“Prussian Suite”

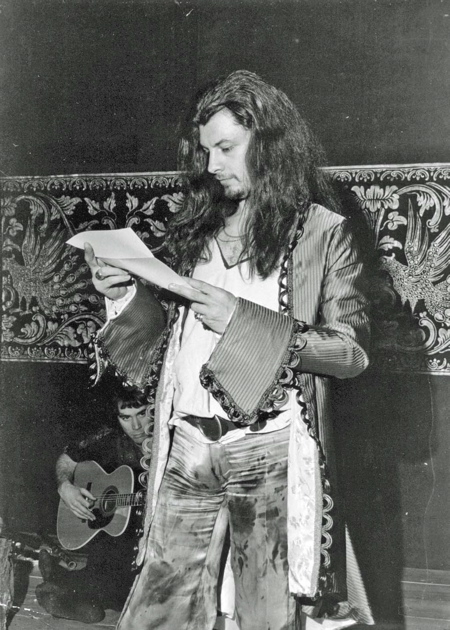

Ken Wollitz, a superior recorder player and lovely man whom I made music with during a dark time, introduced me to the story of Frederick the Great, a musician, composer, intellectual, friend of Voltaire, as well as, in his maturity, a relentless militarist who made Prussia the dominant force in Germany. (Ken and I played a sonata by Frederick in a concert we gave to inaugurate my new harpsichord at a West Side church in May 1973.) I had a slot at Theatre Genesis in early 1974, and I wrote “Prussian Suite” for it, basing the play on a crucial episode in Frederick’s early manhood.

His father, the King, hated everything French and regarded Frederick’s sensibility and taste for ideas and beauty as effete. Frederick had one friend, Katte, a young captain, with whom he could be himself. His father became so oppressive that the young prince resolved to run away to France and enlisted Katte to help him plan the getaway. His sister, Wilhelmina, advised him against it. She was being married off to an insignificant margrave, although she had an opportunity and inclination to marry the future king of England, and she needed Frederick’s help in changing the King’s mind. But her brother was too caught up in his own drama, which fell out badly. He was caught at the border, wearing a red coat so the French would recognize him, and brought back to the palace. To teach him a lesson, the King had Katte executed in the courtyard outside the Prince’s window. As the play ends, the King, crippled with gout, foresees his own funeral, and Frederick comes into his power.

In truth I was burned out at this point, weary of being a critic, disillusioned with the downtown theatre, sick of New York—which was in fact going into a serious slump. I was in a new relationship with a woman, Michele Hawley, who had come east from Denver to live with me in Park Slope. My life was changing, and this was the last play I did in New York for many years.

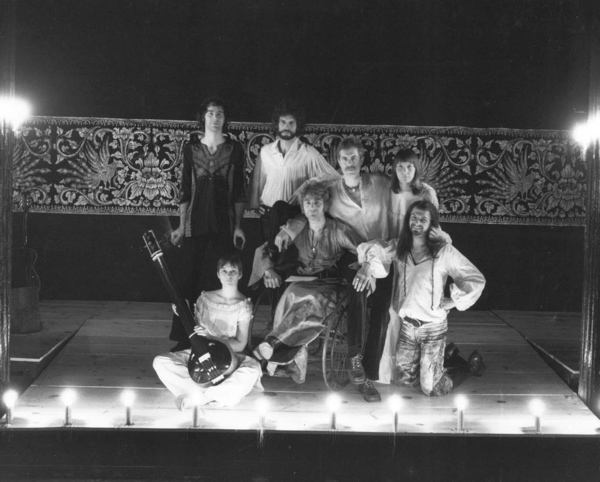

The cast and musicians of “Prussian Suite”: clockwise from top left, John Smead, Charles Stanley, Michael Smith, Georgia Lee, Jimmy Centola, Ondine, and Michele Hawley

The cast consisted of Ondine, Charles Stanley, and Jimmy Centola, leading light of the Hot Peaches, a glitter-drag troupe I had reviewed for The Voice. When the first two actors I cast as Wilhelmina did not stick, Georgia Lee (Hadler) stepped in and gave a lovely performance, though I had little attention to spare for her. Ondine was potentially wonderful as the King; he had the gravitas and attitude, if I could keep him from dissipating it in camp. He played the last scene with full feeling once in rehearsal, scared himself, I think, and never really did it in performance. Charles was running himself ragged, doing another play simultaneously at La Mama, exhausted and strung out, trying to be efficient and conserve his energy. Ondine was off speed, but he and Charles were both drinking to excess. Jimmy felt out of his element, as he describes eloquently in his wonderful journal (scroll down). He was sexy and charismatic, and I loved his genuineness and sincerity.

The play is structured in a series of short scenes, and I decided each should be played twice, except for the first and last, like a French suite. It would have been simple to let Charles be the Rising Sun and Jimmy be Katte (also called Cat); instead I imposed yet another layer of artifice on this already obscure play by having them switch roles on the repetitions. This was probably a mistake and made things harder for everyone, but I was trying to make some point about the distinction between person and social role. Charles’s Prince was cold and precious, his Katte slyly seductive; Jimmy’s Prince was nervous and repressed, his Katte a slick hustler. All these interepretations were valid to me, but the doubling was confusing to the audience, and I wonder how much of the real story came through. It is a powerful story, of a son coming of age, the passing of power from one generation to the next; that was surely my personal interest in writing it, as I was moving toward marriage and children of my own. There is also a gay subtext, of course, but it is completely subsumed in the deeper theme.

The production was lovely, if I do say so myself. John Smead, a guitarist from Chicago who had collaborated with Charles, created and performed a beautiful score that was virtually continuous, with me playing the harpsichord and Michele playing a tamboura drone throughout (except for one scene). I had never played music that was not written out, and John was patient in teaching me to improvise to his changes. He and I also played recorders at times and punctuated the action with the percussive sound of a hatchet chopping into a stump and a tubular chime. I designed an elegant wooden platform stage, backed by a black and gold painted cloth I had brought back from Bali, removed the shades on the windows so the streetlights in the treetops could be seen outside, and lit the play entirely with candles: it took thirty candles to make it bright enough. The stage was raked, which made it hard for Ondine to control the antique wheelchair in which he played a major scene. Skye Vermont made two beautiful red brocade coats.

WBAI recorded and broadcast the play. Unfortunately we had inadequate studio time, the harpsichord and guitar were not in tune, and the balance was less than ideal. But it is pleasing that a record exists.

Production Credits

“Prussian Suite,” with music by John Smead, was first presented 31 January 1974 by Theatre Genesis at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bouwerie, 10th Street and Second Avenue, New York, under the author’s direction with the following cast: The Rising Sun and Cat, Jimmy Centola and Charles Stanley; Wilhelmina, Georgia Lee; the King, Ondine. The musicians: Michele Hawley, tamboura; John Smead, guitar, shakuhachi, suspended washtub bass, and chop; Michael Smith, harpsichord, recorders, and chime.

“Prussian Suite”

The Rising Sun (Frederick); His Sister Wilhelmina; His Friend Cat; His Father, the King; Musicians

Bare platform stage.

Candlelight only.

Musicians on the stage. Music when audience enters. Drone continuous. Other music with the drone between and with most scenes.

It is intended that each scene, save the first and the last, be played twice, in the fashion of an 18th-century musical Suite (i.e., Scene 1, Scene 2, repeat Scene 2, Scene 3, repeat Scene 3, etc.). The repeats, which follow without pause or break, may give the players occasion for embellishment.

