“Double Solitaire”

Production Credits

“Double Solitaire” was first presented in September 1973 at The Changing Scene, Denver. It was directed and designed by the author and performed by the following cast:

| FATHER | Dennis Stull | |

| MOTHER | Melanie Kern | |

| DAUGHTER | Patricia Madsen | |

| VISITOR | John Simcox | |

| NEIGHBOR | Nancy Mangus | |

| PETEY/JIMMY | Greg Boyle |

and in Part 2: Jane Larew as DAUGHTER, plus Sid LaBarr, Tom Johnson, and John A. Mancini

| MUSICIANS | John McClure | |

| Erica Bramesco | ||

| Mark Grant |

Most of the music was by John McClure. Russ Stevenson made the wonderful truck.

“Double Solitaire”

a two-part play

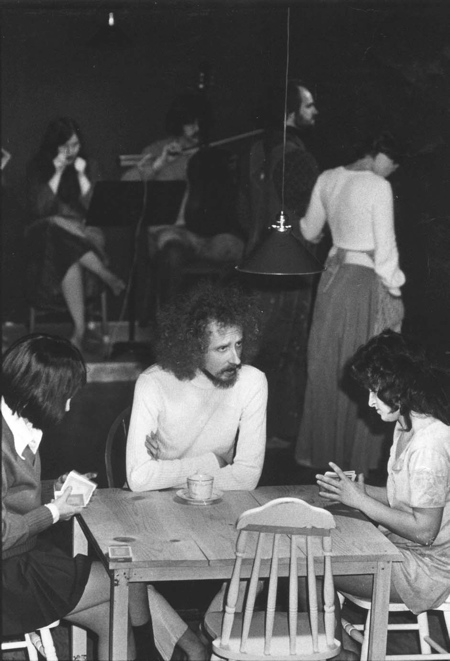

Patricia Madsen, John Simcox, Nancy Mangus (foreground), Dennis Stull and Melanie Kern (background) in “Double Solitaire”

Part 1

Downstage left the front of an old pickup truck noses onto the stage. Downstage right a square wooden table with four chairs. MOTHER and DAUGHTER are sitting at the table playing double solitaire. They are in profile; MOTHER has her back to the truck. Upstage center a group of MUSICIANS, playing. FATHER stands looking down into the engine. Tableau.

Music stops.

FATHER (into truck): Been good to me, been good as gold for all these years. I’m a lucky man, I know it. I didn’t know a thing, I might as well a been asleep or done it with my eyes closed. But I wouldn’t a missed the pretty sight of her. We was rollin’ through a tunnel of sunshine, her lighting it all up and me not knowing whether to whistle or die or say something or stop and take a piss. She was humming soft as satin. I didn’t care where we were goin’, I was happy like a fool. That musta been, lemme see… Wellsir, that was the smartest move I ever made. How could I a knowed, that’s what gets me. I took my chances and I played it straight and won.

MOTHER (turning and calling): You all ready for some tea?

FATHER (answering, mellow): Time’ll come. (Into truck) Better get on with it now. I don’t want to bore you with the old this and that. But memory’s sweet.

TRUCK (in a slow, resonant, metallic voice): It’s rare to meet a happy man. I like it.

FATHER: Well, that’s good. You’d be crazy not to. Have some fun out of it. Don’t be afraid to get yourself dirty, it all washes off. Feels good to touch things, find out how it all fits together.

(Music. Brief tableau.)

DAUGHTER (Starts talking in mid-sentence when the music cuts off): … after the party and I felt terrible about it. It was giving me a terrible headache and I was trying to scream but they kept giving me hamburgers. It was all I could do to eat one before they were giving me another. All those boys. I hated it. I hated every minute of it. I got out of the truck in the middle of the parking lot. I can’t stand that song that keeps running through my head. It’s playing on all the radios in all the cars. How am I going to get home? What will I tell Daddy?

MOTHER (flatly): Shut up.

(They play in silence. After about a minute DAUGHTER again starts talking in mid-sentence.)

DAUGHTER: … the only one there wearing red? What do you want from me? It’s not me, it’s my dress.

MOTHER: You knew what you were doing.

