BILL: He notices.

VERA: He pretends he doesn’t. (She starts to cry.)

JANICE: Oh, honey, I’m sorry. I was being so selfish. I’ll follow you over to your house. I can stay if you need me. Or we’ll bring Susan over here. (To BILL.) Can I take your truck?

BILL: What?!

JANICE: Or the car. One of them. You don’t need them both. I drive. I know I always told you I don’t, but I do.

BILL: You don’t have a license.

JANICE: I got a license last week. (Shows it to him.) I’m sorry I deceived you. I won’t do it anymore. I’ve decided to take my chances.

BILL: What happened?

JANICE: The war. Six months of propaganda. A hundred thousand Iraqis dead so the military could test their new approach. RMA, they call it. Revolution in Military Affairs. Sorry.

BILL: I don’t know what you’re talking about.

JANICE: Can I take your truck?

BILL: Sure. (Hands her the keys.)

JANICE: Come on, Vera. (To BILL.) Are you O.K. with Tommy?

BILL: I think so.

JANICE: You’ll be fine.

(Goes.)

BILL: I feel like she’s a different person all of a sudden.

VERA: She loves you. Don’t let her down.

BILL: I haven’t done anything. Why didn’t you tell me what was going on with you and Jack? I asked you. I thought something was wrong and you denied it.

VERA: It’ll be all right. Janice doesn’t have to stay over. But it’s nice of her to come over for a while.

BILL: We’re family. We’re the only family she has. Have you told Mom what’s going on?

VERA: No, and don’t you say anything. I may change my mind. (Kisses him.) I think you should take Suzy under your wing and let Tommy free. Think about it.

(She goes. BILL turns and watches TOMMY dancing. After a moment TOMMY stops dancing and goes to the camera, looking at BILL. After a moment he switches it off. They look at each other. Blackout.)

Scene 3

JANICE is sitting crosslegged on a bigger bed in a pool of light upstage of TOMMY’s. BILL is standing beside the bed. Projected huge behind them, changing only at very long intervals, are the photographs from Desert Storm.

BILL: I feel like you’re a different person. You’ve changed. I don’t know who you are.

JANICE: I’m the same person. You know me. I’m the person who loves you. I’m the person you love. I haven’t changed, I’ve just changed my mind about a few things.

BILL: I don’t know you.

JANICE: You know me. We’ve been together every day and night, give or take a few, for fifteen years. You’ve been inside my body and my soul. We’re as close as two grown-up people can be. It’s true that you don’t know everything about me. How could you? How could I tell you?

BILL: You could try.

JANICE: How, with words? You know me better than words, beyond words. If I give you words, we’ll disagree. We have different opinions.

BILL: About what.

JANICE: Like this war. You think it’s a good thing. Normal.

BILL: We had to do it. I don’t like it, but Saddam’s a little Hitler. He crossed the line. We couldn’t let him take Kuwait. He has one of the biggest armies in the world. It’s like Austria, or Czechoslovakia. What would be next? Saudi Arabia? Israel?

JANICE: That’s what I mean.

BILL: We were humiliated. After Vietnam nobody thought we had the will to fight.

JANICE: Yes, I understand what you’re saying.

BILL: It’s a matter of honor.

JANICE: Bill.

BILL: We stopped too soon. Bush was a wuss. We should have stormed right into Baghdad and gotten rid of that little bastard once and for all.

JANICE: Bill.

BILL: What.

JANICE: These are words, Bill. They’re not even your words. They’re common coin.

BILL: You’re a pacifist, is that it? I suppose that goes with the veggies and tofu.

JANICE: Is this really what you want to talk about in our bedroom, where we love each other, where we put off all our armor, where you are as naked to me as I am to you, where we share our deepest desires? I don’t love your opinions or your loyalty to the American way of life, Bill. I love you. Come sit down.

BILL: The facts. Just give me the facts. How come you know so much about lawyers? Why did you pretend you couldn’t drive? Who are these people you used to know? Used to know? Why don’t you know them anymore? Why don’t they ever call, or write?

JANICE: No. That won’t help.

BILL: I need to know.

JANICE: Not now. I’ll tell you everything eventually. I’m working it out. I hate having secrets from you, believe me.

BILL: Trust me, you said, and I did.

JANICE: You can.