The characters and events are drawn from the life of Frederick the Great, 1712-1786.

1: Sweet Children

Rising Sun alone, sitting reading.

RISING SUN: I feel myself falling through darkness, this floor falling down and back through space. If I stop myself from falling I’ll have nothing to sit on. This little sphere of light, the sounds of other worlds passing, what will be, what might have been. Only this night. I am alone, it’s history crowds me round. What do you want? Why me? The phone rings, I answer.

WILHELMINA (from the dark): Let it ring.

RISING SUN (still reading): Hello?

CAT (from the dark): Hello, Prudence?

RISING SUN (politely): I think you have the wrong number.

CAT: Oh, sorry.

WILHELMINA: Who was that?

RISING SUN: “Hello, Prudence?” He said, “Hello, Prudence?”

WILHELMINA (entering in nightclothes): Are you coming to bed?

RISING SUN (still reading): “TPG’s production results in a disassociation between drama-script and theatre-performance, as well as a further dissociation between theatre and performance. The model can be re-drawn into utterly discrete units, each of which may be in opposition to one or more of the others.”

WILHELMINA: What are you reading?

RISING SUN: Who was that?

WILHELMINA: It’s like walking on water here.

RISING SUN (looks up): What does that mean?

WILHELMINA: Is something the matter? You’re angry with me. You’re really angry.

RISING SUN: I don’t dare move. If I move my body I’ll pass out or throw up or fall aparat.

WILHELMINA: I’ve already been asleep. It’s late. Come to bed.

RISING SUN: I have to get up early. I have a million things to do.

WILHELMINA: Don’t think about them now. Let your thoughts go right on through.

RISING SUN: Come here. What’s happening to you, my love?

WILHELMINA (sitting beside him and then in his lap): Don’t be angry, sweet prince my brother. Time won’t go faster. I know. Let me tell you a story about an eldest daughter for an eldest son. Happy is he whose brothers… I can’t remember the rest.

RISING SUN (putting book away): The story.

WILHELMINA: Don’t pity me. Don’t be angry with yourself for being stronger. I could be Queen of England but I’m marrying a nobody, for somebody else’s spite. The story is about a princess who loves her brother more than any other man. The father is cruel to them both, from choler. He will be king, but she will never be his bride. They meet in his apartments one more time before she goes. He could be anyone. But he isn’t. Everything happens for reasons of state. Nothing has the desired effect anyway. They are victims of fantasy causality. We are alone, the others are asleep. The guards outside our door are only guards. I wish I were free. Something else could happen but it won’t, I’ll have to go through with it, and I’ll be “fine.”… On a summer day, woods wet from rain and steamy in the sun, my shirt clings to me. I run for the cool delicious surfaces. I come out dancing in the meadow, sunstruck, I fall down beside you on the great cloth. You are naked, brown, your flesh hot, swollen. You lay aside your book. We talk. I am breathing fast, as if I were excited. We can see the village far below. We see a child coming toward us far away, a boy in purple shorts and moccasins. He calls but a high hot wind is in our ears. We hear nothing but each other and the breeze in the grass and the cries of birds. You talk of memory, when we were children here. Those birches were young and smooth; now their skin is tattered, and the old one broke last winter from the ice. Some are dead who saw this sight, and some are yet to come. The boy comes closer. You make no move. I am crushed by the sun, my limbs have no power of their own. Far below us the church bells ring. If I am to be saved it must be now. He will be king, and I will be a country wife, and these sweet children never see again. I’m not surprised, I’m not surprised.

(Music)

2: This is German

King alone.

KING: When I was a boy I believed in the power of power. I believed in what I was told. My father was proud. He made himself king and so made me king, and so I believed, and so I am. When I was a boy I believed in the power of power. I believed in what I was told. My father was proud. He made himself king, and so made me king, and so I believed, and so I am. I’m not acting this way naturally. Everything I do is deliberate. I make this my nature, to be what I show myself to be. And so believe. No one is fooled. I know I’m foolish, sometimes or in sum. I know the people hide from my hand and mock my physiognomy. I fear myself but so am made, wild creature that would be civilized, wind-up king that would be brought alive by love. So be it. I’m not raving now, but in my heart mad mischief gnaws and thrashes. My days are parceled out in words. I don’t love words. I have to use them. I’m one of the word people, trying to make them do some good— My playthings are soldiers six and a half feet tall. I’m a little fellow, but energetic. My Longfellows dress up for me and march in unison. Our cousin Russia gives me one hundred of them every spring. When somebody comes to visit I put them on parade and shoot off the cannon. That says something. My nights I spend smoking and joking with my friends. They keep me amused and don’t ask for much attention. The Rising Sun hates my tabagie. He’d be French if he had his way. But the French are rich. I speak French myself. This is French. But I speak German too. This is German. I speak only German to the Rising Sun. He must learn!

(Music)

3: Dull Attitudes

Rising Sun, Cat.

RISING SUN: What is it you like about me? Why do you love me? I see that you do, with a generous frankness, while I withhold myself, from habit or from stinginess, from education and fear, from poverty of spirit. And still you love me and esteem me, not condescendingly as I deserve, but truly. While I give myself to no one or to all, you single me out and embrace the world in the largeness of your natural heart. I am shamed by you, silenced, turned judge against myself, and so compound the guilt. Dull attitudes! I am your prisoner, yearning for your love.

CAT: It’s too dramatic. He’ll think you’re putting him on.

RISING SUN: But I mean it!

CAT: I know you do. Don’t doubt me!

RISING SUN: I don’t!

CAT: Stop protesting your sincerity. Once and for all, I have perfect knowledge of your good intentions.

RISING SUN: That doesn’t mean very much.

CAT: Oh stop! I’m not your father. And it’s too confused. It didn’t make any sense. Either you know he loves you and you’re trying to get the upper hand, using insecurity as a weapon. Or else you know he doesn’t love you and you wish he did.

RISING SUN: Well, it’s not all about him.

CAT: Who, then? Yourself?

RISING SUN: Be my father for a minute.

CAT: O.K. I am your father. Get down on your knees, cur, sniveling worm, prune pit.

RISING SUN: Not prune pit.

CAT: Anyway, it’s not a matter of paranoia. He’s really crazy. You have to get into the logic of his madness.

RISING SUN: I don’t know if it has any.

CAT: Then it’s hopeless. (Pause) Do you feel that way about me?

RISING SUN: No, I know how I feel about you. I mean I know how you feel about me. Oh never mind.

CAT: Why do you snivel and whine so?

RISING SUN: Habit. I am the slave of habit. I know I do it.

CAT: Why do you keep talking about slaves? Do you want one? Who are you, anyway?

RISING SUN: How do you mean? Who are you?

CAT: I am your Cat. You know me. You know my moods, my fantasies, my personality. You know what I look like on good days and bad, when I first wake up, when I’ve smoked too much, when I’m obsessed with sex, when I haven’t come in out of the rain. Sometimes I’m friendly, sometimes I want to be left alone. I don’t actually go away. If I do, you come find me and bring me home, and I come. What more do you want from a cat?

RISING SUN: I don’t want to be the master.

CAT: Well, you are. Hail to the rising sun.

RISING SUN: This is intolerable.

