“Half Life”

Unproduced

I wrote this play in 1983 in exile, having got myself stuck for years in wage slavery under David Way, the harpsichord genius, living in Rhode Island with Michele, who had suddenly gone gay, and our two sons, Julian and Alfred, whom I loved with the greatest tenderness, loving being their father. I looked back for a subject to my lost theatrical life and the circle of people I had been closest to. The central characters, Art and Saïd, were superficially inspired by my friends Joseph Chaikin and Jean-Claude van Itallie, who had collaborated on “The Serpent,” the great early success of the Open Theatre, but the play hardly even tries to be fair or truthful about them. In addition, parts of the plot were suggested by stories Jean-Claude had told me, and I worried that he would be insulted and angered by “Half Life”; as a result I have not put it out much, though I believe in its charm and immaculate construction and would love it see it brought to life. The title refers to Plato and is certainly not meant to reflect on anyone’s life choices; it is a heartfelt play and has more to do, surely, with my own situation at the time I wrote the play, relishing my sweet family but painfully cut off from my artistic work and community.

“Half Life”

Cast of characters (in order of appearance):

SAID RAJ — a playwright in his thirties

ART MAGINNES — an actor

IRENA — a painter in her twenties

EDMUND SIMPSON — a drama critic

CARLOTTA MENDEZ — an actress

PLAYGOERS

Scene 1

The outer lobby of a Broadway theatre. We are facing into it directly, as if through an unseen bank of glass doors fronting on the sidewalk.

Upstage center is a pair of closed double doors leading to the inner lobby. Downstage right is the box office, seen from such an angle that the person inside is not visible. At the other side is an inconspicuous door leading to the manager’s office.

Displays in glass-fronted cases advertise a play called “Scales” with posters, blown-up photos, and glossies of the actors. IRENA is looking at the pictures, taking her time in getting to the box office.

SAID enters through the center doors, wildly agitated. He is practically tearing his hair. He breathes deeply, shakes himself, stretches. Looking around desperately, he starts to go back in, chnges his mind, and begins striding hither and thirther in a frantic and disjointed way, saying fragments of lines to himself.

SAID: … Your father… The man you call Father… He who fathered you upon your… My God!… This poor old man… Look upon your son… Blech!

IRENA: Excuse me, aren’t you Said Raj?

SAID: Yes I am.

IRENA: I just want to tell you how deeply I admire your work.

SAID: Well thank you. Thank you for saying so.

IRENA: People must tell you that all the time.

SAID: No, no one appreciates me… What do you like about it in particular?

IRENA: At the university the faculty is unanimously converted to your acting method.

SAID: That’s Art Maginnes’ method, actually.

IRENA: Well, you work together.

SAID: So what does that mean?

IRENA: Sorry, am I disturbing you?

SAID: No, no, of course not. (Pause)

IRENA: What is happening here today, if you don’t mind my asking?

SAID: An ordinary rehearsal. (Pause)

IRENA: I came to pick up tickets.

SAID: Really? How wonderful!

IRENA: Now you are sarcastic.

SAID: I am not, I am not, really. I am thrilled that anyone wants to buy a ticket for my play, actually pay money to see it. You have no idea how important that is to me. (ART MAGINNES enters through the center doors.) Excuse me. (He goes to ART.) Can’t we just stop for a few days and wait for the air to clear? I am simply not ready for the critics. I need a little time to think.

ART: Well, what do you want him to say?

SAID: Oh, go on and say “Your father.” I don’t care.

ART: That’s good. (Pause) What’s the matter, now?

SAID: You are changing too much! You are changing everything!

ART: Only when you agree.

SAID: I can’t say no every time you ask for a change, but you want to change everything.

ART: Of course. This is how we collaborate. You are not the only one who has ideas, you know. We are not puppets. We are not machines. You are not Shakespeare.

SAID: You would change Shakespeare.

ART: Of course I change Shakespeare! And stop arguing with me in front of the actors. You may be confused, but don’t confuse the actors.

SAID: I am not confused. I am furious!

ART: You don’t like what I am doing?

SAID: I love what you are doing. Believe me.

ART: The play is getting very good. We are not damaging your play, we are purifying it. We have to burn the impurities out of ourselves, it’s the only way. We are all as hot as you are. Come back in. We need you. (They go into the theatre.)

IRENA (At the box office): I have seen every one of his plays beginning with “Patrimony” at the Second Level. It was the first time I came to the Village. A girl in my life class brought me. Afterwards we went to a dark bar that was full of women. She wanted to seduce me, but I was impossibly naive, or at least I pretended to be. I saw “Breakthrough” in Paris on their tour. I just happened to be there at the same time. I saw “The Re-Creation of the World” in Los Angeles. So I have to come. It really means something to me. I suppose everybody feels that way.

(The lights change. The center doors burst open, and a crowd of chattering PLAYGOERS spill into the lobby. IRENA is lost among them.)

FIRST PLAYGOER: We’re not going to make it to the train.

SECOND PLAYGOER: We can stay with the Condons.

FIRST PLAYGOER: I don’t want to sleep with Louise.

SECOND PLAYGOER: You don’t have to sleep with Louise.

FIRST PLAYGOER: That’s what you say.

SECOND PLAYGOER: I don’t have to sleep with Harry every time we see them. Anyway we probably will make the train. The second act probably isn’t very long.

FIRST PLAYGOER: Remember how short it was in the last one?

SECOND PLAYGOER: Shorter than the intermission, I think.

FIRST PLAYGOER: It seemed hardly worth having sat down, or gotten up.

SECOND PLAYGOER: It’s wonderful how we agree…

THIRD PLAYGOER: … He is an incredible actor, I have to admit that.

FOURTH PLAYGOER: Did you see him in “The Fallen”?

THIRD PLAYGOER: I never saw any of them before tonight.

FOURTH PLAYGOER: What have you seen? You haven’t seen anything.

THIRD PLAYGOER: You make me feel like I’m not worth talking to.

FOURTH PLAYGOER: You are worth talking to, if you would just say something…

FIFTH PLAYGOER: … What do you think?

SIXTH PLAYGOER: I’m speechless.

FIFTH PLAYGOER: Really!

SIXTH PLAYGOER: He is less an actor, I think, than a hypnotist. He bewitches us with a secret music of the spirit. I see it pouring out of his heart center like a golden elixir. We all must love him in spite of our reservations about what he is saying.

FIFTH PLAYGOER: It’s too intellectual for me.

SIXTH PLAYGOER: Well, it has to be about something. Don’t be put off by the pretentious tone…

(IRENA appears, recostumed, on the arm of EDMUND.)

IRENA: Did you hear the sirens during the conquest of Mexico? I hate that. It always happens at the most sensitive moments. It makes me think war has broken out. Really, I still have the shivers. Put your arm around me. (He does.)

EDMUND: There, there, my love.

IRENA: I feel completely open, completely susceptible. This is my aesthetic sensation. It makes me afraid of art. These things are more real to me than my own life, like my dreams. The state of my body and my mind has no effect on how I will react to a movie or a play, but the book I am reading dominates my mood. I suppose everybody feels that way.

(SAID comes rushing through the crowd and bumps right into them.)

SAID: Oh dear. Excuse me.

IRENA: No no. Hello. I would like you to meet my fiancé, the critic Edmund Simpson. This is Said Raj, the author.

SAID (Shaking hands): Hello. Glad to meet you.

IRENA: We can’t wait for the second act. It’s so exciting. I think it’s the best thing you have ever done.