DAUGHTER: I’ll get sick. I’ll turn their fish faces into tear-streaked masks of tragedy. Don’t you dare look at me like that. They sent me home in an ambulance. I was in a coma. Nothing they can do will wake me up. They don’t care. Nobody cares about anything.

MOTHER: Stop talking.

(They play in silence. After about a minute… )

DAUGHTER: … cause I can’t see the words. I need new glasses. They never change the light bulbs. They don’t really get the windows clean. The sun never really shines anymore anyway.

MOTHER: Sh.

(They play in silence. After about a minute… )

DAUGHTER: … my period. It always happens that way.

(MUSICIANS cut her off by starting to play. They play for about a minute. Music stops. Slowly VISITOR extricates himself from under the truck. He is immaculate in white. Needlessly, he brushes himself off. He faces FATHER.)

VISITOR: Are you sure you want to sell her?

FATHER: I’d sell my wife if she’d go.

(Music. During music FATHER takes VISITOR “into the house.” Polite introductions, in pantomime. DAUGHTER gathers up the cards and MOTHER brings tea. The table and chairs are on a wagon that imperceptibly creeps across the stage toward the truck. The table is lit by a hanging overhead light that travels with it. The MUSICIANS upstage have a similar light that also jiggles and sways a little. When all are seated, MOTHER and DAUGHTER in their places, VISITOR upstage, FATHER downstage with his back to the audience, music stops.)

MOTHER: One lump or two?

VISITOR: Uh. Fine.

FATHER: You been around here long? I know I’ve seen you before.

VISITOR: No, I only come here in the— uh—

FATHER: ’Tain’t always like this, you know.

VISITOR: No, I bought the— uh—

MOTHER: Milk?

DAUGHTER: Mother!!

VISITOR: No, my— uh—

MOTHER: Or lemon?

FATHER: That’s all right. Now I get it.

VISITOR: They’ve—

MOTHER (to DAUGHTER, forcefully): Grow up.

(Long pause. They all drink tea except the VISITOR, who is paralyzed with embarrassment. Eventually):

FATHER: My cousin Violet lives down in Arkansas. She’s married to a peach farmer named Satterlee. Frank Satterlee. Married him on her 18th birthday. I was 16 and I had a big pimple on my cheek that showed in all the wedding pictures. I went down there every year for the peach harvest after that until I married my wife and we moved out here. I feel incredibly close to Violet. It’s as if we’re the same person living the same life, except in different bodies and situations. Everything that happens to her happens to me two years later in a different form. It completely wipes out time. Nobody else can see it, they don’t think we’re any more alike than what you’d expect, but it’s on another level than that. Well, she lost her boy Petey in the war. He was run over by a trolley car in Saigon. Cut him in two.

MOTHER (who has been thinking of something else): Excuse me. (She goes “out” into the yard. Soon the sun will set.)

FATHER: We don’t express our feelings much, not the bad ones, which you might think means we bottle them up inside, you know what I mean, but we don’t. She’s a fine woman. She makes me feel proud to be a— (Stops abruptly. Pause.)

VISITOR (with great difficulty): I believe you.

FATHER: It’s a big decision for a young man like you, in what you think is the prime of life. You might as well relax, don’t make no difference at all if you tense yourself up. There’s no secret drama going on. It’s just us.

VISITOR (gasping): What do you mean?

FATHER: Violet, I mean Louise, tell him about your school. Louise is the captain of the hockey team.

DAUGHTER: Well, I used to be.

FATHER: She’s out of school now. Whatcha been doin’ with yourself, hon?

DAUGHTER: Well, I went down to the King Soopers to buy food for the rest of the week, and I bought light bulbs and laundry detergent, and I bought some rock salt for the driveway next winter, and I bought two dozen yellow roses and some ferns, and I stopped off at the garage to buy two new tires for my truck. I talked to Jimmy, you know, the fella that works at the garage, I told you about him, he wants me to trade it in for a ‘68 Ranchero. Who’d want to do a thing like that? I don’t ever want to see him again. I went into town after that to shop for some clothes. I need some new shoes and a new sweater and I looked at one of those plastic things that change color when you rub your hand over them, but I couldn’t find anything I liked. I went shopping for some new records but I couldn’t find anything I wanted to hear. I had lunch in Woolworth’s. That’s my favorite place in the whole world.

FATHER: What did you have for lunch?