CAT (As King): Lick my boot, fruit. Lay your filthy French tongue on my tough German leather. Learn to love the taste, swine, and someday maybe you can put them on. If I don’t kill you.

RISING SUN: Why do you treat me so bad? You know I love you.

CAT: You love yourself. Why don’t you kill me and end this farce?

RISING SUN: Are you suggesting?—

CAT: You scheme with your mother for a foreign bride. You’d have your sister queen of England. You borrow from all the embassies against my death. You wear French wigs because you know I hate them, and you’d rather laugh and talk philosophy with your alley cat than drill my Longfellows.

RISING SUN (Laughing): Only the last is true.

CAT: It’s all true.

RISING SUN: Of course it’s true, mais je suis…moi-meme. I’m just dealing with the situation.

CAT: You’re miserable.

RISING SUN: Nonsense. I’m happy.

(Music)

4: Love Scene

Rising Sun alone. Cat enters, stands waiting.

RISING SUN (After a long pause): Hello, Catkin.

CAT: Your highness.

RISING SUN (After a long pause): Splendid. The day.

CAT: Yes sir.

RISING SUN: Relax.

CAT: I am.

RISING SUN: Good. (Pause) Have you spoken to anyone?

CAT: No.

RISING SUN: Good. Did you get the coat?

CAT: Yes.

RISING SUN: Let me see it.

CAT: I’ll get it. (Goes)

RISING SUN (While he’s gone): I have too much to learn. Ever since I was seven I’ve been getting up at seven every day and studying and learning all day except for two hours with my father the king at lunch and two hours in the evening. I feel like a beginner. I’ve never done anything. I know nothing. And I look for help from people who know even less.

CAT (Returning with red coat): I have a letter for you from your sister.

RISING SUN: Did anyone see it?

CAT: What?

RISING SUN: The coat.

CAT: No.

RISING SUN: Good. (Tries it on) How do I look?

CAT: Spectacular. You look like visiting royalty.

RISING SUN: That’s the idea. I have to look like the crown prince of Prussia when I get to France. They’ll never believe it’s me if I dress like myself. Let me see the letter. (Cat gives it to him. He reads.)

WILHELMINA (Off): Beloved brother, you must be strong. Our fiendish revered father king in Prussia will marry me to the Margrave of Nowhere and I’ll vanish from the stage of history. Invitations are being sent out now. All the courts of Europe will know our want of simple dignity, and pity and look down upon us more. Our cousin Hanover and England is rightly to my liking and your advantage, and still available. We must act at once, or the tyrant will have his way with us. You are next! Katte will tell you more.

RISING SUN (To Cat): Sometimes a feeling comes into my body, a pleasurable slowly throbbing aching in the loins, an independent energy hungry and wanting out. I am not to know the satisfaction of love’s body because of a disease I shamefully contracted in my bitter youth. I speak of this to no one. Records of the surgery have been destroyed. Memory is readily confused, and speculation springs up anyhow. My father knew and was made the more cruelly angry by this failure of his line. And so I am obliged to flee. I ask your help and private sympathy.

CAT: I really love you, my prince. I always have.

RISING SUN: I know you do. I don’t know why.

CAT: Don’t start that. Just lie back and enjoy it.

RISING SUN: I do. I’m basking in it.

CAT: Don’t be afraid. (Pause) I know you don’t know how to act. But you don’t have to do anything. (Pause)

RISING SUN: I can hardly stand it. (Pause)

CAT: The story of the deer in the forest. (Thought-by-thought) In winter they don’t feel cold. In the dark they don’t turn on a light. They don’t know what anything is. They do know each other apart. They know what to do. They are not confused. They do think slowly: they wait for clarity to come. The world around them never pauses in its changing. They don’t have houses. Every day is different.

(Music)

5: “Don’t Do It!”

Rising Sun, Wilhelmina.

WILHELMINA: Do you think I’m getting terribly plump.

RISING SUN: I haven’t thought about it. No, of course not.

WILHELMINA: Do you think I’m pretty?

RISING SUN: Sometimes.

WILHELMINA: Often?

RISING SUN: You’re pretty when you’re happy.

WILHELMINA: Sorry. (Pause)

RISING SUN: Are you getting unhappy?

WILHELMINA: What do you think? You haven’t talk to me in days.

RISING SUN: I know it. I’m sorry. Listen, can you keep your head together for a little while longer? If you fall apart now it will make a real mess.

WILHELMINA: It couldn’t be any worse.

RISING SUN: We all say that. But is it true?

WILHELMINA A: What’s going on?

RISING SUN: I have to be my own man.

WILHELMINA: What’s going on? Are you doing anything about saving me?

RISING SUN: What can anyone do?

WILHELMINA: Marry Louise to that sweet Bohemian archduke. She likes him. I’m not suited to this role. We’ll give them their wedding, but don’t make me be the bride.

CAT (Entering): Did you tell her?

WILHELMINA: Oh I’m saved!

CAT: What?

WILHELMINA: What?

RISING SUN: No.

WILHELMINA: He hasn’t told me anything. Freddie, do something! My life is about to be ruined!

CAT: Tell her. (Exit)

RISING SUN: Can you keep a secret?

WILHELMINA: Will you stop it! Stop playing with me! I’m not your mouse!

RISING SUN: Wait—

WILHELMINA: What’s going on?!

RISING SUN: How did I get into this?

WILHELMINA: Tell me!

RISING SUN: Calm down first! The whole point is not to lose your composure. Otherwise it’s all off.

WILHELMINA: What it?

RISING SUN: Well, I’m going into exile. I’m going to slip away before we get to Halle and cross over the Rhine into France. I have a red coat I’m wearing as a signal. Then I’ll take refuge with our cousins in England.

WILHELMINA: My God! When is this to happen?

RISING SUN: We leave tomorrow. I will reach the Rhine in about ten days. Katte will stay here with a casket of my papers and money to bring to me in London.

WILHELMINA: You’re mad.

CAT (Entering): Did you tell her?

WILHELMINA: This is crazy. I’m the one being sold into slavery, and you’re tipping off to England. You’ll never make it. You’re too disorganized.

CAT: We don’t need negative thoughts. We need help.

WILHELMINA: Don’t do it!

(Music)

6: Interlude

Rising Sun, Cat.

CAT: I was really nervous the first time I met you.

RISING SUN: So was I.

CAT: That’s ridiculous.

RISING SUN: Don’t call my feelings ridiculous.

CAT: But I had reason.

RISING SUN: I was taken over by it. I was embarrassed but I couldn’t stop acting that way.

CAT: I could see you were uncomfortable.

RISING SUN: Why didn’t you come to my rescue?

CAT: But that’s fantastic. You’re the crown prince.

RISING SUN: I feel trapped in it. You couldn’t forget it. You kept talking about it. Do you think I need to be reminded? It was horrible. I thought I’d never see you again.

CAT: I don’t see why it mattered.

RISING SUN: You mean you’re nothing special?

CAT: Of course not.

RISING SUN: Yes, and I was intimidated. I had seen you, after all.

CAT: You need to get over this feeling of hopelessness.

RISING SUN: Yes, Cat.

CAT: Am I so beautiful?

RISING SUN: Yes, and so self-possessed. I was leaning forward, yearning, searching your soul with my eyes. You were relaxed, taking it all in. I was afraid to take my eyes off you for fear you’d see I wasn’t there.

CAT: Poor king.