BILL: I love you.

JANICE: Let’s talk about your sister. She needs our help. She’s pregnant, and she’s married to a man who hits her. I’m afraid for her.

BILL: Afraid of Jack? He’s crazy about her.

JANICE: Exactly.

BILL: It’s an expression. Stop jumping on my words.

JANICE: I’m sorry. I know it’s annoying. Please, Bill, sit down.

(She reaches out to him lovingly. He sits on the edge of the bed.)

BILL: He’s always been perfectly nice. I think of Jack as a model husband. I wish I was as even-tempered and smooth as Jack. He makes me feel like a boor. I don’t know how to dress or brush my hair. I don’t know what wine to take to dinner parties. He gives her such wonderful presents. Aren’t you envious? I want to give you presents just as much.

JANICE: You’re fine, Bill. I don’t want more stuff. Thanks for the thought. I love you just the way you are.

(She takes his hand.)

You’re right, he’s very nice at family parties and makes all the right moves. But he’s not nice when they’re alone. He has temper fits.

BILL: I’ve never heard him raise his voice.

JANICE: You’ve heard him put her down, though, in front of other people. You’ve heard him make jokes about her work. You’ve even laughed.

BILL: I know. I was embarrassed.

JANICE: He screams at her when they’re alone. And she screams right back at him. She’s a complicated person too. Susan has been waking up with nightmares. And now he’s started hitting her.

BILL: Did she tell you that?

JANICE: Then he’s sorry and begs her forgiveness and promises never to do it again. He buys her an expensive present. He takes her out to a fancy restaurant, or to the Caribbean. He makes love to her slowly, the way she likes, or used to like. And then two or three weeks later, bam. It’s a pattern. I know about it.

BILL: How do you know about it?

JANICE: I read books.

BILL: I would never hit you.

(He has softened and moved up onto the bed. They sit close together.)

JANICE: I know you wouldn’t. I wouldn’t be here if you did.

BILL (Laughs): I guess I know that.

JANICE: Anyway, she doesn’t love him.

BILL: I know. She hasn’t really been happy with him. I’m sorry about that. I feel so lucky to have you.

JANICE: She’s in love with someone else.

BILL: What?!

JANICE: She has a girlfriend.

BILL: You’re kidding!

JANICE: She’s in love with a woman.

BILL: Are you serious? I had no idea.

JANICE: She was as surprised as you are.

BILL: Who is it?

JANICE: It’s not me, if that’s what you’re thinking.

(TOMMY has come in as if from outside and crosses the stage to his “room,” where a soft light comes up. As his parents continue talking, he stands by his bed, lies down, sits up, paces.)

I told her I had to tell you, because you’re her brother, and we need your help, and I really don’t like keeping secrets from you. But you absolutely can’t say anything. To anyone. Promise.

BILL: Who would I tell?

JANICE: I don’t know. Some moment when you want to be interesting. “My sister is a lesbian,” see how they react.

BILL: I won’t. I promise.

JANICE: Especially Jack. If Jack finds out, she could be in real trouble. It’s going to take two years to get the divorce and settle everything, and we have to be totally cool the whole time. It won’t be easy for any of us, especially Vera, who naturally wants to run off with her beloved right now, before she gets away.

BILL: How long has this been going on?

JANICE: Long enough. She’s sure.

BILL (Putting his head in her lap): Well, I’m glad. I think it’s kind of exciting. Don’t you?

JANICE: Poor Jack, though, even if it serves him right. Vera wants to raise Susan and the new baby with her friend. She wants the house, which is mostly hers. You may have to help her buy him out. Jack will have nothing. He’s starting to realize that. He’s losing everything, including Vera. Remember how he talked about her at his birthday party? She’s his prize, his pride and joy. She’s his symbol of success. She props him up. She makes him feel like a real person.

BILL: He’s making plenty of money.

JANICE: Yes, but he doesn’t get any satisfaction. Did you know he was transferred again? Another horizontal promotion. It’s company policy to keep the junior executives off balance. He must be completely freaked out. I hope he can control his temper, but if he finds out about her friend he may very well get custody of the children.

BILL: He’s their father.

JANICE: Of course he has rights. But Vera doesn’t trust him. He smacked Susan the other day because she spilled grape juice on her new dress. She doesn’t want to wear dresses. She wants to play soccer.