DAUGHTER: I had a peach delite and dry rye krisp and a cup of tea with nothing. After lunch I went to the health food store to buy some peanut butter and granola for Jimmy and then I bought a kit with seeds and everything in it for growing herbs and then I bought an electric toothbrush, they were on special, and I went shopping for a trailer in case we get to go someplace sometime but I didn’t find anything I liked, and then I bought a couple of magazines. On the way home I went by to see Jimmy but he wasn’t there. (Pause.)

FATHER (to VISITOR): Take your time if you want to, but you might as well decide tonight. Take it as it comes and don’t make the same mistake twice. Have another cup of tea (Pours) and talk it over with Violet. No point in me talking to her that way. I look for advice but it’s like talking to myself. I mean my same self. I’ll be out by the truck if you want anything. (He joins MOTHER “outside.” The light is softer and golden and rosy. Music starts softly.)

VISITOR: Was that supposed to be a joke?

DAUGHTER: What?

VISITOR: You don’t have to pretend we can’t communicate.

DAUGHTER: What am I supposed to say to that?

VISITOR: Be sincere.

DAUGHTER: I am sincere.

VISITOR: Sincerely rude.

DAUGHTER: Sincerely yours.

VISITOR: Oh if only you meant that.

DAUGHTER: What’s the matter with you?

VISITOR: I’ve never felt this way before.

DAUGHTER: Why were you so up-tight with my father?

VISITOR (amazed): I’m here! This is me!

DAUGHTER: I don’t think you should buy it.

VISITOR: What?

DAUGHTER: The truck. He doesn’t really want to sell it. He’s a sentimental old fool. He’s in love with it.

VISITOR: And you? Do you believe in love?

DAUGHTER: It’s difficult to talk about love in English.

VISITOR: Do you?

DAUGHTER: I’m not evading the issue. It’s my favorite subject.

VISITOR: What do you know about love?

DAUGHTER: Don’t talk to me like that. I’m not your wife! (VISITOR jumps and cries out in sudden fright.) Hush now, hush, it’s nothing, it’s a dream, it’s the demons of the night.

VISITOR: Are you there? Louise?

DAUGHTER: I’m here, I’m holding your hand.

VISITOR: It’s something, but it’s not enough.

DAUGHTER: I’m here, I’m holding your hand.

VISITOR: It’s not enough, but it’s something.

DAUGHTER: Of course it’s not enough. You have to live your own life.

VISITOR: Who do not follow the gods, they drag.

DAUGHTER: We can talk about something else.

VISITOR: What level do you mean that on?

DAUGHTER: Take me as I am or go away.

VISITOR: Amanda, I didn’t know, I swear. I haven’t seen her since the funeral.

DAUGHTER: I don’t ever want to see you again.

VISITOR: Don’t do this, I beg you. You’re making a terrible mistake.

DAUGHTER: No, it’s not so terrible. I’ve written to his mother. Other men have led useful lives with less than he’s got left.

VISITOR: But he was handsome.

DAUGHTER: And you were a beautiful baby. You’re making such a fuss.

VISITOR: No, I’m all right. Give me a few minutes alone with her, is that asking too much? And then we’ll go. Look, I don’t know what you’re doing to me. We’re getting too crazy.

DAUGHTER: You don’t have to be so miserable. You don’t have to go through life disappointed and half awake.

VISITOR: I know! I get the message! I’m doing it!

(During this exchange FATHER and MOTHER have started dancing in the light outside, not together, but aware of each other. They started very subtly, just moving a little to the impulse of the music to feel their bodies. Gradually they got more into it, revealing aspects of their characters not otherwise exposed, taking impulses from the music. Now NEIGHBOR come dancing in and galvanizes the dancers into higher energy. Still it might be people out looking at the sunset. The two “inside” sit contentedly while the others dance and play. After it ends)

DAUGHTER (calling): Louise?

(NEIGHBOR goes inside and sits at the table facing DAUGHTER. They play double solitaire. VISITOR reacts to what is said outside as if it were thoughts occurring to him for the first time, not heard but occurring in his mind.)