KING (Storming in): Over my dead body call him king before I die!

CAT: Sire, I meant no disrespect.

KING: I want no comforting or friendship for the rising sun. Prepare yourself a nook in heaven, better, if your filthy French manners don’t send you down the other way. Maybe Death will choke on your lovely hair, but maybe not.

RISING SUN: Father—

KING: Mark my words! (Exit)

CAT (After a pause): Now I’ve gotten you in trouble.

RISING SUN: No.

CAT: I hope you’re over it.

RISING SUN: Who am I now?

CAT: Do you want me to be your father?

RISING SUN: That’s not what I mean. Oh never mind.

CAT: Do you want to play chess?

RISING SUN: All right.

(Music)

7: All Is Lost

Wilhelmina alone, reading a letter.

RISING SUN (Off): Sweet sister, all is lost. We are discovered. The red coat has been confined. I am confined. My Cat is in the most immediate peril. Tell him to take from the silver in the casket what he needs and fly to England. Later he may return with no dishonor if only we ourselves survive. The letters had better be destroyed. Destroy this letter first. Your own dear life I will endeavor to repair when once I am myself. Sweet sister, nothing can save us from this present time, only it will pass. Yours in jeopardy—

KING (Bursting in): What’s that? What are you looking at?

WILHELMINA: My lord—

KING: Give me the letter.

WILHELMINA: Sir, it is private matter between myself and an intimate friend.

KING: I am more intimate. Give it here.

WILHELMINA: Sir, you make much of nothing.

KING: You hesitate to obey? Can I believe this wenchish flirtery? I am not king in jest. You must obey!

WILHELMINA (Runs to exit, blocked by King): Let me go! I am not to be tortured more!

KING: I will kill you if I must. So you know. Don’t make me angry. Give me the letter. (He gets the letter, throwing her to the floor, and scans it.) I knew it!

WILHELMINA: It’s nothing, sire, it’s a jest we make between us. I am lonely when he’s away, and he writes me stories for the idle day.

KING: I have him in irons. I know what’s a story. You are his confidant and accomplice. You’d have me give you England and you scheme to take away my rising sun.

WILHELMINA: You do not love him—

KING: What do you know of love? You think yourself in love with a prince you’ve never met, loving in fact his future power. Power can’t be loved. You say you love your princely brother but encourage him in lunacy. Exile in England? In a scarlet coat? You’re fools! But hush, someone approaches. I’ll hide me here behind the arras and overhear. Betray my presence and your punishment is doubled.

(Hides)

CAT (Entering, in red coat): What’s the news?

WILHELMINA: How do you address me?

CAT: You have a letter. What does he say?

WILHELMINA: Remember whom you speak to.

CAT: Is he got away? What am I to do?

WILHELMINA: Too late! Listen to me!

CAT: What?

WILHELMINA: How do you address me?

CAT: Your highness.

WILHELMINA: And who are you?

CAT: Your humble servant. Your brother’s cat.

WILHELMINA: And the king’s mouse, I fear. The sun says all is lost. He says to take the silver and fly. Burn the letters. Quickly! Now!

CAT: I don’t understand.

WILHELMINA: Go! Go away! Now!

(King with a terrible groan falls to the floor behind arras. They rush to him and drag him forth.)

KING: Oh! Ah! Curse this pain that curses my foot. It offends me and I’d have it off. But everything offends me. My daughter the virgin lover offends me. This frissy plum underling offends me with his fancy liberty. The rising sun offends me most of all: he’s dragging at my life and banking on my death. We’ll see who dies! Here, help me up.

WILHELMINA: Cat, go while you have the chance.

KING: He won’t. You’re not the one who gives commands.

WILHELMINA: Save yourself! You can’t save me! The rising sun will save himself!

KING: Captain, please remain. And as for you, my saucy child, I’ll hear no more of what you want and what you think you’re due. You are the daughter of the state and the state is me, and I can’t release you from our will nor will be bent. Thanks both.

CAT (Kneeling): Your majesty, no one wishes you ill. It is for lack of love that the prince must flee, or lack of love’s conveyance, for love of thee, to spare thy wrath and pain.

KING: Nothing is spared for him or me. (Raises his stick; Cat cringes.) Why do you hide?

CAT: We are afraid.

KING: Afraid? Afraid? (Beats Cat) You must love me!

CAT: I do! We all do love you!

WILHELMINA: Stop it, father, stop it!

KING (Beating him): Love me! Love me! Love me!

(Music)

8: Farewells

Rising Sun

A

RISING SUN: In a moment they will bring him to me for a last farewell, as if we were lovers, as if one of us was already dead. He is to be beheaded in the courtyard just outside. My father has locked me in this room whose only window looks out on my only friend’s death. I would rather die. But my father will not kill me yet. He spends instead the sweet life of this honest boy who loves me. To teach me a lesson. Well then I will learn.

CAT (Brought in): It is an honor to die for such a prince.

RISING SUN: You’re mad. That’s an insane thing to say.

CAT: I have no choice. No more do you. Our parents make us and the movements of the planets make our lives. We can do nothing. We must amuse each other and improve our selves. I have given myself to you.

RISING SUN: Thank you. I accept.

(Cat taken away)

(Music)

B

WILHELMINA (Entering): I’m so sorry for what’s happened.

RISING SUN: Thanks, sister.

WILHELMINA: And happy to see you well and free again.

RISING SUN: Free? But I am well, if by well you call me strong. And how does the margrave keep you?

WILHELMINA: Why are you so cold?

RISING SUN: Am I? Yes. I find my memories of you are only memories of myself with your eyes on me, when I’d come upon you playing and shortly join your game.

WILHELMINA: I wasn’t always playing.

RISING SUN: Was I? Can’t say. It’s over now. Now I’m returned and you’re away. I wish you well.

WILHELMINA: Can that be all you have to say? Many’s the nights I lay with you in prison. The same thoughts turned and burned in me, taking us one by one away. The footsteps echo in the hall. A key turns in the sleepless lock.

RISING SUN: Thanks, sister, for your dreams, but I have my own. I lay in the cell alone. And now, adieu.

WILHELMINA: Not like this!

RISING SUN: How, then? Does the final gesture make the whole effect? Kiss me, then, and go.

WILHELMINA: I’ll not.

RISING SUN: Someday we’ll have a moment for a moment’s grace again. Not now. And nothing will be as it was. We are deluded when we wish. And so let be.

WILHELMINA: I too have changed.

RISING SUN: I’d hope so—

WILHELMINA: Let me in and I’ll show you more.

RISING SUN: Leave me. Please. I can’t think of you just now.

(Music. She goes.)

9: Sunrise

King in wheelchair, Rising Sun kissing his gown.

KING: Am I not blessed to own such a reverent son? (To Rising Sun) It is a life of hardship, of ceaseless, thankless work. This is what I leave you. This is what you must embrace.

RISING SUN: I embrace you with all my heart.

KING: I wanted to retire. Let someone else be king. We’d move to a cottage. I’d keep a garden. Your mother would keep the house. Wilhelmina and her little brother would play music for us after supper. She’d go to the conservatory and he’d grow up to be an officer, noble and tall. (Rolls around) Wake up, I’m dying! But you weren’t ready, and we do what we are. We are not French.

RISING SUN: I know. But I love the French intelligence.

KING: As a friend only, never as yourself.