BILL: O.K., I hear you. I’ll give her a chance.

JANICE: It would be a kindness. And let Vera know you’re supportive. She’s afraid you’ll disapprove. She knows you’re a friend of Jack’s.

BILL: I just want her to be happy.

(TOMMY is now standing uncertainly outside their “door.” JANICE “hears” him.)

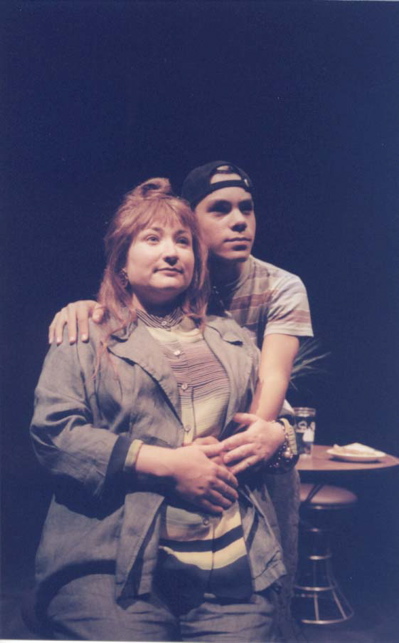

JANICE: Tommy? (No response.) You can come in, it’s all right. (He “enters” and hesitates at the edge of the light.) Come on. Come here. (He moves closer. BILL reaches out to him too, and TOMMY crawls across the bed into the circle of their arms, burying his face in JANICE’s shoulder, shuddering.)

BILL: There, there. What is it? What happened?

TOMMY (Muffled): Nothing.

JANICE (After a moment): Take off your shoes and tell us what you’re upset about.

BILL (Looking at his face): Did you fight?

TOMMY: No. I don’t fight. I run away.

JANICE: Good for you.

BILL: Sometimes you have to stand up to people.

TOMMY (Sitting on the edge of the bed, taking off his shoes): They’re stupid. I don’t want to talk about it.

BILL: People will take advantage of you if they think you’re afraid.

JANICE: Bill, please.

TOMMY: I’m not afraid.

JANICE: Tommy, I’m proud of you for running away, if that’s what you want to do. Your father doesn’t agree, but we don’t have to agree.

TOMMY: I can run faster than they can. Why should I fight?

BILL: Are they mad at you? What did you do?

TOMMY: No, they’re just bored. And boring.

JANICE: Daddy is going to put Suzy on the soccer team, isn’t that neat?

BILL: Not on the team. On the junior team. If she can keep up.

TOMMY: She’ll be good, you’ll see. I’ve been teaching her.

BILL: Oh have you.

TOMMY: She’s better than me. She pushes right past me. I can’t stop her.

BILL: That’s what I want from you.

(He gets up. They face off.)

JANICE: Can we talk about this? On the bed, please.

TOMMY: Mom.

JANICE: I can’t stand to have you two at odds.

BILL: He can’t quit. How can there be a team if people can quit?

TOMMY: Mom.

BILL: It’s not about soccer, it’s about learning to finish what you start. You made a commitment.

TOMMY: I didn’t want to do it this year. You forced me.

JANICE: That’s true.

BILL: I didn’t. I just explained why it was important.

TOMMY: You wouldn’t listen.

JANICE: Tommy, try to understand. Here, sit on the bed, both of you. (They do.) Feet off the floor. (They do.) That’s better. The thing is, your dad loves sports, and he loves you, and so it seems to him the most beautiful thing in the world to put those two things together. It’s not about those things he said, though they’re important too. You have to keep your promises and do what you say you’ll do. We’ve tried to set you a good example ever since you were a little boy. It’s not about that, though. It’s about love. Your dad is a very emotional person. He’s in love with the idea of you being some kind of soccer genius, and it makes him unbearably sad that it’s not going to happen.

TOMMY: He’s not my dad.

(The beautiful images of Desert Storm are still behind them.)

BILL: Yes I am.

JANICE: He is. I know, he’s not your biological father. You don’t look like him. You don’t have any of his genes. Maybe that’s why you don’t like to play soccer. Don’t laugh. Seriously, he’s your father because he took you on, not because he made me pregnant. It’s a more than biological connection, it’s a deliberate choice, and he has never failed to be there for you. You should be interested in that man in Mexico. He’s a very interesting man, and he can show you something about your future, and my past, if it matters. But he’s not in any way your dad.