MOTHER (lookng all around): What is it? What is it? Look. Do you really believe the sun is like a giant light bulb, that the light “comes from” the sun? Or that the sound travels from the airplane engines into our ears, like food into the city? Or that time moves steadily forward like the ticking of a clock? Somewhere there’s a secret print-out with all the data I need.

FATHER: It’ll do.

MOTHER: A couple of years ago they thought the whole cosmos was expanding at a constant rate. Everything was always moving farther and farther apart, on every level—molecules, people, I guess, stars, galaxies, universes. It’s an obvious implication of the Big Bang theory. And I believed it, even though it put me in a weird mystical relationship with E equals MC2. Math is pretty mystical.

FATHER: It’s a little flat.

MOTHER: That’s what I thought. It’s not where I’m at. Or you. But I took it in anyway. I didn’t have any choice. It’s too simple, I couldn’t not get it. Well now they think it’s expanding in some places and contracting in others, in a kind of chaotic symmetry, some delirious magnetic pairing off. Some places matter is being created, whatever that means, and other places it’s being destroyed. The black holes. The black holes. What does that make you think of?

FATHER (thinks): It’s quite sinister.

MOTHER: And the other ones burn you to a crisp if you so much as touch them with your brain. The antimatter hypothesis is pure dada. I think it’s a deliberate scam. They’re ripping us off for incredible amounts of machinery. What’s it supposed to be, more conceptual art? Antimatter?

FATHER: Are you angry?

MOTHER (shivers): I mean they’re right but they’re putting it on the most useless level.

FATHER: I love you.

MOTHER: They’re like professors. Most of them are professors. They go into their number and forget themselves, forget they’re doing it, forget whom they’re talking to, forget what what they’re talking about has to do with anything. If you question anything they say they just go farther into it. There is simply no way not to sell out. How can anyone outsmart an institution? Obviously it takes over a whole part of you. A whole part of your life is in its power.

FATHER: I love you because you’re so smart.

MOTHER: They leave out time. Why not postulate an antitime in some places, or time that runs backwards? Or a non-time, a sort of shimmering crystalline stillness that neither waxes nor wanes but burns without consuming itself in a permanence that mocks eternity. As I see it, time is just one of the modes in which anything can be perceived as existing, parallel to space and several others.

FATHER: I love you because you’re so smart and everything else too.

MOTHER: I mean you might as well sell the truck.

FATHER: That’s what I thought.

TRUCK: It’s all right with me.

(Music. PETEY/JIMMY enters in white coveralls, muttering and carrying a spare tire for the truck. It is now quite dark. He has a kerosene lantern to light his work. The music is meditative, drone-centered, slowly transforming without changing. Stars have come out over the musicians. MOTHER and FATHER stand and walk about together quietly and leave the stage for a while and return and leave again. PETEY/JIMMY gets tools and during the following scene jacks up the truck and changes a tire. Meanwhile)

NEIGHBOR: What did he say? Did you see him?

DAUGHTER: I hate him. I never want to see him again.

NEIGHBOR: What happened?

DAUGHTER: I don’t want to talk about it.

VISITOR: You’re being rather rude.

NEIGHBOR: Is everything all right otherwise?

DAUGHTER: Play. (They play.)

VISITOR: I woke up a minute ago thinking I’ve ruined my whole life and now it’s too late to do anything about it.

NEIGHBOR: Really?

DAUGHTER: Play. (They play.)

VISITOR: It’s the kind of thing anybody might think at the wrong moment. It’s a matter of getting right out of bed when you wake up. Why wait for everybody else? Get that delicious feeling some other way. It’s not that delicious. And the thoughts are useless. I can give you a whole analysis of why and how I have wasted and ruined my life, mistake by mistake, as well as a detailed geography of how I… (This fades into a mumble. Meanwhile PETEY/JIMMY’s mumbling has crossfaded up into audibility. The mumbles might be a kind of singing to the drone.)

PETEY/JIMMY: … a functioning jack, a block to put under the diagonally opposite tire to keep the vehicle from rolling off the jack, a screwdriver or other prying tool, and a lug wrench. It’s worthwhile to buy yourself a cross-shaped lug wrench if you don’t already have one. It’s a very satisfying tool to use. The ones they give you are adequate but ugly and awkward. It’s possible to keep the clothes clean, but resign yourself to getting your hands dirty. Fetch the spare from its mount before jacking up the vehicle. The jack is probably rusty and this would be a good time to oil it… (Crossfade.)