RISING SUN: Am I ready now?

KING: Almost. (Rolls around) Wake up, come here, I’m dying! No one can teach you about yourself but what you know. Think on it. Ah! My sweet Christ take me to your side! Show me your diamond throne! And keep no court—we can’t afford it. Only keep my Longfellows in memory of me. Don’t spend too much on the funeral. Don’t worry about your sister. Keep several separate secretaries and don’t trust anyone, least of all him who seems to trust himself. Keep the only key to the cabinet in your pocket. Where is everyone? Ah!

RISING SUN: We are alone. The palace sleeps. The sudden night takes from the towers the flags and then the heavy stones themselves. They fall to express their gravity. So the weight of myself falls from thee to me. And still we are alone.

KING: Ah!!!

RISING SUN: There is no crown to make me bow. And still I bow. I must be bowing to myself.

KING: No one. I’m going back to bed. (Exit)

RISING SUN: We are alone. So I am to be me. Alas, poor who I didn’t get to be. When I am almost twice my father’s age some men will curse me and others cheer when I pass hatless on my white horse. The old man hasn’t missed a day of work. He’s working for us that we may work for ourselves. (Chimes) Let the Longfellows march for the funeral and then be disbanded. Let no ceremony be neglected.

(Music and chimes until the audience has gone.)

Copyright © 1973. All rights reserved.

Reviews

from The New York Times, 16 February 1974:

by Mel Gussow

A father’s desire to be emulated by his son, a son’s desire for individuality are the timeless themes of Michael Smith’s new play, “Prussian Suite.” The father in this instance is King of Prussia, the son is the Crown Prince, but the play is less a tale about monarchy than about love and the absence of love.

This is a small chamber work, and for the occasion the author-director (who is also chief drama critic for The Village Voice) has turned Theatre Genesis into a chamber for a concert. The low stage is lighted entirely by large candles as footlights and is backed by a long ribbon of tapestry. The staging avoids preciosity, a danger in such a potentially rarefied atmosphere.

In one corner sit three musicians (John Smead, who composed the score; Michele Hawley; and Mr. Smith himself), playing a variety of instruments. The orchestra offers a flow of song that corresponds so closely to the mood of the play that at times it seems as if the score is the foreground, the text the background.

The text, intentionally, is repetitive. There are four actors—Ondine as the King, Georgia Lee as his daughter, and Jimmy Centola and Charles Stanley, who alternate in the roles of the Prince and his best friend. The last two play scenes, then switch characters and replay the same scene.

The purpose, obviously, is to add to the play’s musical texture, to treat the actors as instruments (a string quartet) furnishing variations on a theme. That effort is only half-successful because the acting lacks definition—what we see is simply a scene done twice in somewhat different styles.

“Prussian Suite” has a soothing, gentle effect. From the first line, “I feel myself falling through darkness,” the play is like a child’s dream—impressionistic and lingering in one’s consciousness.

Well, a new year begins. The Hot Peaches dispersed, all hoping that we will learn a lot from working with other heads and hearts and bring back our education to help our own theatre grow larger than it presently is. Lenny went with Jackie Curtis and Donald Brooks. Wilhelmina is doing a W. H. Auden showcase play. Ian is pulling himself together. Robert Arr is dementing in Queens. Marie is resting and wrestling with roaches in the East Village. Luke is having a nervous breakdown in Brooklyn. Sister Tui is in jail, and Marsha in Bellevue, and I am rehearsing a M. Smith play with Ondine, Charles Stanley, and Kate (?) at Theatre Genesis.

At the end of “The Magic Hype,” Michael Smith phoned me and asked me to be in his new play. After a few really hot conversations with Mike, things looked great. At his holiday party, as I sat sipping cider and munching homemade cookies, listening to the harpsichord and flute [sic], I suddenly felt foreign, a visitor to another land. Then, a week or so later, when I read the script, I was convinced that I was a foreigner because reading it was like reading another language. I do not understand it.

Rehearsals… well, everyone’s acting and I don’t know how to act, nor do I want to know how to act. I tried playing on several occasions, messing around with an accent, a stutter, etc., but that was promptly, if politely, halted. Are they going to make me act? Why? They seem to be trying real hard to be real. Do they want me to be real? On stage? Why would anyone want to sit for an hour or so and watch me be me…at a price? (Actually, admission at Theatre Genesis was free.) They can come and see me anytime, anywhere, for nothing! I don’t want to be real on stage, I want to be a fantasy. Oh well, I’m paranoid as hell and lost in a maze of off-off-Broadway tradition which surrounds not only Theatre Genesis but the actors, the director, and indeed, the very play itself. All I can do, I suppose, is try to be myself!

SUNDAY

Clocks changing completely fuck me up. Because of the fuel shortage the day has been shoved back an hour so that days are longer. I fixed my clock last night, only I fixed it the wrong way, so I woke up late, was late for rehearsal, and it seemed as if the day was threatening chaos.

However, rehearsal went quite well. We experimented, changing roles, doing them at the same time, etc. I was simple, as straightforward as possible, and, much to my surprise, it did not bore me as I feared it would. It did not turn me on, but it did not bore me, and that was an unexpected surprise. But all that role-switching! It’ll take me ages. And I still don’t really like not being able to play on the stage. For me, the stage is the playground of adults, as useful and important and enjoyable as a sandbox is for and to children. No, this seriousness is not for me.

SATURDAY

This play is putting me through changes. After a terrible day with Kay, who was having an awful time being real and trying to figure out how her soul would say the word “be,” she quit. If the truth be known, I think she felt that I was not going to work out. I guest my amateurishness (wow) really freaked her. Too bad, cause she was an awfully interesting person and a good person for the part, maybe a bit too strong, but I’ll bet she would have overcome that quite easily. I wonder if I should quit and maybe she’ll come back! I’ll have to think about that one.

After a day or so, there was yesterday… Yesterday, I prepared to play Cat, spent the entire morning rehearsing the part at home, before a mirror, on stage, off stage, aloud, etc. When I got to the theatre, I was told to play the prince. I should have said something, but didn’t. Instead I spent the whole day trying to be the prince, but he wasn’t anywhere around, and I felt, sounded, and looked awful.

Today didn’t go so well either. When the play gets freaked out, I enjoy it immensely. But on a straight level, it just makes no sense to me, I can’t see why people will like it or get into it. Yet Charles Stanley and Ondine are great to work with. I enjoy them almost as much as I do Mike. I just have to get into this head that they live in. Ondine said he goes out there to make the audience stand up and listen, to make them want him and love him, he needs them… He didn’t say anything about enjoying himself. Maybe after you’ve done dozens of plays that you enjoy Ondine had done very few plays; apart from John Vaccaro, I may have been the only playwright or director who appreciated him and would cast him in a seriously challenging role. you no longer are satisfied with just enjoying them and want something else out of it all… I don’t know. But I’ve got to try and find out, soon.

THURSDAY, JAN. 24

WHAT THE HELL IS GOING ON!!! While I was deflated at the prospect of no scenery and disappointed that there would be no lighting (bar candlelight), I somehow managed to get over it. Good. A silver star. Now they hit me with ‘no costumes’ and with a final blow… no makeup. There it goes, drifting away like so much smoke in the wind… all my fun, all my theatrical enjoyment, or at least a good part of it, lie in those four things. My sand castles, my sun, my getting dressed up in my parents’ clothes, my halloween mask… all gone. Faced with going onstage and presenting only myself, old, dull, boring me, is a prospect I disapprove of immensely. I’ll do it, but I won’t like it.