SAID: Thank you. Will you excuse me? (Goes off into manager’s office.)

IRENA: How could you give him a bad review?

EDMUND: I don’t trust him. He is too fascinating.

IRENA: It’s like smashing a marvelous insect. You think it’s a mosquito so you smack it, and there it is with its marvelously jointed legs akimbo, its little shiny fairy wings forever still, its wormy little body bent, the life gone out.

EDMUND: I won’t give him a bad review. I’ll quit first.

IRENA: Do you want to talk about it now?

EDMUND: I don’t want to think about it till I have the typewriter in front of me. Say anything you think of, though.

IRENA: I can’t tell the actor from the act. He makes us share his trance. We are in the grip of his compulsion, his will, the writer’s and the actor’s strangely joined. I’ve heard they are lovers.

EDMUND: Really? I didn’t know that.

(An electric bell rings. Everyone exits through the upstage doors, which close. The box office closes. The lights change. CARLOTTA, an actress, comes in through the center doors followed by ART, who has that special look of an actor who has just taken off his makeup. She waits for him.)

CARLOTTA: Was I good?

ART: How should I know if you were good? You remembered your lines. You gave me my cues.

CARLOTTA: What’s the matter?

ART: Was I good, was I good! How long have we been working together, three years? It is completely wasted. You have completely missed the point. (Pause) Was I good?

CARLOTTA: You were sensational. You always are. The play would be nothing without you.

ART: No no no no no, I would be nothing without the play!

CARLOTTA: I hate the play.

ART: Carlotta, the play is the only thing there is. I don’t mean the script, the script is whatever it is, I mean the play we do, the play we make out of the script and ourselves and whatever grace the moment gives us.

CARLOTTA: Everybody hates it.

ART: You are mistaken, Carlotta. Everybody loves it.

CARLOTTA: Well I don’t care. What are you going to do now?

ART: We’re all going to the Cedar. Don’t you want to come?

CARLOTTA: Will you come over afterwards? I’d like you to come over.

ART: I can’t tonight. How about tomorrow?

CARLOTTA: All right.

ART: In the morning?

CARLOTTA: Come for breakfast.

ART: I’ll come after breakfast.

CARLOTTA: Good. (She kisses him and leaves. SAID comes in.)

SAID: I don’t want to own you.

ART (Laughs): No chance of that. It went well, I think.

SAID: Marvelously. I’m grateful.

ART: Are you ready? I told the others we would meet them at the Cedar.

SAID: Why the Cedar?

ART: Why not? It’s pleasant. I didn’t care. Come on.

SAID: Wait. I want to talk first.

ART: No, we can talk later.

Scene 2

SAID’s small but luxurious bedroom. SAID and ART are in bed in each other’s arms. Morning.

SAID: Do you want some breakfast?

ART: In a little while. Let’s have the moment while we have it.

SAID: Do you hear explosions in the distance?

ART: Go ahead and be happy. How do you like being famous?

SAID: I’m not very famous.

ART: Well, no. How do you like being rich?

SAID: I’m not rich.

ART: You might as well be. I wish you would rub my back.

SAID: I will. Roll over… Get rid of the pillow… Now relax. (Rubs.) How do you feel? You feel soft and relaxed and smooth.

ART: Well I feel satisfied. You are a very satisfying lover.

SAID: Shhh. So are you. (Rubs.)

ART: And I am partly satisfied with our play. We have completed the first step honorably enough.

SAID: What do you mean first step?

ART: I want to go on with rehearsals. Otherwise we will harden in our parts. It would kill me to do it over and over always the same.

SAID: I don’t think they will do it.

ART: Do what? Who?

SAID: How does that feel?

ART: It feels divine. You can go all the way down.

SAID: I don’t think the actors will do it. I know I will not do it. The rehearsals are the best part while they are happening, but then you go on to something else, another phase. We got it right. It’s working. You got it right. You should be getting famous, not me.

ART: You really will not come?

SAID: I don’t want the play changed any more. (Stops rubbing.) Is that enough? (ART is still.) Are you ready for some breakfast? (No response.) Shit. What have I done? (Gets up, naked.) Come on. Speak to me.

ART (Stretching and rolling over): I was almost asleep. I don’t know why I am so exhausted… Yes, breakfast.

SAID: We should start right in on another project while we’re hot.

ART: Where will we get the actors? I don’t want to work alone. Do you have an idea?

SAID: I’ve written something.

ART: Where am I going to get the time? We’re stuck in your hit.

SAID: I’d like you to read it.

ART: You know I can’t read scripts. You should read it to me.

SAID: All right, I’ll read it to you.

ART: I can’t do it today. I have to get out of here right after breakfast. How about tomorrow? No, the next day…

SAID: It doesn’t seem very spontaneous. Can’t you just read it?

ART: Actually I have an idea for something I want to work on for a while on my own. Maybe you should work with someone else.

SAID: I don’t want to work with someone else. It is meaningless without you. I don’t know how to do it without you.

ART: You should learn. Really. I am not trying to be cruel.

SAID: I know you’re not.

ART: You won’t let me do what I want to do, and I won’t do what you want me to do. You should find someone who will do what you want, or learn how to do it for yourself.

SAID: Is this something you have been thinking about?

ART (Up and dressing): No, it’s spontaneous. You wanted spontaneity.

SAID: Well, maybe I will. I didn’t want to hurt your feelings.

ART: You’re not going to hurt my feelings. I have more interesting things to think about, actually.

SAID: Like what?

ART: There is a real world, you know. It isn’t all art and self-improvement. Sometimes I hate your precious feelings and your precious art. I hate you and everything you stand for.

SAID (Slipping into a kimono): Come on, you know me better than that. Don’t blame me for my father’s politics.

ART: It isn’t politics I’m talking about, it’s money. It’s an attitude. Money is politics. You can’t help who you are. You know how much I admire you. I mean personally.

SAID: I love you.

ART: I know you do and it’s a lovely gift. That isn’t what I’m talking about. (Embraces and kisses him.) You feel wonderful. I love the way you feel. You feel so strong. Your muscles are so distinct.

SAID: Let’s go back to bed.

(They fall down on the bed and roll around together for a minute, kissing and hugging. Then ART sits up.)

ART: Come on, lover. Breakfast time. Bring on the papaya. (SAID gets up, with lingering touching.) So what is it you have been writing? What is the subject?

SAID: There isn’t any subject. It’s about people, for a change.

ART: What do they talk about? What do they do? Do they do something?

SAID: They don’t do anything. What are they supposed to do?

ART: That is the question exactly. What are we supposed to do? When you start answering that question, you will really have something. (SAID goes out. ART makes a telephone call. Into the phone:) Jim, this is Art… Yes, it was fine. What about today?… What time?… I don’t care if I do go to jail… Good, I’ll be there. (Hangs up. SAID returns with papaya halves on plates.) I’m going to a demonstration against the neutron bomb this afternoon and I may be arrested. Don’t try to tell me I shouldn’t go. If I don’t show up for the performance, Ben Bogert will do my part. We’ve rehearsed.

SAID: When did you rehearse?

ART: The other day.

SAID: I won’t be here. I’m going to Los Angeles with my father. Don’t you remember?

ART: The papaya is perfect. You always know exactly what to eat. Something you learned from your father, no doubt.

SAID: Do you want me to come with you?

ART: You can make up your own mind about what’s important.