VISITOR: … India where there are more possibilities. In another way there are fewer, less. If you take a leak standing up you come back as a donkey. Our personalities are more… confined in spite of all the opportunities we… have for… I don’t have to know anything about you. What difference does it make? Unless you intend to stay in this bag your whole life.

DAUGHTER & NEIGHBOR: Are you talking to me?

VISITOR: Either one.

DAUGHTER & NEIGHBOR: Because if you are I can tell you.

VISITOR: No, save it for the long winter nights when we’re desperate. I never watch TV. I hate TV. Whenever I tell people that they start telling me there are a few good programs. They name a few high-class dramas and documentaries and great old movies. It’s not the programs I hate, it’s the TV. Who wants to look at an electric light? You have to be a complete vegetable. It’s something everybody should do once, like smack. (Crossfade.)

PETEY/JIMMY: … high enough so the wheel is off the ground, but before you jack it up the last couple of inches, loosen the lug bolts a bit. Otherwise the wheel will turn as you put your weight on the lug wrench. They turn one way on one side and the other way on the other side so centrifugal force tightens them as you drive. Otherwise it would loosen them. I can never think which is which. When I think I’m loosening I may be tightening and when I think I’m tightening I may be loosening. But somehow the job gets done. Put the lug bolts in the hubcap. Always put them in the same place and you will never lose them. (Crossfade.)

VISITOR: … out of touch. (He stops. PETEY/JIMMY and the MUSICIANS keep droning, DAUGHTER & NEIGHBOR keep playing. A noticeable blank. He goes on, angrily:) … working these machines they give us to get around in. Why should I? I’m not a product of General Motors.

DAUGHTER & NEIGHBOR (to each other): What is this?

VISITOR: You’re like those gypsy laides in the fortune-telling machines in the penny arcade. Next you’ll tell each other’s fortunes. (DAUGHTER slaps him, hard. NEIGHBOR throws her cards in DAUGHTER’s face and runs out, weeping.)

DAUGHTER: I can’t stand that kind of talk.

VISITOR: What’s the matter with you?

DAUGHTER: You know perfectly well.

VISITOR: What kind of talk? What did I say?

DAUGHTER: Look what you’ve done now. Do you call that a joke?

VISITOR: I was joking.

DAUGHTER: No, I mean Louise.

VISITOR: You mean the cards?

DAUGHTER: What do you care?

VISITOR: I hate that name. Who is she, anyway?

DAUGHTER: She’s my next door neighbor. I’ve known her since we were both six weeks old.

VISITOR: Maybe I don’t. But something is happening.

DAUGHTER: Violet.

VISITOR: What’s her name?

(Crossfade. VISITOR goes out looking for NEIGHBOR. DAUGHTER picks up cards. Table and chairs are by now in the middle of the stage, DS.)

PETEY/JIMMY: …wrestle it onto the pins. This is the moment you’ll wish you’d rolled your sleeves up. Next time roll up your sleeves before you get your—

TRUCK: Ouch.

PETEY/JIMMY: Oh, sorry. Did I hurt you?

TRUCK: No, but pay some attention.

PETEY/JIMMY (finishing with the tire): I didn’t know you could talk.

TRUCK: Yes, I can. (Pause.)

PETEY/JIMMY: Well. Uh. How’ve you been?

TRUCK: Starter’s broke.

PETEY/JIMMY: I can fix that. (He crawls under the truck and out of sight.)

(DAUGHTER lays out a new game. She names each card aloud as she puts it down. The light upstage has become lushly romantic like a dream or nightmare of a high school dance.)

DAUGHTER: Three of clubs, jack of hearts, ace of diamonds… (etc.)

(The drone is overtaken by a new kind of music, sweet, dreamy, danceable. There might be more stars overhead or even japanese lanterns. MOTHER & FATHER and NEIGHBOR & VISITOR dance in tight couples, as if the floor were crowded, moving about the space. As each couple comes downstage right its intimate conversation is overheard.)

VISITOR: Let’s go live in the mountains.

NEIGHBOR: These are the mountains.

(Danceaway.)

FATHER: Don’t worry about her.

MOTHER: I’m worried about us all.