Ondine is a camp. Onstage he’s spit and fire, offstage warm, friendly, and very real, always hugging and joking and laughing, particularly at himself. “Do you believe that my only friend is Rotten Rita!” But he also takes himself seriously… “I will not do that play nude. No. Get yourself another king.” I like him very much.

Charles Stanley confuses me a bit. He’s a worker. From 8 a.m. till one or two in the morning he’s on the go. Starting with exercises he then goes on to dance and rehearse another play he’s doing, then on to our rehearsals, where he acts and builds and paints, etc., then out for a drink or ten at Phebe’s. He seems to be in such a rush that he hasn’t time to think of where he’s going. He’s getting terribly tired, and often it shows onstage. No doubt he’ll pull it together beautifully, but wow, he’ll probably kill himself doing it.

Michael Smith… well, he’s a fun person. I’m awfully taken with him. Want to get close to him, talk to his mind, his body, his soul. I’d like to spend a week alone with him and tell him who I am and who he is and find out who he thinks he is and let him tell me who I am and come away with part of him in place of part of myself which I’d give. There’s something wonderful about this man.

But he’s a boy, really, at 38. As a director he’s pretty good because he works hard and lets things happen without losing perspective of the possibilities of where the play might go. But he’s also somewhat weak in the face of aggressive strength. (He’d be dynamite in oriental theatre.) For example, he lets Charles push him around, e.g.,

M: Let’s do another runthrough. One isn’t enough.

C: Let’s not. It will die. (Actually it won’t. Charles might because he’s so damn tired from the La Mama rehearsal, but we need another runthrough.)

M: O.K. Let’s skip it tonight.

Michele, Mike’s girl, is a model of patience. She sits for hours, endlessly playing four strings on the tamboura, without variation, and she really gets into it. She’s a sweet person and seems as lost in the theatrical social swirl of off-off-b’way as I am in this play. She seems to want to be in the play and I don’t know why she isn’t. Anyone who wants to play should be allowed to play. I mean what are friends for if they won’t let you play with them?

The character of Wilhelmina has gone through changes and a half. After Kay, the method actress, we employed Eve, the motive actress. After spending four days and many hours on fewer pages of the script, Eve the sack. Actually, what happened was curious to watch.

One evening, Eve decided to go off to see a performance somewhere rather than coming to rehearsal. Feeling a bit rejected and defensive, the cast began talking about her. The talk turned into camp dish and that into a read. Before you knew it, Charles was putting her down, Ondine was reading her to the dirt, and Mike was agreeing. I made a feeble attempt to get back to the rehearsal, but there was no way that they were going to let this tiger escape now that they had it by the tail. They got into it, heavy. The snowball tumbled and grew. The conversation ended with the three of them considering other possible Wilhelminas. Next day, when I arrived, I was told that Eve had been given the sack. (Now where does that expression come from?)

The new woman, Georgia, is nice. She looks and sounds like Glenda Jackson. Now if only she could pull off a G.J. number… wow. But she’s not an actress, she says, she’s a person. Alright! She already seems to have the seeds of the character, I hope it flowers.

The play itself works quite well. It is abstract enough to do many interpretations of and with. Ondine spouts off continually about how great it is. In fact, he praises it so much that I find it hard to believe. I have a feeling that he doesn’t like it at all because he always seems to be trying to convince himself of its validity. Well, I don’t think it’s great, but it’s nice and loose and… well, who am I to say? We’re doing many things with it that seem to have so much promise.

Am reading the life of Bea Lillie and she sounds so bitter. I wonder if all comedians are bitter. Like Betty Hutton and the cliche says… Is Lucille Ball?

FEB. 1

Nothing seems to be going right and I’m terribly concerned with the play. Someone said that Ondine gets out there and camps it up and that in comparison the rest of us look like a bunch of wooden boards.

I think that Mike should have considered the audience a bit more. First off, while the candlelight is wonderful, after five minutes it must surely be an eye strain. With no costumes and practically no set, there is nothing for the audience to feast their eyes on anyway. The play itself is sweet and charming, but it is so heavily suppressed that nothing really happens, love affairs are hinted at but not allowed to happen, relationships are inferred but not revealed, characters are tied in knots, bursting with energy but not being allowed to live, events are implied but not permitted to occur. I guess this is very tied up with Mike as a person and his personal life, etc., who knows, but it must be, because a play, when you come right down to the nitty gritty, is but a mirror image of its writer and director, and he is both.

Other problems: A great number of scenes are repeated, verbatim, and while this works once or twice, it gets tiresome after a while because it serves no purpose and has no integrated meaning in the context of this play. Then there is Georgia who isn’t too interesting and me who can’t act. Ondine is quite good and people tell me that Charles is a really fine actor. Well, perhaps that is good for watching, but its value escapes me, because when we’re on stage together, I feel like he’s off somewhere rehearsing another play.

Why Mike asked me to be in this show I’m afraid I will never know. When he saw me I was this freaked out street person wearing a white wedding gown, backwards, my face a mass of colors, I had freaked out frosted hair, a chandelier on my head, and a Japanese dancing fan in my hand. After reading the play, I thought it would be nice to work with him. I felt a deep affinity with him. Something very basic in me went click, yes, o.k., definitely. I liked the others in the company. And, in time, I got over the no costumes, lights, etc. I figured, it’s his show and he is the director and we should do what he wants. Who am I to be any different from the rest? But I’m so out of place here.

Opening night and madness begins. As I sat putting on traces of makeup Charles freaks out… ‘If you can do it, we all can do it. I mean I could look younger by erasing the bags and hiding the wrinkles too.’ I don’t know where that came from, but there it was. Younger? Wrinkles? Erasing? Well, it was too weird, so, despite the fact that Georgia had on traces and Ondine was spraying his hair white, I rubbed it off, leaving, of course, much of it on. Next night, I walked in and Georgia has more colors and is not outdone by Ondine who is darkening his eyebrows. So, before going out, I sprinkle a bit of glitter here and there. Then, last night, I glittered down. Charles was outraged, but well, he’s a good actor. What have I to offer but my glitter!

But I’m so tired with it all not happening. The rehearsals that don’t happen because of the endless waiting for Charles, whom Mike is afraid of. The play that doesn’t happen. And the me that doesn’t happen because I don’t know what the hell is going down. But I must find out what this is all about. I must. Despite the audiences that don’t happen and the fun that doesn’t happen and all the other things that don’t happen. I must find out why all this non-happening is happening and what the hell it means. In fact, I am so taken up by it all, that I swear, the next play I write will be about this one.

FEB. 11, 1974

Well, another week of “Prussian Suite” and what have we? Two more arguments, a frank discussion, an acting problem, a glimmer of what their reality is about, a schedule, ideas for a new show, Tallullah Bankhead.

First week over, I find my rebellious tendency more under control. I went out there with makeup, with glitter, with earrings, with long flowing hair, and I got all that over with. This week I wanted to be me… whoever that was, is… whoever that person is that Mike wanted on stage. So I tied up my hair, threw out my earring and glitter, and went out to face the audience.

The first performance, I split my characters so that my prince was this nervous wreck (the new me sans trappings?), and my Katte was a hustler-smoothie type. As it turned out, the prince was too jittery, too phony. But somehow I managed all the scenes.