BILL: Can I say something?

JANICE: Of course. Please do.

BILL: Tommy?

TOMMY (Reluctantly): O.K.

BILL: I was there when you were born. I was there when you stuck your head out, and you looked straight into my eyes. I’m sure you couldn’t see anything very clearly, but I saw you, and I loved you. It was the greatest moment of my whole life. Even before that, for months and months, I put my spirit into you whenever I made love to your mother.

TOMMY: Please.

BILL: Don’t be embarrassed. Your mother came into my life out of nowhere, pregnant with you, and I knew right away that this was who I was meant to be, her husband, your father. You don’t have to play soccer. You don’t have to run away from that. I’m not stupid. It’s true, I’m sad, but I’m not really sad, I’m happy because you’re you, Tommy. Truly.

(Tableau. Blackout.)

Scene 4

JANICE again speaks to the camera. No projection this time.

JANICE: He’s a good man. Like all of us he is formed and reformed by the culture we live in, this crazy time, but he listens to his heart, and he thinks. Reason isn’t perfect, but it works as well as anything. I don’t try to tell him what to think. You don’t have to be right all the time to be a good person. You don’t have to be perfect to be loved. So. Tommy is O.K. Vera is making her move. Bill loves me, but will he still be on my side when all my so-called secrets are exposed? I can hope so. I’ve tried to warn him, one way and another, and he’s taken it amazingly well. It’s because we make each other happy, and personal happiness is important to us both, each other’s and our own. But I can’t go on hiding, playing the loving wife and mother, however sincere I am, pretending this little paradise is the world, though I’m grateful that it’s mine, conspiring not to talk about any problem we can’t solve, or pain we can’t relieve, or hunger we can’t feed. How can we talk about compassion and play along with what this government is doing? The War on Some Drugs costs billions and props up monsters in South America. Congress is no friend of democracies. Two million Americans live in prison, disproportionately black. Mean-spirited politicians like Phil Gramm keep grinding down the poor, who are everywhere in rich America. Zimbabwe had to fire teachers to get a World Bank loan. I’ve saved myself. But who am I? What am I worth? My beautiful child is as impermanent as everything else. Life is a wisp of cloud. Does my ecstatic realization undo the suffering of one African with AIDS? Seriously. Does my recycling save the future from the radioactive waste my democratically elected representatives keep us manufacturing against all laws of God and common sense? I’m beginning to rave. I need to. I’ve been too good too long. They count on this. Domestic tranquility so infinitely sweet disarms our sense of outrage. Silence is the price of being left alone. Silence is the price of sanity. I think sanity is fury in a time like this. I thought I could put all that behind me, my youthful folly, as my mother and dad would say, but I can’t do it anymore. The situation isn’t better, it’s worse. The press is in their pocket now, owned by the same capital that grows from the wars it feeds on. Ever since Panama the writers have been locked up behind the lines, fed canned and calculated images to reinforce the storyboard. Bush’s propaganda was a joke. Kuwait is no better than Iraq, it’s just playing our game. And the missiles worked, sort of. Friendly fire was a problem, but not too many of our boys were killed. It was horrible, of course, they were miserable in the desert, but the fighting didn’t last long enough to destroy their minds, like Vietnam. Systems were tested, ordnance spent, so the factories have plenty of business, and we won, so we’ll do it again. There’s always an excuse for war if that’s what you’re set up for. And nobody does anything to stop it. The politicians are too busy hustling money for the next campaign. The students are setting up careers or opting out. The rich are protecting their profits. The poor are numb or in jail, or scrambling to survive. Everybody else is too busy to think, too busy communicating to have anything to say. Who’s left to make the revolution? And what are its aims? It isn’t enough to be happy and secure and perfectly equipped. How can I help the people who aren’t?

(Bright light suddenly comes up, for the first time, on the whole stage. BILL, TOMMY, and VERA are standing at the back and sides, looking at JANICE. She turns one way, then the other, then faces the audience. Blackout.)

Scene 5

TOMMY at the table. VERA brings him something to eat. The video camera has been taken away.

TOMMY: Arrested? Why? What did she do?