FATHER: That’s sentimental self-indulgence.

MOTHER: Well. Aren’t you the man of ice.

FATHER: You know I didn’t mean it that way.

MOTHER: I mean I love them and it’s all so awful.

FATHER: No it isn’t. Think about yourself too. This isn’t anything to worry about.

(Danceaway. The MUSICIANS sing the song they have been playing. It is about the actual actors by their real names, describing their ordinary personalities at rehearsals and before performance. The song stops when it describes the actors about to go on stage. The MUSICIANS take a break. The two couples applaud the song, then break apart and come downstage into moonlight, the women at right, the men over by the truck. DAUGHTER keeps playing cards in the middle.)

FATHER: Hm, the tire’s been changed. Petey must have been here. Left his lantern. (He picks it up.)

MOTHER: Are you into anything?

FATHER: Well, what do you think?

MOTHER: I don’t like that word, “into,” but that’s what I mean.

VISITOR: She’s a beauty.

MOTHER: I’ve been reading everything I can find on cosmology. It’s an incredible subject. Everywhere you look people have completely different pictures of how everything got to be the way it is and what keeps it going.

FATHER: I’m a lucky man.

MOTHER: Most of them are obviously fanciful. They think the world is fanciful.

NEIGHBOR: What do you think?

VISITOR: Do you really believe in luck?

MOTHER: To us it’s a machine, a ruthless, beautiful, mystical machine. But what we’re seeing is just one possible view.

(VISITOR & NEIGHBOR exchange looks.)

FATHER (into truck): I hope the starter works.

TRUCK: Don’t worry. Be happy.

VISITOR (to FATHER): I’ve made up my mind. That was easy.

FATHER: You’re not going to buy the truck.

VISITOR: I don’t need a truck. Anyplace I need to go I can walk.

FATHER: This isn’t the end of anything.

MOTHER (to FATHER): You always say that.

(MUSICIANS start to play again. MOTHER takes FATHER upstage and points to the stars, speaking to him softly. He has the lantern. VISITOR & NEIGHBOR are left looking at each other across DAUGHTER.)

DAUGHTER (to VISITOR, who is about to be crushed against the truck by the advancing table and chairs): Why don’t you move that chair?

(VISITOR passes the chair over DAUGHTER to NEIGHBOR. The MUSICIANS sing. The rest of the song is very briefly about what the actors are likely to do after the performance. NEIGHBOR dances with the chair. VISITOR stands looking down at DAUGHTER playing cards. During song he leaves, preoccupied. Song ends, music turns back into drone. NEIGHBOR puts down the chair and leaves. MOTHER moves the chair to face DR wall, where a new table edge is now emerging. The card table, three chairs, and DAUGHTER are about to reach the truck. FATHER is upstage with the lantern, peering out at the audience. MOTHER and DAUGHTER lay out new hands. Long tableau. Truck horn honks twice, cutting off lights & music.)

Part 2

The second part of “Double Solitaire” is to be exploded in collaboration with the actors (& additional actors if desired). In the Denver production it began exactly the same as the first part and then diverged as relationships further developed. What follows is the provisional scenario we used and some proposed dialogue for two variant scenes.

The director and actors are encouraged to take the second part anywhere they like.

1. Preset tableau w/ music

2. FATHER talks to truck

3. Brief tableau w/ music

4. DAUGHTER’s complaints; DRUNK (SID) enters from audience, exit, re-enter, removed by TOM

5. Brief tableau w/ music

6. VISITOR & FATHER (2 lines)

7. Introductions (pantomime w/ music)

8. Tea party; dialogue recycles—TOM & GREG as workmen (?)—TOM’s worker sequence? (w/ GREG?)

8a. FATHER’s Violet speech; John M. as Violet w/ birds; MELANIE leaves, replaced by NANCY

9. DAUGHTER’s shopping speech; wrap table

9a. “Damn right!”—TOM & MELANIE sword fight, kill SID, exit

10. New VISITOR & DAUGHTER dialogue—DENNIS & NANCY entangled in nets—GREG through on bicycle

11. Turning dance—full cast

12. “Louise?”

13. Stars/black hole—MOTHER, FATHER; GREG, TOM, JANE, SID

14. Moonlight; moment of decision; Allende vision; FATHER (blind), MOTHER

Scene 2/10

VISITOR: Was that supposed to be a joke?