SAID: Why do you say things like that? You don’t have to lecture me on morality. You are not my spiritual teacher. I am not one of your fans.

ART: Take it easy.

SAID: If you want me to come with you, I will come. If you don’t care, I won’t.

ART: Of course I want you to come. I always want you with me. I may not pay much attention to you, though.

SAID: I think I will go to California.

ART: Suit yourself.

SAID: Why are we arguing?

ART: I’m not arguing. I’m happy. Or at least I was, until you started picking a fight.

SAID: I will be back on Tuesday. Do you need me before that to bail you out or anythng?

ART: Why are you going to Los Angeles?

SAID: My father wants to buy a house on the beach. He wants me to look at it.

ART: Will you see anyone?

SAID: Late, after he goes to bed, I will probably call someone over. Why? Do you mind?

ART: How could I mind?

SAID: Well you might. These things are not always logical or justified.

ART: I don’t mind what you do.

SAID: I don’t believe you.

ART: You’d better believe me. You should always believe what people say. It’s the only thing you have to go on.

SAID: Don’t lecture to me! God!

ART: I am a teacher. How can I not teach you? You are so frustrating you make me mad. (Laughs.)

SAID: I have an appointment at Twentieth Century Fox. Tell me not to be nervous.

ART: It’s all right to be nervous, but try to relax your asshole.

SAID: I don’t even want them to buy my play. They’ll ruin it.

ART: They’ll never do it. Take the money and run. How much are they trying to give you?

SAID: I don’t want to sell it.

ART: Why are you lying to me? Of course you want them to buy your play. It’s the main thing you do want, isn’t it?

SAID: In a way.

ART: And you are planning to keep all the money yourself?

SAID: Of course.

ART: And take all the credit?

SAID: I did write it. I am the one who sat down at the typewriter and wrote it. It is the script they are buying, not the performance.

ART: This is not exactly honest, my dear.

SAID: Don’t lecture to me!

ART: But I must remind you of what is true. This is disingenuous.

SAID: I am not pretending anything. I am stating my position. If you want to argue about it, argue with my agent or my lawyer.

ART: I didn’t know you had a lawyer.

SAID: Well, I do.

ART: Since when?

SAID: Since I started this production. I knew this play would be a hit. That was the whole idea. Don’t be dim.

ART: Well, what else is new?

SAID: I am probably buying the house in the Pines. I hope you will plan to come out with me for the summer.

ART: I’d love to. Not the whole summer.

SAID: I mean it about Fox. I thinking I can get a better deal where I can keep control of it myself. I don’t want to direct it, but I do want a hand in producing it.

ART: Where am I in this?

SAID: Well, I hope you are starring in it, but they may insist on somebody with a bigger name. How do you feel about that?

ART: I’m not going to tell you how I feel. What difference does it make how I feel? How I feel is my own material, I think.

SAID: So for that reason I hope he buys the house in Malibu. He will hardly ever be there. In any case I don’t intend to miss the retreat in Mexico, which is the whole month of October. You probably have plans of your own.

ART: I can make some. I want to go to the beach sometime in the course of the winter. Maybe Haiti.

SAID: Shall we plan on it? The beginning of March?

ART: Yes, let’s do. What else do you have to eat?

SAID: Coffee is made. (Goes out. ART consults his appointment book, makes a note or two, telephones.)

ART: This is Art Maginnes. What do you have for me? (Makes notes in his book.) All right… All right… Where is she?… When was that?… All right, I’ll call her. Would you tell any of the actors who call that there will be an extra rehearsal at the theatre at five, and supper will be provided… Anything else?… No, I’ll try to call you again after lunch. If I don’t, call Fred Birnbaum and tell him I’m in jail. (Hangs up. SAID returns with a tray of coffee, bagels and cream cheese, etc.) Don’t you wish somebody would come over?

SAID: Who?

ART: Anybody you like. I’m not particular. (They settle down to breakfast.) I wish we had a newspaper.

SAID: Shall I turn on the tv? Oh, it is on.

ART: I’m interested in those people in South America who live to be 130, 140. They’re in their 120s and they are still working in the fields, and fucking, for all I know. Let’s do something about people who are very old, 150, say, or 200. Think how much they must remember… Think how different their perspective must be… Does that interest you at all?

SAID: How do they feel about dying?

ART: The longer you live, the less you care.

SAID: You don’t feel that way yet, do you?

ART (Laughs): I don’t know. I’m young. I don’t know how they feel about anything. That’s not the point. I want to make them up. I don’t care if they actually exist. What do I care? It’s all I can do to care about people I actually know. You, for example. You’re so difficult. You’re always jumping out of reach. I still care about you. That’s not the point.

SAID: That’s not what point? What is not the point?

ART: We won’t always be young. We can imagine something else truly even if it is not literally true.

SAID: I don’t know if I agree with you.

ART: Of course you agree with me. You don’t have to have your own point of view about every little thing. Anyway for the sake of argument we can make these old people up without actually having to know them, or feeling responsible to them. Of course it is our own point of view.

SAID: What are you getting at?

ART: Forget it. Eat your bagel.

SAID: Do you like them?

ART: Of course. I love bagels.

SAID: I don’t like you missing a performance.

ART: Well, I probably won’t. You know I very seldom miss a performance. I never can sleep when I miss a performance, no matter where I am. It’s the utter pits. Very little is worth it. But you know sometimes I just have to get out of this little world of perfect values and say yes I know, yes I know, and tear out my heart and share it with every victim of the stupidity of the world and the delusion of reality. Then I come back and give you a real performance. If I don’t I can’t sleep. Only after the performance.

SAID: Will you be all right?

ART: I have to go. I promised Carlotta. Really that’s not the right thing to say, you see? I don’t know. I think I make too many judgments.

SAID: Well, I’ll see you on Tuesday.

ART: Call me tonight, will you? You can call late. Whenever you’re alone.

SAID: I wish you were coming with me.

ART: You don’t really. Have a good time. You deserve a little vacation. This has been very hard work—fun, but still work. Why else do it? (Puts his arms around him. They kiss.) Have a safe trip. Hurry back.

SAID: You take care of yourself.

ART: I do, I do. Bye. (Hurries out.)

SAID: Bye.

(He flops down on the bed and stares at the tv. After an extended pause the door buzzer buzzes. SAID slowly gets up and reties his kimono. EDMUND appears in the doorway.)

EDMUND: Hello. There you are.

SAID: Edmund! What a surprise to see you here!

EDMUND: I hope I’m not intruding. I saw Art Maginnes on the way out and he let me in.

SAID: Not at all. Welcome to my everything room—bed chamber, studio, breakfast room, pool room, whatever you like. Would you care for some coffee?

EDMUND: Yes, that would be very nice.

SAID: I’ll get another cup.

EDMUND: It’s about my fiancée, Irena.

SAID: Excuse me. (Goes out.)

EDMUND: I believe you know her. She has a fixation on you. I don’t know how to explain it. Never before has she acted this way, or so she tells me. I believe it is a kind of madness. I love her. I want her to be happy. So I thought I would come over and talk to you. Maybe we could get to be friends, you know, have dinner together a lot, that kind of thing.

SAID (Returning with fresh coffee): I’m sorry, I missed most of that.

EDMUND: My wife is in love with you.

SAID: You can’t be serious.

EDMUND: I know what you mean, but I’m afraid I am.

SAID: But I’m homosexual.

EDMUND: Yes, she told me that. In fact she said you are married to Maginnes, more or less.