Second performance, my prince calmed down some, but still too fast. The nerves were on the outside too much. Mike said that I’m too external, meaning, I presume, that I’m basing my performance on the physical only.

Third performance I calmed the prince down and took my time. I think he worked. I tensed up for him, but minimized the jerky movements and cut the snips and snaps. Ondine milked the last scene for camp, so I camped with him and it seemed to work so that when he left the stage, I was able to pull the audience back together again for the final scene, something I’ve not been able to do up until this point.

The fourth night was a joy. I calmed my prince right down to a tensed, pent up, confused and suppressed person and played him against a cool, relaxed Katte. All went well except for Mike and his word mania. We argued.

Our first argument was Saturday night. Ondine camped the death scene and, fearing lest I lose the audience completely… a great and justified paranoia of mine… I picked up on his camp and camped. He fell, I picked him up… and dropped him. This went on three times and the audience had a ball. As he raved, I stalked the stage. It was funny, exciting, and we enjoyed it as much as the audience. So when he made his exit, I still had command and was able to bring the play back, sliding, on the weight of its own reality, to its own conclusion. Sitting in the dressing room after the performance, Mike comes in and, saying nichts to Ondine, addresses me:

M: Jimmy, you camped too much in that last scene.

J: It got very campy.

M: You can’t get campy.

J: But everyone else can?

M: No one else did.

J: Really? Look, Mike, I know what camp is. I work in camp most of the time. Ondine camped out there tonight. I picked up on it. How dare you come in here and single me out. Who the fuck do you think you are. Quite frankly, I am offended.

M: I didn’t mean to offend you.

J: Well, you have, and I don’t like it. If you can’t tell me how to handle that scene, please don’t tell me how not to handle it.

M: Well, you can’t camp it.

J: I refuse to go out there and make a fool of myself. The chair slips, Ondine jokes, the audience cracks up, and you expect me to deliver serious lines amid all that? I won’t do it. And until you tell me how to do it properly, I’ll do it the way I did it tonight.

Next day we met to discuss ‘things.’ Well, he didn’t say much and as per usual I did all the talking… fool that I am. I told him how intimidated he was by Charles and Ondine and that he was picking on me. He agreed. I explained that I’d gone through numerous changes to do this show only because I’d signed a mental contract to be directed by him. The company was completely hypocritical and I w/couldn’t be like that. He agreed, saying that the back-biting and lying, etc., was something they had lived with ever since the Caffe Cino days and he disliked it. Then he really blew my mind by saying that he didn’t mind arguing at all. Lola, after seeing this play, said that Mike was a mental masochist. I wonder if she’s right.

Sunday night he came backstage after the show all tortured and wrecked.

M: You must learn your lines. I’ve written a beautiful play and you say the wrong line. It’s as if I play the wrong notes.

J: Now Mike, why don’t you tell the others that? They get their lines wrong.

M: Let’s not talk of the others. It makes me crazy when you say the wrong lines.

J: Look, Mike, I’ve tried. I studied. I go over this fucking play every day, twice, and there are some blocks. Now, instead of sitting there and crying, suggest some way of learning them. Don’t come back here without reason. I don’t want to hear it.

M: I can’t learn your lines for you. You’re ruining the play.

J: Mike, please. Charles fumbles his lines so badly you can’t even figure out what he’s talking about. You’ve got some nerve. You really have. I can’t stand it. But I’ll read the damn book and try. O.K.?

Petty, petty, petty… but damn it, I will try.

An acting problem: There seems to be a way to take Ondine’s power (which is basically camp) and transfer it to myself but on a serious level. So when he exits I can hold my own. I don’t know how to do it. I can take his camp and camp it, then transfer my own camp to power of a serious nature, but short of that I’m lost. If I learn to make that shift from his camp to my seriousness, then the whole play will be worth it.

Harry said that I should just stare at him. Stare at him when he falls, glance up at the audience to incorporate them, then, in a moment of silence, stare back at him to give a pause before I utter a word. I must try it.

Their reality, it seems that they’re trying to be as natural and real as possible. Why I don’t know. M ike thinks the power of atmosphere plus script plus lights plus our natural selves is enough to entertain an audience. I think it is sufficient to appease and relax but I don’t have to go to the theatre to relax. I go for entertainment. But it’s his play, so I must give him ‘real’-ness, in its most uninteresting sense, if you ask me. The hustler Katte I have functioning quite well, I hope. The uptight nervous prince is still hammy. I must get him right. So, this is what long rehearsals are all about.

My new play is about children, the child in the man which takes over to varying degrees to the point where he can murder. In basing this idea on the making and breaking of “Prussian Suite,” I see Mike as killing me. i.e., the me who went on stage all glittered up and ready to fall in love. He kills that me in order to create another me, a me he saw in the glitter number, something he related to. Originally he was going to write me a drag role. After he met me he wrote, instead, the part of Katte… a hustler lieutenant who dies for the prince (himself?). But he has me playing bother roles… why! I know it’s not what he wants. Through the course of rehearsals he’s tried consistently to do away with the glittered me… to kill it and find the real me.

The play will also be about the individual Peaches. Exposing each of their childhood experiences, Tui and the nuns, Robert and the dwarfs, Marie and the Fascists, etc…. and showing how those experiences come to the surface in adult life. What they do when they surface, how threatening they are, how they kill much of the adult in order to have their say. The sanest of all must be the killer because he is hiding the most, acting most naturally, and of course the killer must be the director.

Reading about T. Bankhead is helping me to understand “Prussian Suite.” She camped her way through plays, but the play in which she was forbidden to camp, and given much confidence, is the play she did best in. Did her director kill the camp her for something else he saw there, that he identified with, did he remake her into himself… what happened?

FEB. 28

The play is over. I’d better write about it now while trace of its very subjective reality remain intact.

The third week was a seesaw rocking between Limbo and Hell. Ian and the Hot Peaches came to see it. They arrived en masse and made themselves incredibly comfortable, sprawling out on the floor as if they were guests of the prince. They really got into the atmosphere. Cynthia said I was artificial, Ian said boring, Marie was confused, Willie thought I was just plain dull. Cynthia said she was so bored that she had to resort to putting on perfume to keep from falling asleep!

Mike called a rehearsal on Saturday night, but Charles and Ondine never showed. I felt like crying, he looks so lost. Like a little helpless boy not knowing what to do. I know the feeling well. It is awful. Of course it didn’t help any when the two showed up roaring drunk and Mike said nothing, simply refused to deal with it. Intimidation, energy drained, helpless hopelessness, disgust, etc., prevent him, I suppose. Charles was so drunk that he slurred and mumbled all over the stage. It didn’t say much for what he thought about the production.

Due to disconnecting my alarm clock mistakenly, I arrived at the theatre on Sunday night at 8:45. They were concerned and said that poor Charles was wild figuring out how to play both parts. When I suggested that at our pre-opening runthrough, where Charles did not even show (I suggested I play both parts, just so that we could all have a decent runthrough), Mike said I wasn’t being ‘serious enough.’ Foreign languages always get to me.

Tommy and Mark were at the show. Tom said he liked it because it was different from what Off-Off-Broadway usually offers. It was a change from the mad camp, fire, madness, and color. Mark said nothing.