DAUGHTER: What?

VISITOR: You don’t have to pretend we can’t communicate.

DAUGHTER: I’m sorry, I was thinking about something else.

VISITOR: I’m here! This is me!

DAUGHTER: What’s the matter with you?

VISITOR: I’ve never felt this way before.

DAUGHTER: I’m trying to be straight with you. I’m involved with someone else.

VISITOR: So am I.

DAUGHTER: I don’t think you should buy it.

VISITOR: What?

DAUGHTER: The truck. He doesn’t really want to sell it. He’s in love with it. He’s in love with everything.

VISITOR: And you? Do you believe in love?

DAUGHTER: It’s difficult to talk about love in English.

VISITOR: Do you?

DAUGHTER: I don’t know anything about it.

VISITOR: I don’t know how I got involved in this. I like your father.

DAUGHTER: I’m leaving tonight.

VISITOR: Really?

DAUGHTER: Don’t say anything. Have you seen Violet?

VISITOR: No, not yet. I’m a little nervous.

DAUGHTER: So am I.

VISITOR: Where are you going?

DAUGHTER: New York.

VISITOR: What level do you mean that on?

DAUGHTER: You don’t have to be so miserable and lonely. You don’t have to go through life disappointed and half awake.

VISITOR: I know! I get the message! I’m doing it!

Scene 2/14

(Enter PETEY/JIMMY carrying the lantern and a suitcase. He climbs under the truck. Drone music.)

NEIGHBOR (coming in): Did you see him? What did he say? Does he want to see me?

DAUGHTER (coming in): He’s looking for you.

NEIGHBOR: Maybe I’d better go home.

DAUGHTER: No, stay here with me.

NEIGHBOR: What did you tell your mother?

DAUGHTER: I don’t want to lie about anything.

NEIGHBOR: No.

DAUGHTER: He should be here.

VISITOR (off): Violet? Louise?

TRUCK: Ouch.

PETEY/JIMMY (under the truck): Oh, sorry. Did I hurt you?

DAUGHTER: Jimmy?

TRUCK: No, but pay some attention.

PETEY/JIMMY (to DAUGHTER): Just a minute.

TRUCK: What are you going to do in New York?

PETEY/JIMMY: Study acting. I don’t think I can fix your starter.

TRUCK: I’m not going anyplace.

PETEY/JIMMY: That’s what I mean.

(VISITOR enters, sees NEIGHBOR, stops. She goes to him.)

TRUCK: Don’t tell the old man.

PETEY/JIMMY: He’s a sentimental old fool. Ouch!

TRUCK: Stop talking.

DAUGHTER (to NEIGHBOR and VISITOR): What have you decided to do?

VISITOR: We’re going to the mountains. Somebody gave me a cabin. I have to cut wood for the winter. It’s incredibly beautiful and quiet. All my life I’ve wanted to live in the mountains but I thought it would be too lonely.

DAUGHTER: But you have to do something.

VISITOR: You mean for money?

NEIGHBOR: There’s enough to do just keeping warm.

PETEY/JIMMY (emerging, to NEIGHBOR): That’s great.

NEIGHBOR: Do you have time to look at my truck? I can’t get the tail lights to work.

PETEY/JIMMY: Sure.

DAUGHTER: I’m getting nervous.

VISITOR: We have plenty of time.

PETEY/JIMMY: I’m on another trip but it’s all the same time. (Exit with suitcase.)

DAUGHTER: We’ll come with you. (Exit with suitcase.)

VISITOR: I woke up a minute ago thinking I’ve ruined my whole life and it’s too late to do anything about it.

NEIGHBOR (holding his hand): Hush now, hush, it’s nothing, it’s a dream, it’s the demons of the night.

VISITOR: I know.

FATHER (entering, blind, with cane): Louise?

NEIGHBOR: No, it’s me.

FATHER: Violet? Is that boy here?

VISITOR: I’m here. This is me.

FATHER: The deal’s off. I’ve decided not to sell her.

TRUCK: It’s all right with me.

VISITOR: I don’t need a truck. Anyplace I need to go I can walk. Anyway, Violet has a truck.

(Allende vision?)