SAID: Not really. Well, it’s very interesting to meet you. I’ve enjoyed your review.

EDMUND: I realize I’ve never properly been your champion.

SAID: Don’t you mean I’ve never properly been your champion? Well, I don’t expect it.

EDMUND: Well, you shouldn’t, but still it’s too bad.

SAID: What do you want?

EDMUND: Why don’t I interview you?

SAID: What? Now?

EDMUND: I’ll give you some publicity, as a favor to my wife. (Whips out a small recorder and switches it on.) How do you feel about the success of your play?

SAID: Art Maginnes should have half the credit for everything I have achieved. He is more than an actor. He is an inspiration.

EDMUND: I understand he actually wrote some of the lines.

SAID: Actually, though, I did write the play. I am really very happy that people like the play. I feel I have worked hard for this first small success, and paid my dues, in spite of my having some real advantages such as money, education, and so on.

EDMUND: You feel you are part of an elite class?

SAID: Well of course artists and intellectuals are an elite class. It is not possible to hide that. But the rich are not an elite. They are nothing. They are only rich.

EDMUND: Yet somehow you feel you are able to speak for the poor in spirit.

SAID: The actors have helped me very much with this. This is the privilege of artists, not to be confined inside the imagination of any class.

EDMUND: What is your advice to other young writers?

SAID: Keep grinding it out.

EDMUND: Thank you. (Switches off the recorder.) That will make very good copy. Quite inspiring.

SAID: Thank you. I try.

EDMUND: Will you have dinner with us Sunday night?

SAID: I can’t. I’ll be in Los Angeles.

EDMUND (Sitting on the bed): Don’t you love Los Angeles?

SAID: No, I hate it.

EDMUND: It is my idea of heaven. I have always wanted to live in Los Angeles. Beverly Hills, I mean, really, or Brentwood, in a house made of glass in a secret garden.

Scene 3

SAID’s larger, still more luxurious barn bedroom in the country, fifteen years later. SAID seems much more relaxed and happy. IRENA, extremely beautiful now, is in bed with him. Morning.

IRENA: He wants me to marry him again.

SAID: Are you going to?

IRENA: I don’t know.

SAID: What does he say?

IRENA: He says we are not happy apart. We have not found anything better. We only miss each other.

SAID: It’s true, too, isn’t it.

IRENA: No, it is not true. I love you. I love you better than I love him. Why don’t you believe me?

SAID: I do believe you. Wonderful.

IRENA: It is wonderful. I am free. I will marry you. Let yourself love me. I am easy to love. (Rising, nude.) Many people love me, you know, and I love only you. (Slipping into a kaftan.) And you love only Art, or art, or yourself, I don’t know what difference it makes. I don’t demand anything but time and effort.

SAID: You are marvelous, Irena. It is never any effort with you.

IRENA: Then why do you hesitate?

SAID: I don’t trust myself.

IRENA: You’re not having some kind of thing with Edmund, are you?

SAID: No, only that once.

IRENA: Are you sure?

SAID: Well, one other time. That’s not it. I like Edmund. I really do. I don’t want to hurt his feelings.

IRENA: You have to hurt people’s feelings sometimes. Some people don’t take getting their feelings hurt all that seriously.

SAID: Do you believe that’s true?

IRENA: I don’t know if it’s true or not, but it’s what I think. I know I cannot do what people think I should do, I have to do what I like. I am a free woman. You like me, don’t you?

SAID: You know how much I like you, Irena.

IRENA: You like to be with me, no?

SAID: I am happier with you than I have ever been before.

IRENA: I want to marry you.

SAID: Then you will not be so free.

IRENA: I will have you in my own bed, and my children will know where to find me. Do you want a child? I will give you children. I would love to give you children.

SAID: Oh Irena…

IRENA: Don’t give me that. What do you say?

SAID: You make me so sad. I am full of sadness. You show me all I might have had. It’s too late. I want my own bed. I want my freedom. I want to be gay, I don’t want to be straight. I love you too, Irena. I only wish you were a man.

IRENA: That’s the weirdest thing anybody ever said to me.

SAID: Surely not.

IRENA: I will be a man for you. I am a man. What is the difference? Sex is sex.

SAID: I wish I was a man. I’m just not ready. I have to see it from my own point of view. I’m just not ready. You want us imagining I am someone else? We’d be completely out on a limb.

IRENA: You’re already out on a limb. I will make you a man. Look at yourself. What do you have now?

SAID: Real estate, looks, brains, ambition, money. Two lovers. What on earth do you mean? Look, Irena, I don’t like people putting me down. If I want psychotherapy, I’ll pay for it. Are you doing breakfast or am I?

IRENA: It’s your house. You do it. (Pause) Are you coming in for the opening of Art’s play?

SAID: I thought I would.

IRENA: I hope you have a ticket.

SAID: I’m sure I do. Surely they are around.

IRENA: My dear, it is a complete sellout. It is the hottest hot ticket in town.

SAID: Really?

IRENA: He is a real star now, you know. This is not downtown, you know. He did it by invitation once last week, you know, and the word of mouth is fantastic. He has made it all his own now, you know. There is no author, no actor, no character—it is just one thing, he just takes you inside his mind.

SAID: Have you seen him do it?

IRENA: Edmund saw it. You must have seen what he wrote.

SAID: I must have. I’m sure I must have.

IRENA: He wrote it in the Times, you know, the usual pre-opening thing where the artists exhibits his personality.

SAID: I don’t see the Times up here.

IRENA: It wasn’t so much what Art said himself. He said he put it all into the play, and he wanted to talk about Ireland and the political prisoners in the Philllipines. You know how he is. It was Edmund’s tone that did it. “Exemplary” is the word he used, several times, without any apparent irony. And you know how ironic and skeptical Edmund is. I mean his persona.

SAID: It isn’t the sex. I haven’t had sex with Art in years.

IRENA: Anyway, he has a whole other life now.

SAID: No. I don’t want to talk about him. I could marry you. It wouldn’t make any difference with him. How can I explain? You don’t want to know the truth.

IRENA: I do, though. Why not?

SAID: It’s too dreary. You would feel insulted. I would lose you. Can’t we go on the way we are?

IRENA: We can’t. I don’t like to be alone. If I go back to Edmund, it is for good, with my whole heart. I will not be free to go abroad with you. I will not sleep with you. I will not divide myself in two. I will be friends with you of course! We will always be friends. (SAID gets up, puts on a robe, and leaves the room.) I love you. You are impossible, you know, but I have never known your like. Your power must be how strongly you consider yourself. You never have a doubt about the value of your will. You are far too smart. Anything anyone thinks about you is already worked out in your mind, and more precisely. You have learned to live alone very well. But you know you need me. (Pause) I suppose everybody feels that way. (Pause. Then she telephones, dialing eleven digits. Into the phone:) Good morning, darling. How are you?… Well that’s good… I’m here with Saïd. It is very beautiful, you know. The colors are fantastic. The air is full of prana. How are the boys?… I miss you all… Yes, I really do. Edmund, I do want to come back to you. I have thought about it well. I have decided. And I promise I will be happy… Yes… Yes, so do I. No, no regrets, no remorse… Yes, we are coming down this afternoon. I will be home tonight… I am too. Don’t cry, I love you… Yes… Yes… I’ll see you tonight… Thank you, darling… Goodbye. (Hangs up.) There. That takes care of the rest of my life.

(SAID returns with the breakfast tray.)