The Times reviewed us. It mentioned the play with obscured emotions, but definitely was negative about the players. Ondine freaked. “I don’t want to be in someone’s chronology of plays. That’s not why I came out of Pittsburgh.” He ranted and raved and Mike stayed clear of the dressing room that night… thank god.

Because I was tripping I missed a pre-show runthrough, but made the show, figuring that after everyone else had missed so many rehearsals and runthroughs, my missing one wouldn’t matter. But when I arrived, I couldn’t relate to anyone or anything there. It felt like a joyless function, a job with all in attendance there as routine, unexcited, unexciting, none of it made any sense. A bunch of children who had other things to do had been sent to the playground to play a game they weren’t into so they were making the best of it. Maybe it would rain. I got out of there as soon as possible.

The last Saturday show was so-so except for the final scene. The wheelchair fell off the stage and I got it. In my confusion, as Ondine spoke, I lit a candle, thereby drawing the attention to myself, which was a damn dumb thing to do. Well, Ondine freaked. I’d pulled the focus away from him and how dare I not deal with him for a fucking candle, etc. He was livid. In the dressing room he freaked. I spoke calmly and easily and he calmed down. But, like my director, rather than dealing with him and the situation, I ignored it and resorted to apologies and subtleties.

Sunday, the last performance was decidedly cool. We all arrived. Ondine apologized for his freak-out, we went on. There was a little party after the show, and when I asked for Ondine’s address, he said he’d get in touch. Ondine had been living in Pittsburgh. The only number I had for him was his mother’s house in Queens. I wanted to be in touch right there and then, but there was no way.

I tried to figure it all out by the party. Ondine brought his friends, who took him away early. Michele brought food. Charles brought a radio which he played in the dressing room even though the party was in the theatre proper. I brought myself. George brought her husband Playwright Walter Hadler was on the board of Theatre Genesis, hence a producer of the play.. No one could talk, and the atmosphere was charged and stilted. Johnny Dodd brought beer!

Afterwards, at Phebe’s, I ran into Ondine and friends, all of them drunk, obnoxious, loud, and very unhappy. I wanted to stay with them but it was not possible.

I sat with Georgia and Walter and there was discussion of how Mike never really dealt with her. I had to agree with that, he didn’t. Perhaps because she came late, or because she was a woman, or whatever, but the fact remains. Georgia said she often felt left out, sort of a token of the hetero world.

Charles joined us and was very positive, which surprised me, as I’d felt he was basically negative during the rehearsals and run. He said that Mike helped bring things out in him, but, somehow, I felt that he was, let’s say, ‘acting’ and not being as honest as Georgia. But who knows, maybe he was being honest. He just tries so hard that something doesn’t ring true.

Me? I felt pretty much let down. I think Mike deserted me, not so much out of the desire to do so as much as out of a reaction which was a consequence of his fear of both Ondine and Charles. At some points he actually turned against me and alienated me. I thought I was giving what I could, and I grant you, that was not very much. Mike took, remolded, discarded, hedged and hawed and often left me mid-ocean to sink or swim… according to his rules. I feel disappointed.

Of course, there is the acting problem… picking up another’s energy. I think I learned how to do that, I’m sure I have. So that makes the whole thing worthwhile. And of course there is my new play, “The Demented Diva,” which grew out of this play. There is the whole experience of that off-off-Broadway circuit and Ondine, whom I can obviously have no relation with, but whom I shall always remember warmly and fondly. There’s Michele and that old place in Brooklyn My apartment in Park Slope, where we held early rehearsals., so strange and empty, so stark, so undeveloped. There’s the kitten Katte, who became a young cat overnight, it seemed. There was the $60 [per week], which kept me alive, and soup with yoghurt in it. And there was, of course, far above and beyond all, Mike. Mike, whom I knew instinctively I’d not know again, just as I knew, months ahead, before I’d even spoken to him, before he reviewed us, long ago, that someday I would come into contact with this man who was called Michael Smith and who worked for The Voice and who had gray hair. I did know it. And it did happen. It happened!

SOME MONTHS LATER I wrote, but never mailed, the following response:

Jimmy—

So much came together in that play. Your letter/diary brings it back. I can’t make sense of it. Mostly of why it got so difficult for me, such a hassle with everybody, so exhausting. It was so hard to work. Ondine got drunk…but it’s not actually that, it’s…I don’t know what it is with him. I love him personally and as an actor…but…well he is dear to me and I can’t talk about him as some actor and be critical. The same with you. I saw how hard you worked, how far I pushed you out of your zone, how little I was able to help you directly—or even consciously. You were noble. I seem to have thrown everybody back on their own nobility.

I think the character of a play experience is made by the content of the play. For me anyway, when I am writer and director, I’m right in the middle of what the play is about, it’s in the middle of me, and the writing and production are sheer leaps into that darkness or light. In this case darkness. It’s a very grim and somber if beautiful play. Dry, cold, German/French. All the scenes happen at night except the last scene—Sunrise—and the sun could never rise unless the King actually died, and Ondine only did that once, in rehearsal in Brooklyn, and scared himself and never dared get it in control for fear it would happen again.

Think what the play is about, the story—

Too bad I wasn’t stronger for everybody, holding everybody up, instead of acting so confused and being diverted from my own vision—except I wasn’t diverted from my vision, that was it—just held back at times by everybody feeling so fucked up. And is that anything personal or technical or a true image of the people’s lives and world? Actors have to be prepared to act out the nightmares as well as the sweet dreams of their world—as you well know.— Well I don’t mean to get pompous, oops, but I’m sorry I didn’t manage to make it possible for people to get what they were doing under control.

There is something very elusive about you for me too, I am right with you, I recognize you, I feel the affinity of our essences, but where are you coming from? Someplace else, for sure. As if in some way we are blind to each other. I can’t see your thing with the Peaches. I saw you as an actor in a rather small part, and banging a gong at St. Clement’s, giving out a dazzling power of love. And of course that power is in you, not in the decor, makeup, or whatever you’re wearing, which is just something to suit the particular show you’re in. But how to get you to see that which is obvious (to me)? I’m sure you didn’t put yourself through so much self-doubt and so on to reach those other performances. You say in your diary on opening night that the play is sweet and charming though in fact it is about death and failed love and innocence sacrificed to desinty and history. Nowhere in all you say about me do you seem to noticed that I was playing music in “Prussian Suite,” which is a play nearly as much of music as of words and action (3 to 4), that I too was on that stage giving a performance. You seem in the diary to see me only in so far as I affect what you’re doing, as if I have no other reality. I’m not complaining—ignore any huffy tone any of these words may have: it’s the usual actor-director imbalance, where the director is supposed to be concerned with every actor but the actor is only concerned with himself. I wanted the actors to get it together so I could concentrate on what I had to do, which was play music.

Enough ranting and raving.

I could go on for hours about all this.

I wish you could have seen the play we did next, in Denver in June, “A Wedding Party,” a comedy, in which Michele played a lyrical grandmother who gets married to a drunken visionary. The stage was full of trees and everybody wore costumes and makeup. The musicians were up in the treetops going tweet tweet and humming.

“Prussian Suite” though was a grappling with my long-delayed coming of age and ten years of big-city karma and god knows what else, and what a long strange trip it is!

Thanks for the letter and diary.

In friendship too,

Mike

P.S. I have played the WBAI tape to my father and a few other people and to myself and I really love your performance. In fact I feel proud of the whole thing.