VERA: She hasn’t done anything bad. It’s something she did a long time ago, because she had to. They’ve been looking for her for years. But I think they’ll have to let her go. She’ll be all right.

TOMMY: It’s my fault.

VERA: She knew she was taking a chance. She was perfectly circumspect for fifteen years. Then she had enough.

TOMMY: They made me tell them my father’s name, even though she told me not to talk about it. I thought he would come and get me. But he said he didn’t have a son.

VERA: She knew it was all going to come down. It’s not your fault. I don’t know the details. She made a decision and this is what happened. She’s afraid Bill will feel betrayed.

TOMMY: What about me?

VERA: She thinks you’re old enough to understand.

TOMMY: What.

VERA: Not right away. It’s very hard to understand your parents even if they’re relatively simple, like mine. She isn’t. Neither am I, but she’s something else. I really admire her for the way she took care of her people, you and your dad and me, even with all this other stuff on her mind.

TOMMY: What other stuff?

VERA: Whatever. I don’t know. Whatever made them come and get her and take her away. I suppose it could be a mistake but I don’t think it is. She was ready. Your dad’s down there with her. I said I’d stay with you till he gets home.

TOMMY: You don’t need to stay.

VERA: I know but I want to. Can I?

TOMMY: If you want to. Aren’t you going to eat?

VERA: I’m not hungry.

TOMMY: Because of the baby?

VERA: No, because I’m upset.

TOMMY: About Mom?

VERA: No. (Pause.) Oh, she moved. Do you want to feel it?

TOMMY: That’s all right.

VERA: I’d like you to. This is your cousin, you should get to know her.

TOMMY: What do I do?

VERA: Give me your hand. (Takes his hand and puts it on her belly.) Now just wait.

TOMMY: I don’t feel anything.

VERA: She isn’t moving. Maybe she’s asleep.

TOMMY: Can’t you jiggle it or something?

VERA: No. There. Oo. Did you feel that?

TOMMY: I don’t know.

VERA: She’s very tiny but sometimes she kicks real hard.

TOMMY: Does it hurt?

VERA: No, not at all. I’ve never felt better.

TOMMY: Aunt Vera?

VERA: Hmm?

TOMMY: Why doesn’t my father want to see me?

VERA: I don’t know. I don’t think that’s it. He probably feels he doesn’t have anything to give you. His life went another way. He probably regrets it, but your mother went away, and he made another life.

TOMMY: He only has one arm.

VERA: Really?

TOMMY: And one eye.

VERA: I didn’t know that.

TOMMY: He’s black, did you know that?

VERA: What happened?

TOMMY: He didn’t want to talk about it. His wife told me not to bother him. I thought he might tell me this time.

VERA: Tommy, it doesn’t sound like you can help him. Maybe in a few years. He may need you when he’s old. I think you should stay here and finish growing up. Your mother wants you here, and so does Bill. He’s your real dad.

TOMMY: I know.

(BILL comes in with the video camera.)

VERA: Maybe you could help Suzy some more, too.

TOMMY: O.K.

VERA (To BILL): What happened?

BILL (Remounting the camera and hooking it up): They’re questioning her. They wouldn’t let me come in. They said it would be a couple of hours. So I thought I’d come home and get Tommy and go back later.

VERA: She’s talking to them?

BILL: Apparently yes.

(He turns on the video he has made of JANICE being escorted out of the house by two men in suits. He follows them very close, and the image is shaky, the background blurred. He goes right up to them as they are putting her into a car, but they turn him back. Cut to following the car through traffic. It stops at a federal building, where they park and take JANICE out. Cut to hallways inside the building. The camera follows JANICE and the two feds into an office where she is fingerprinted. Meanwhile the scene has continued.)

VERA: Shouldn’t she have a lawyer present?

BILL: She is a lawyer.

VERA: I don’t believe it. I don’t believe any of this.

BILL: She graduated from the University of Chicago Law School. She passed the bar. She was an assistant D.A.

VERA: What is she charged with?

BILL: I don’t know.

VERA: They have to tell you. You’re her husband.

BILL: I’m not her husband, apparently. She’s somebody else. The person I married doesn’t exist.

TOMMY: Where does that leave me?

VERA: You definitely exist, honey.