SAID: The mystery is gone from it completely, you know. There is no more mystery in cock. There is no more thrill in breaking the barrier of propriety. It is true I am afraid of you because you are a woman. But there is still something else, something positive, a fascination. Something about it stirs me, I am stirred, I am stirred. Maybe it is fascinating because it is always frustrating, always incomplete.

IRENA: Why don’t you just forget it? It sounds so boring. That would be an interesting experiment, no? You can change habits if you want to, you know. There is no coercion.

SAID: It’s a compulsion.

IRENA: Get over it! It’s all right to get over it. People do get over compulsions. You will still be you.

SAID: I don’t want to.

IRENA: It doesn’t sound very satisfying.

SAID: It is never satisfying. That’s the point. You are satisfying. I didn’t know what satisfaction was before I made love with you.

IRENA: I don’t care what else anybody does as long as they do right by me, you know, anyway. I suppose everybody feels that way. But never mind. I’m famished. What exotic delicacies did you bring us for breakfast today? (A knock at the door.)

SAID: I found Carlotta wandering around in the kitchen confused so I invited her to join us. Come in, Carlotta. (CARLOTTA comes in.) Papayas. Duck eggs. Carrot juice. Yoghurt. Tea. Sit in this little chair, Carlotta, and I will put the tray on this little table right between us.

CARLOTTA: I would rather sit on the floor.

SAID: I hope you slept.

CARLOTTA: I got up at five and ran five miles.

IRENA: Really?

CARLOTTA: I ran clear down to the blacktop and back. That’s five miles, and most of it uphill. When did you get here?

SAID: Carlotta is recently divorced.

IRENA: Yes, I was sorry to hear that. Divorce is such a drag.

CARLOTTA: It never was a real marriage.

SAID: You can’t say that, Carlotta. You can’t go back afterwards and say your will was not in it, when we all know it was. We’ve all broken our hearts. It was a real marriage, and what’s more it was a good marriage. That’s what you’re mad about.

IRENA: Where are you living? What are you going to do?

SAID: I told her she can stay here. You can stay here all winter if you can stand it. I don’t like the house to be empty so you would be doing me a real favor.

CARLOTTA: Is everybody coming up for Christmas?

SAID: I doubt it. I hope to be busy in the city.

CARLOTTA: I’ll come in with you today. I’ll let you know about the winter.

SAID: I wish I could help you.

CARLOTTA: I don’t need help. It’s the way you feel when you know it’s real. I’m no more helpless than you are.

SAID: If you need money, just tell me.

CARLOTTA: Do you mean that?

SAID: Try me. I’m not rich, but I have more than I need.

CARLOTTA: That’s rich.

IRENA: How much money do you have, Said, if you don’t mind my asking?

SAID: Well, I have this farm, and the apartment in New York, and the house in Malibu is half mine.

IRENA: How much liquid?

SAID: Not much. No more than a few thousand.

IRENA: How many?

SAID: Ten or twenty.

IRENA: How much is your income?

SAID: I have more than I need.

IRENA: That sounds so lovely. Such a lovely expression. Isn’t that a lovely expression, Carlotta?

CARLOTTA: I don’t need money, I need a job. But I don’t want to be your secretary so don’t feel you have to ask me.

SAID: I get about twenty-five thousand from my uncle’s estate. That isn’t enough unless I make a chunk of money from my writing, which fortunately I’ve been doing pretty well with.

IRENA: I still can’t figure out if you are rich or not.

SAID: I’m not rich but I will be rich when my father dies.

IRENA: So you are a rich person without actually being rich, at this point.

CARLOTTA: But you are not poor. You never could be poor.

SAID: In my country we were the rulers.

IRENA: I forget that. Would you want me to take the veil?

SAID: Do you not think the veil is beautiful?

IRENA: Have you seen the veils, Carlotta? Show her the veil, Said.

CARLOTTA: You mean the real veils they wear? No, I have never seen them.

SAID: Really, must you, Irena?

IRENA: Come on, don’t be such a dry stick.

SAID: Oh all right. (Producing veils from a chest.) They are vry beautiful. Try this one on, Carlotta. Irena will help you.

CARLOTTA: I’d like to.

IRENA: Have you been to Persia?

CARLOTTA: No, never. I’ve never been anywhere.

IRENA: I went with my husband to Shiraz. That’s all gone now, I expect. I thought it was horrid. Everybody was only doing it for the money and the glamor. What kind of art is that in this day and age? (CARLOTTA is veiled. SAID turns on Persian music.)

CARLOTTA: What do you mean?

IRENA: You have to ask yourself, if this was the last gasoline in the world, would you take this trip?

SAID: That’s the kind of existentialism I don’t subscribe to. I used to, but I don’t anymore.

(He puts on the other veil. He and CARLOTTA are both covered by the black veils from the tops of their heads to the floor, with only their eyes showing. They begin dancing for IRENA in the sunlit room.)

IRENA: What I want is fearless honesty. I know you are smart, but I can’t believe the half of what you say. It may be plausible, but is it true? I never know. You say it, and you don’t know. (Pause) One of you has everything, the other nothing. Which is which? (Pause. SAID and CARLOTTA, both barefoot, are indistinguishable as they dip and turn to the music.) Now I can’t tell what you might be thinking. I could become quite paranoid. Or not. It may not matter what you think. You can think anything you like. Think anything you can. You are free and I am free. I know how beautiful you are. Only you and I know how beautiful you are.

Scene 4

No setting. Darkness.

ART (Voice from the void): Fifty years ago I decided I am who I am. Maybe a hundred years. More. I don’t know. Long ag. I may not be perfect, but this is as close as I am likely to get. This is the person I am. If you want to love me, love the person I am. (A spotlight picks him out, 200 years old, standing still. Pause.) Then I had time to think about other things. How did I alone escape destruction? Am I the protected messenger of another world? What is my message? Am I especially smart? (Pause.) Until I was fifty I was alone all the time. My childhood had been strange, what little I could remember. I had lost my mother long before. For many years I tried to find my father, and then my father died. Friends were precious, but they went away on business of their own. (Pause.) Once I was fifty I would not live without a woman. This is the story of my life. (Light out. From the void) This is the beginning, and so I will begin from now. I begin from fifty. I am not quite fifty. The year is 1984, at the beginning of the year. (Light on falling snow. He is seen in the prime of manhood, walking with a beautiful woman who is unseen. He speaks to her.) I can never be without music. I need it like a vital vitamin, like food, no, like a drug, and I do know drugs. Like a drug I am hooked on, without which I might as well be dead, that’s the way I feel. Hook me up to the machine. I take it like aspirin, to avoid getting a headache. I don’t mean music in the background, either. I give it my full attention. Take Monteverdi. It’s legal. It’s cheap. It is harmless to the body. You are cold, my darling? Come in here. (They disappear. Voice from the void) About myself I could never learn enough. My exemplary experience. Solitude. Boredom. Emptiness. Imagined death. It’s a very simple kind of lonely love song. (Light finds him on the phone.) Nothing is going to happen. You’re hysterical. Nothing ever happens here, to us. Things happen to other people. Things happen to people in other countries. We are immune. We feel so empty we wish something would happen even though it would have to be worse than what isn’t happening now, which is perfect. You have to agree. (Silence.) I am not trying to be funny. Well, maybe I am. Come on, cheer up. Cheer me up, don’t bring me down. Don’t present yourself to me in a funk. Who needs a friend in a funk? (Hangs up, disgusted.) They would call me up all the time, old friends I really had loved, to tell me about their immediate problems, breaking up, wanting to break up and not doing it, working too hard, unable to work, frustrated. They thought I could help them. I was interested up to a point. (The phone rings. He answers.) Hello… No, I have hardly seen him since I did his play… Sorry, I don’t talk about other people. I love you all. No, I am married. To a woman. Of course I am married. It is unthinkable not to be, once you get the idea, and someone is there… What is this, an interview? Some kind of therapy?… No, I live alone… Look, I am not going to talk about my personal life for a magazine like yours. It is none of your business. I don’t want you to write anything about me at all. I am not straight. I am not gay. I am not a reclusive eccentric. I am not attempting to live a normal life in spite of my celebrity. My wife is not likely to identify herself with me. Any children we may have can be trusted not to tell the truth about us. I value your desire to help me with my career. I suggest you buy a ticket to the show. (Hangs up.) I have asked my friend Carlotta Mendez to represent my wife in this performance, and she has courageously agreed, without knowing precisely what will be expected of her. I would like to state explicitly what ought to be obvious, that this representation does not necessarily coincide with my actual wife Madeline’s actual point of view. Her point of view is clearly expressed in her show of paintings at the Inanna Gallery, which I urge you all to see. The address is given in the program. Carlotta? (CARLOTTA appears as a spry 200-year-old.) How does it feel to be two hundred years old? (Pause.)

CARLOTTA: You tell me.

ART: Well, I will. You talk to the people while I change. (Exit. Pause.)

CARLOTTA (Hesitantly): Events… become wider spaced… You start to be… impatient… Crisis… before you’re fifty… Nothing… seems to happen… You change… everything… Nothing… changes… Time… running… out… Let it… stop… Every day… the same… Awake… like sleep. Work… the same… Will… stone…

ART (Voice from the void): My wife now shows the essential actions.

(CARLOTTA, moving at a relentlessly steady slow tempo, pantomimes the following sequence: waking, rising, bathroom routine, dressing, eating, clean-up, painting for a long time, eating, resting, making love, painting for a long time, having a drink, reading the paper, cooking, eating, singing, dancing, talking, talking on the telephone, getting ready for bed, reading in bed, going to sleep. Simple props are there when she needs them: a table, an easel, a bed. Naturally this takes a very long time, and while it is going on, ART comes in age 50, in city clothes, at normal fast tempo, talking to CARLOTTA but paying no attention to what she is doing.)

ART (Putting down his briefcase): Hello, darling, here I am at last. How are you? Tired as usual? What a day, what a day. I’m exhausted. Something is terribly wrong with my life. I shouldn’t be so exhausted every day. I haven’t done anything. I’ve had a good enough time. As soon as I start for home I start yawning. It’s truly bizarre. I yawn and yawn. I feel as though I am turning myself inside out, turning time around, running the day again upside down to get it right. All I can think about is a drink but when I get here I don’t even want one. You didn’t wait for me, did you? I don’t blame you. Where are the children? Watching more tv? I hate this. I don’t blame you. (Goes to his briefcase and takes out a script.) Listen to this. This is what I was working on today, if you can call it work. But if it isn’t work, what is it? (Reading) Tell me, Louise, is this what a man deserves at the end of a long hard day at the agency? Macaroni casserole again? Is this an appropriate reward? I work hard. I do my best for you and me and the children. Why are you so depressed? Louise: I work too! I may not be as efficient as your mother but I try. You think it isn’t work to send the children off to school, and make the beds, and clean the house, and do the laundry and the marketing, and be there when they get off the bus, and listen to them and help them with their homework, and make dinner and be cheerful when you come home all burned out and angry from the agency? Ralph: It may not be easy but it isn’t work. You don’t get paid for it. You get to stay home all day and be yourself. Louise: I’m sorry, Ralph. If you don’t understand, it’s hopeless. I love you but I can’t take it anymore. I have to leave you. Ralph: Go on and leave. You’ve been threatening to leave me for the past three yeas. I’m sick and tired of it. Go on and go. It won’t be the first time my heart’s been broken. The last thing in the world I want is to make you unhappy. (As himself) Jesus! (Throws the script on the floor.) I have to take a little nap. Call me when dinner is ready. (Leaves. CARLOTTA continues her pantomime. After a little time, ART returns, 20 or 30 years older, moving rather more slowly.) Good morning, honey. (Kisses her; she is painting.) I love these autumn days. This is one of my favorite times of the year. I was awake in the night. Were you awake? I didn’t want to wake you so I tried not to move. Your breathing was slow and even. I was thinking about the little ones. If you died I would need them. Does that sound cruel? (Pause.) I would be alone. (Pause.) I hear music. Do you hear it? Faintly, coming from afar. An orchestra. A soprano. Birds calling, answering, repeating the song. Scampering feet in the fallen leaves. A dog? A child? A chipmunk? The pleasure is far away. I remember how close it used to be, how much I liked this once, often, and so I come to it again, again. How bright these colors were. How full my heart. (Sees the script on the floor and picks it up.) What’s this doing here? (Reads in it, shakes his head.) God, Louise. Thank God I don’t have to do this rubbish any more. Those idiots! We were insane, lost in our madness. It was true enough, but what a truth! (Puts the script away; “acting”):

Night knocks on my window like a mother

frightened for her children left alone.

Left alone not knowing she’s the night

herself, she tries to rape my solitude.

I am frighted in a safer way, knowing

my house is safe against the hurricane.

Somewhere else it might be uniforms,

bacillus, ice. It might be war, the end

of all we’ve won, instead of simple death.

It might be you, though, warm and soft

in bed where I’m not glad to be alone.

Ours are the nights to live like kings

and queens and princesses and princes.

Like a tree, like a perfect glass.

(Himself) That’s more like it, hey? Shall we go out afterwards for a drink and a steak? I’d like that. I want to live forever. What would you do if I died? Isn’t that a laugh and a half? God, I’ve got to get out of here. Rehearsal can’t start till I get there. I’ll call you later, before the show. (Rushes out. CARLOTTA has been reading in bed. Now she switches out the light. A dream light falls on the bed and on another spot on the stage where ART appears as he was at the beginning of the play. She rises dreamily and dances toward him.) You were good, Carlotta, you were very good. This performance has made you a star. You are a legend now. I knew you from the start, my love. I love you.

CARLOTTA (Dancing, laughing): Come over, come over. I want to take you to bed.

ART: Later. Perhaps.

CARLOTTA: I hate the Cedar.

ART (Turning hateful): I don’t care.

CARLOTTA: I hate them all.

ART (With a hideous expression): You were terrible. You forgot my cues. You were ugly. You were fat.

CARLOTTA: I want you. (Continues dancing lyrically.)

ART (Laughs insanely): They all want me. They all have wanted me for years. I kept myself pre. I kept my body perfect for my art. (Turning indifferent.) You’re nothing, my dear. I’ll call you in the morning. You can leave a message on my service. Any time. (Laughs. Fades out. She falls on the bed in the dream light, thrashing and moaning. As soon as he can, ART rushes to her and takes her in his arms. They are both 200 years old.) Madeline, Madeline, wake up, wake up! It’s a dream, you’re only dreaming. (The light changes back to normal as she weeps on his shoulder in his arms.) There, there, my love. It was only a dream. I’m here now, it’s really me. Ah, my sweet, I know, I know. The dream is where the feelings live, the only place we’re young again, and everything is possible, what’s lost is found, the dead are alive again, the love you never see smiles at you, you dare to speak, he offers himself again, this time you may do no wrong. Stop crying now. Carlotta, stop.