BILL: I don’t think she’s charged with anything. They said they just wanted to talk to her. And she said she wanted to talk to them.

VERA (Watching the video): It looks pretty funny.

BILL: I know. I thought they’d stop me, but they didn’t.

TOMMY: Are they hurting her?

BILL (Putting his arm around him): No, really, I think she’s O.K. I think she’s doing this on purpose. They don’t want a trial, she said. They can’t do anything awful. I’m a reporter. This is the United States.

VERA: Who are they?

BILL: I don’t know exactly. They’re feds. I can find out. It’s the federal building. I think they came out from the Justice Department in Washington. It’s political.

TOMMY: I’m scared.

VERA: We’re all scared.

BILL: Don’t be scared. This is America. This isn’t Argentina, or China, or Iran, or Sudan, or Colombia.

(On the video JANICE is photographed holding a sign that reads SHARON MURPHY, 7-29-91.)

VERA: Sharon Murphy?! She’s Sharon Murphy?!

BILL: So?

VERA: The house that blew up. The black revolutionary cult. The two young D.A.s that disappeared. Years ago, in the seventies. You must have seen it on the news. It went on for weeks.

BILL: I don’t watch tv.

VERA: She didn’t look like our Janice. Her hair was cropped short, like Joan of Arc.

(On the video JANICE turns to the camera and says, “Tell Tommy I’ll be all right. Tell him I love him”—we can read her lips.)

TOMMY: I love you, Mom.

(JANICE says, “I love you too, Bill.” Then she is taken into another room, the door is closed, and the “screen” goes “blank.” Blackout.)

Scene 6

TOMMY is bouncing on a trampoline upstage of the table. Beautiful panoramas of American scenery are projected on the wall behind him, lyrically moving and dissolving. He bounces steadily for a while in a relaxed rhythm. Then he does a series of tricks—twists, layouts, somersaults. Then he just bounces, higher and higher. Fade out.

Scene 7

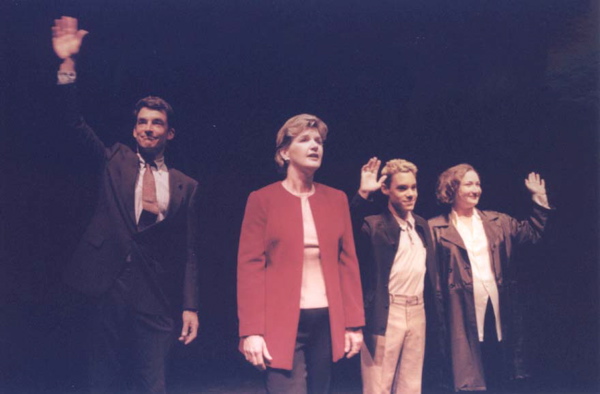

The present. JANICE is sitting in the chair, center, speaking earnestly to the audience. Her hair is short and turning gray. The camera is gone. Behind her is projected an image of the American flag, sunlit and waving in a fresh breeze.

JANICE: I’ve been reading history. It’s different from what I learned in school. Everything goes much further back. Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard is like the first army we know about, five thousand years ago in Sumer, which started as a royal bodyguard. There has been an international market in advanced military technology since the invention of the chariot in the second millennium B.C. But that’s no excuse. The United States spends more on “defense” than all our NATO allies combined, five or six times as much as either Russia or China, several times the entire GNP of prewar Iraq. We’re so rich that it hardly seems to matter, and the military keeps out of sight. But it warps our morality and economy, and it still wants more. Nothing will be enough if we keep trying to dominate the whole world.

(Stands.)

I suppose I was naive to think I could stop war with my opinion, no matter how dramatically expressed, or counteract racism by making bombs. But I had to do something, and I still do. It’s my nature to act. Some of the people I used to know have come a long way in the world, and they’re urging me to run for President. I think I’ll do it. People are ready for somebody like me. The major parties are doing serious damage. This could be a glorious time for humankind, we all know that, but politics as usual is threatening the basic well-being of the world. People are sick of being scared. Nuclear disarmament is the first priority, and general demilitarization. The military will fight me, but if they get me, somebody else will take my place. Beyond that, I’ll just do what’s needed. It’s pretty obvious. House and feed the homeless and the poor. Make school interesting. Eradicate the prison industry. See to everybody’s health, starting with prevention and good nutrition. Restructure world trade to protect the environment and benefit people everywhere. Level the field for all the races on all the continents. Legalize hemp and marijuana, and criminalize the manufacture of junk food. Mock the media. Redistribute the wealth. Favor people, not corporations. Tell the truth. That would be a change.