CARLOTTA (Gasping): I can’t. I can’t stop.

ART: Carlotta, stop! Carlotta, this won’t do! I command you to stop this crying now! Now! This instant! Come then, my dear. (He takes her out, weeping hysterically. Pause. He returns alone.) She might have died. Who would have married me then? I seemed so old. I am old, but not too old. This is the middle of my life. I’m good for another hundred years. A simple diet is the secret. A little food. No meat. No drink. A simple tolerance. This is the story of half my life. (He lies down on the bed. The lights change to the dream light. SAID appears as at the beginning of the play.) You think_ _I am a monster but I was only stupid, I didn’t want to hurt you. I was unaware.

SAID: Not true.

ART (Rising): I would have spoken with you afterwards, if there ever had been time. I would have given back everything I took away, believed you, listened, trusted you. I knew you were a person just like me.

SAID: Not true.

ART: How can you say that?

SAID: I’m not like you.

ART: I don’t mean you, I mean… anyone. I mean everyone that came before. It was only yesterday my life began. No, not yesterday, today. Everything is gone. Everyone is dead. Anything at all can happen but it doesn’t. Everything would flash with meanng if it did, not slowly fall and rise and fall the way it does. My wife remains, thank God, the other half. How can I possibly explain to you?

(With a strangled, inarticulate cry of rage, SAID throws himself on ART, knocks him to the floor, and begins beating him and trying to strangle him. ART fights back but rather feebly. The two of them roll on the floor in a desperate struggle. CARLOTTA lets this go on as long as she can stand it, then rushes in and violently pulls SAID off.)

CARLOTTA: Stop it, stop it, you fool! He’s old, Saïd! He’s old!

(SAID, thrown halfway across the stage, screams a long blood-curdling scream; the lights change back to normal, then dim quickly out.)

ART (Voice from the void): The children went away, and I decided not to follow them. Nothing was left. We had each other, as they say. If I woke up and saw daylight, I decided I was happy. (The lights come up and find him walking, very slowly, 200 years old, with an unseen beautiful woman on his arm. He speaks to her.) It doesn’t matter who I am, but I’m glad that I exist, for your sake. There are so few of us. Listen (Stops.) Have they started the concert without us? I know this music all so well. I love to see the young people play it once again, so serious, so perfect and exact, so quick, so seemingly spontaneous, as if no other note will do. Where could they be taking us that we’ve never been before? No, they’re only tuning up. (Resumes movement.) Is this year like the ones before? I don’t remember. Every time it seems familiar and yet not the same, the same and not the same. Are you cold, my darling? Come in here. (They disappear.)

Scene 5

The lobby of the theatre. The pictures are all of ART, the posters for “The Story of My Life.”

Several PLAYGOERS burst in through the center doors putting on their coats.

FIRST PLAYGOER: The second half was better than the first.

SECOND PLAYGOER: I don’t know. I thought the first half was better than the second.

FIRST PLAYGOER: I mean the first half of the second part.

SECOND PLAYGOER: My favorite part was the second half of the first part.

FIRST PLAYGOER: I’ll never forget that part.

SECOND PLAYGOER: Me neither. (They go off.)

THIRD PLAYGOER: I think it’s hopelessly old-hat.

FOURTH PLAYGOER: Do you have the car keys?

THIRD PLAYGOER: I really much prefer neo-realistic post-modern super-naturalism. I never did like the avant garde.

FOURTH PLAYGOER: I have the keys but I don’t know what I did with the ticket.

THIRD PLAYGOER: Don’t you?

FOURTH PLAYGOER: Oh, that’s right, we parked on the street.

THIRD PLAYGOER: Don’t you even care what I think?

FOURTH PLAYGOER: What about?

THIRD PLAYGOER: About anything. What’s the point of going to a play if we can’t talk about it afterwards? Joyce, I’m serious. This is not exactly fun, you know.

FOURTH PLAYGOER: I’m sorry, but I really cannot remember where we parked. Can’t you see it’s really bothering me?

THIRD PLAYGOER: Did you like it? Do you think it’s an important piece? Did it say something to you? Did it make you laugh and cry? Do you feel better now? Was it worth the fifty bucks? (SAID appears.) Oh look, isn’t that Saïd Raj? (Goes over to him.) Excuse me, aren’t you Saïd Raj?

SAID: Yes I am.

THIRD PLAYGOER: How did you like the play?

SAID: How did you like it?

THIRD PLAYGOER: Oh I just loved it. I think it’s the best thing he’s ever done. I think it’s an absolute breakthrough, don’t you?

FOURTH PLAYGOER: Honey, we really have to go. Excuse me for interrupting.

SAID: That’s all right.

THIRD PLAYGOER: Joyce, this is Saïd Raj. You remember him. The playwright.

SAID: Enchanté, madame.

FOURTH PLAYGOER: He didn’t like it. He thought it was ridiculous. (To THIRD PLAYGOER) Do you want to go home with me or not. I’ll leave you here if you like. If this is the milieu you prefer.

SAID: Excuse me, please. (He goes to the door of the manager’s office and knocks.)

FOURTH PLAYGOER: Did I embarrass you? I’m sorry. Really. Come on, hon. (They go out.)

FIFTH PLAYGOER: I was disappointed.

SIXTH PLAYGOER: I am never disappointed.

FIFTH PLAYGOER: I read what Edmund Simpson wrote about it, you know, the ‘exemplary consciousness’ article, and I must have formed an image of it in my mind more… more… more…

SIXTH PLAYGOER: I never read reviews.

FIFTH PLAYGOER: This wasn’t a review.

SIXTH PLAYGOER: Is your roommate home?

FIFTH PLAYGOER: I don’t think so. She’s in Tennessee.

SIXTH PLAYGOER: I go to everything.

FIFTH PLAYGOER: That must cost you a fortune.

SIXTH PLAYGOER: Maybe I’ll just put you in a taxi. (They go out. SAID is still knocking on the door to the manager’s office. EDMUND and IRENA enter from the theatre arm in arm.)

IRENA: Do you need me to come with you to the paper?

EDMUND: Well, I would like it. I’d like you to look at what I write. It’s just so dreary coming home alone, even if we’re too tired to talk. It’s all right, though. (SAID comes toward them.)

IRENA: Saïd, what’s the matter? You look spooked.

SAID: He said he’d be in the office after the show. Can I have misunderstood?

IRENA: The play was all right. What’s the matter?

SAID: I have never been so humiliated in my life. He can’t do this. It’s all lies. He isn’t married. I’m having him stopped. I already talked about it to my lawyer.

EDMUND: Would you want him to tell the truth?

IRENA: Edmund, be still.

SAID: It was my idea about the old people. I’m sure it was. We talked about it several times. We were planning to do it together. I went to Egypt! Now he has used it up, ruined it. This is nothing like what I wanted to do. He never would do what I wanted. He never liked my work.

ART (Entering): That isn’t true and you know it!

IRENA: Of course it isn’t true.

SAID: You all think I am no good without him. But the opposite is true. He is no good without me.

ART (Laughs): Well, what am I supposed to do? I’m only forty-eight years old.

SAID: Accept me. Take me back.

ART: Don’t be silly.

EDMUND: Darling, I have a deadline looming over me.

IRENA: Just a minute, Edmund.

EDMUND: I don’t want to hear this. I feel I am being compromised, or at least confused.

SAID: Now you’re being silly, Edmund. You know perfectly well what you think of his play.

EDMUND: As a matter of fact I do. I had perfectly distinct responses as it went along.

CARLOTTA (Entering): Well, chaps, who will take me out for a drink?

IRENA: Carlotta, you were wonderful. How do you feel?

CARLOTTA (To ART): That’s the last time, my man. Once was more than enough.

IRENA: You mean it was really not rehearsed?

ART: Shut up, Carlotta. Please.

CARLOTTA: When was I supposed to rehearse? I was with you. Don’t you remember?

SAID: And where did you learn to do this? From me! And where did you turn when your husband squiffed you? To me!

ART: So what, Saïd? Honest to God, you still think you own us all! I don’t give credit! I don’t mention anyone! It doesn’t count! I couldn’t name all the people I’ve been to bed with. Could you? The world won’t wait. People have their own lives. Come on, Carlotta.

CARLOTTA: I’m not coming with you. Ta, everybody. (Leaves.)

SAID: I’ll come with you.

ART: No, babe, I have a date. Sorry. (Goes.)

IRENA: Go ahead, Edmund. I’ll meet you there. (EDMUND goes out. Pause.)

SAID: You won’t have me, then, after all.

IRENA: I think you decided this yourself.

SAID: I’ve changed my mind.

IRENA: It’s too late.

SAID: You should have waited.

IRENA: I did wait.

SAID: I’ve changed.

IRENA: Perhaps you have. Or perhaps it’s jsut the pressure of events. It is possible to change, I do believe, but frankly, love, you don’t seem changed to me.

SAID: No, really, I mean it, I’m ready now. Try me.

IRENA (Laughs): This is something, isn’t it, you boys wanting to be married now. What do you want from us? Nurses? Mommies? Maids? (Laughs) Sorry, I know I am vulgar and stupid. You don’t want me, my dear. You don’t want me flossing my teeth. You don’t want me spending your money, enjoying my own opinions, laughing in the kitchen with my women friends. You don’t like me to have my period. You don’t want my children putting their feet on your furniture. You don’t like me to talk. (Touching him.) There now, darling, let it be. I have worked it out with Edmund, I’m content, and you’re contented with your solitude, you know you are.

SAID (Crying): I’m not, you know, I’m really not.

IRENA: Well, I know you’re not, but why are you telling me? Does your change depend on me?

SAID: Yes.

IRENA: No good, Saïd. I’m not in the business.

EDMUND (Returning): Are you ready, Irena? I have a taxi waiting.

IRENA (Kissing SAID): Goodbye, my dear. I’ll call you. (Goes out.)

EDMUND: Can we drop you somewhere?

SAID: No. Thank you.

EDMUND: Good night, then.

SAID: Good night. (EDMUND goes. Most of the lights go out. Persian music drifts in. SAID dances in the empty lobby, and as he dances, speaks): They are lighting candles for me in the palace. The women are all the same. The marble floors are shining through the carpets on the sand. The lips of the men are wet. Naked boys are dancing in the moonlight. My father keeps a suite at the Paris Ritz. He is famous for the beauty of his wives. At least three of the Cadillacs will meet me at the airport. The wind is hot. I am traveling alone. (Dances.) My knowledge must not be lost. How to make a perfect cup of coffee every time. The ages and special talents of the servants, and how to give them orders. The numbers. The differences between us. How long to wait before you speak, and what to say. (Dances.) This is the step. This. (Repeats it.) This is the movement of the bedouins when their wives are far away. This I remember from the ancient times. This the blood remembers. (Stops. Silence. CARLOTTA comes in. Silence.)

CARLOTTA: Come on, Saïd. I’ve come to take you home.

SAID: Good. Good. (Pause.) How have you been? (Pause.) My secretary has left me, you know. She had her baby. (Pause.) Another girl is coming in the morning, the daughter of one of my former students. I have two million things to do. She says she can type. (Pause.) I hope so. We have to do the application for the Persian ceremonial theatre project. I went to Washington last week and got a good reaction but we have to do the application properly. They won’t even read it unless it is perfectly typed. I wrote the introduction to the carpets show at Asia House, you know, and there’s a huge party tomorrow for the opening. My book is coming out next week, and I’ll do “Good Morning America” for that. It took long enough. (He continues talking as they start out, arm in arm.) This is the first volume of my memories. The novel is not right. Did you get my letter? I went to Houston for the revival of “Scales,” but I was sorry I had gone. Did you see the reviews? Ralph was marvelous but it did seem rather warmed over. I am sick and tired of failure. Everything I do from now on has to have at least the possibility of some success. (His voice has faded out to silence.)

Copyright © 1983. All rights reserved.

“COME IN HERE”

In 1994 I was living in Santa Barbara, trying to find my way back to theatre, and had the opportunity to direct a one-act at the Ensemble Theatre Company. I extracted the play-within-the-play from “Half Life” and did it under the title “Come In Here.” It did not entirely make sense out of context, but it had a certain theatrical je ne sais quoi, as Phil Brandes’s review nicely conveys.

Production Credits

“Come In Here” was presented by The Theatre Zone at Ensemble at the Alhecama Theatre, Santa Barbara, California, in May 1994, on a triple bill with “A Kind of Alaska” by Harold Pinter and “Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All for You” by Christopher Durang. It was directed by the author with the following cast:

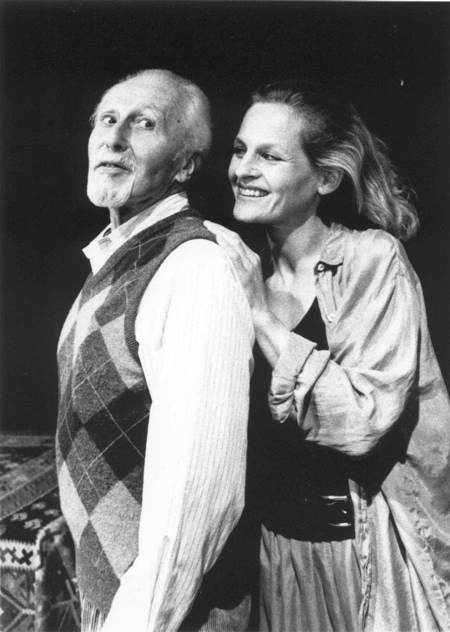

| ART | Dick Spahn | |

| CARLOTTA | Gwynn Van Seenus | |

| SAID | Ben Liberman |

Reviews

from the Santa Barbara News-Press, May 22, 1994

by Philip Brandes

… If the content is obscure in Pinter’s play, it’s practically indecipherable—also by design—in the evening’s opener, Michael Smith’s short invitation to “Come In Here.”

The destination in question is the psychic domain of Art (Dick Spahn), a 200-year-old actor surveying and at times reliving his life in the theatre. Switching unpredictably between meditative detachment and intense emotional outbursts, Spahn (accompanied by Gwynn Van Seenus and Ben Liberman) reveals his life as a prison with boundaries defined by theatrical convention.

Smith (who also directs) has geared his pitch squarely to the intellect, with self-reflective twists that turn the artifice of theatre back on itself. His piece is a sometimes frivolous, sometimes savage cerebral challenge couched in the confrontational staging of the avant garde ‘60s. What it’s really about is anybody’s guess.

But before you get too caught up in trying to unravel the puzzle, remember that prideful intellect left unchecked can be the enemy of Faith…