(Sits.)

They charged me with conspiracy, and I beat the rap. I wasn’t there when the bomb went off. I didn’t make it, I was just friends with the people who did. It’s true I had poured blood in the draft board files, but by then I was playing it straight, and the romance was over, ironically. Still, it seemed safer at the time to disappear. It’s a relief to have it all come out, and the past few years have been the best yet for me personally. But the social injustices keep piling up and the wars have gone right on—Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, Serbia. We’re still attacking Iraq, still trying to starve them out. It’s medieval siege warfare. People are starting to think, though, thank God. Tommy is twenty-five and doing great. He took time off from dancing in New York to work on the shadow conventions and the Nader campaign. Bill and I have been going to the Friends meeting. Bill writes about the World Bank and the IMF for The Nation, and he’s helping me with my platform. We have some good ideas about the economy that I won’t go into now, how to move it back toward parity. Oh, and Vera and the girls are doing fine, and Jack treats his new wife with respect. They’re all joining my campaign too.

(The others join her in the light.)

We’re so lucky to have each other and share this precious time on earth. I’m counting on you to help us spread the blessings to everyone.

(The light brightens for bows as they smile and wave to the audience in front of the billowing flag.)

Copyright © 2000. All rights reserved.

Reviews

Santa Barbara News-Press, November 30, 2000

by Philip Brandes

A quick rabbit punch to the soft underbelly of complacency, Michael Smith’s new play, “Dogs Bark All Night,” intelligently tackles the conflicted path we all face in balancing personal fulfillment and social responsibility.

By way of full disclosure, Smith is a colleague who writes for the News-Press, but he also has an extensive history of professional involvement with local theatre as a playwright and producer. His commitment and seriousness of purpose are never in doubt in this production.

The touchstone protagonist for Smith’s ethical meditations is Janice (Laurel Lyle), a former ’70s radical who has spent the last 15 years on the lam, reinventing herself as a housewife. “Domestic tranquility disarms our sense of outrage,” she readily admits.

Yet despite her efforts to focus on her narrow patch of middle-class utopia, by the play’s opening in 1991, Janice finds her social conscience increasingly goaded by troublesome world events, including the Gulf War, a deteriorating environment, and the politics of hypocrisy. This onslaught of problems is elegantly and effectively conveyed via Nick Vincent’s video montage during Janice’s impassioned opening monologye, which culminates in her decision to reveal her past and face the music. In guiding us through very step in Janice’s decision, Lyle’s assured performance is notable for its clarity and precision.

Janice’s disclosure comes as an understandable shock to her husband, Bill (David Brainard), who realizes that after all their years together he still doesn’t know his wife. Initially clueless, critical, and less than understanding, Bill is comically buffeted by changes fast and furious.

In addition to his wife’s scandalous past, he also has to contend with the life-changing decision by his pregnant sister (ClaireMarie Mallory) to leave her abusive husband—for another woman. And, of course, there are the ongoing tensions in his attempt to be a good father to Janice’s son (Steven Gonzales).

Yet despite his emotional floudering, Brainard’s Bill emerges as a character of great strength—an admirable affirmation of the potential for growth and accommodation to life’s vicissitudes.

The play’s signature strength is its clear articulation of political and ethical issues through direct address to the audience and through arguments between the characters. However, that structure also risks turning human relations into polemics. The biggest challenge facing director Maurice Lord is to personalize often abstract dialogue with natural conviction.

There are some lapses or exaggerated artifice in this regard, particularly in some of the exchanges between Janice and Bill during the play’s middle scenes. Since props are minimal, mood, setting, and character are heavily dependen on some wittily understated but suggestive costumes by Kimberly Galloway and evocative lighting by Smith.

By the play’s end, the capable actors find their way to a satisfying emotional resolution—with an upbeat ending, no less. Whether you buy the optimism or not, Smith’s call to activism now seems uncannily prophetic and right-on-target in light of the deep-seated problems exposed by the ongoing election turmoil.