NEIGHBOR: We’re going to the mountains. (Kisses FATHER. She and VISITOR leave.)

FATHER (holding up the lantern, peering blindly at the audience): This isn’t the end of anything.

MOTHER (entering, stops; affectionately): You always say that.

(Truck horn honks twice, cutting off lights and music.)

Copyright © 1973. All rights reserved.

Reviews

from the Denver Post, 28 September 1973:

by Arlynn Nellhaus

Double solitaire. It’s grimmer than solitaire in the same way that being alone emotionally when you are with someone else is worse than being alone by yourself.

“Double Solitaire” also is the name of Michael Smith’s new play which opened at the Changing Scene Thursday.

He plays on the meaning of the title and presents the thundering silence of aloneness. Contact points are few—if they exist at all.

One character makes a statement that seems to be sensible, until another character follows up with a statement that cancels the meaning of the precedng one, and then that statement is demolished by the next.

“Double Solitaire” consists more of a situation than a plot. The father, who is mooning over the possible sale of a truck he loves, brings the prospective purchaser into his house to have tea with his wife and daughter.

The daughter is just out of high school. She is full of confusion and has all the answers. The mother takes the father outside to admire the sun and the stars and to make a lovely speech about time. The father’s response is to hug her and announce, “I love you because you’re so smart.”

Into the scene dances the girl next door, who joins the daughter and visitor. Her next dance is with the visitor, and they discover each other. And then the first act fades away.

The first act is presented as Smith wrote it. The second act is described as “exploded in collaboration with the cast.”

The play seems to start over again until a “drunk” wanders onto the stage and puts on a sort of alcoholic “Man Who Dies.” From then on, the audience can expect anything.

Smith’s words persist, with variations. But hearing them in the second act is like looking at a reflection in a stream into which someone is dropping boulders.

The distortions and the unexpected accumulate until lunacy reigns. From humorous, the play becomes hilarious.

The cast does well with the stylized roles. John Simcox’s confused, frustrated expressions are marvelous, and Nancy Mangus’s bare-bosomed second-act dance (accompanied by the music of spoons) is deliciously loony.

Smith uses music in his play like an additional character. Often it is the most eloquent of his characters.

John McClure, who plays guitar and spoons, wrote the lovely melodies. Erica Bramesco plays the flute and jaw harp. Mark Grant adds the sitar.

Smith’s efforts in “Double Solitaire” are sure-handed. The entire production is tight, well thought-out, and impressive.

a letter

Dear Al Brooks and Maxine Munt,

How much I enjoyed Sunday evening’s performance of “Double Solitaire” by the gifted Michael Smith. I have attended X productions on both coasts and have seldom witnessed such artistry. Allow me to congratulate the entire cast for its work and all of those who made “Double Solitare” such a great dramatic experience.

—Jim Burbank

from the Boulder County Town and Country Review:

by Bill and Janet McReynolds

Michael Smith’s “Double Solitaire” is one of the most interesting plays to come along at The Changing Scene in a long while. It is a time/space play more akin to musical composition than to traditional plot-and-character drama.

Questions of relativity reverberate as the cast—which includes the front end of a truck—explore the literal and mythical implications of words. The second half of the play literally explodes, with a profusion of symbolic figures pouring out of the woodwork. An excellent country music band and the expert dancing of Nancy Mangus keep the plotless evening from sagging in interest.

from the Straight Creek Journal, 2 October 1973:

by Pat Rule

“Double Solitaire” by Michael Smith is a double bill with unusual overtones. Unusual because it is not often (one could say never) that a playwright presents a serious work, one he feels strongly about, and then proceeds in the next moment to offer us an open ensemble satire of that same piece.

The first part of the bill is a continuum of time, space, and conceptualized reality. Introspection is replaced by a melodious flow of information. Dance, music, and drama are combined not in a fragmented sort of way, but with all elements pointing to and expressing the same vision.

Backed by the music of John McClure (guitar), Erica Bramesco (flute/jews harp), and Mark Grant (sitar), the effect is like moonglow playing upon water.

Bliss in domesticity and confusion in an attempted relationship cloud one another. It is shown that although lives have a beginning, middle, and an end, they are nevertheless continuous on another level. Time as we know it is transcendable. The innocence and completion that lie outside of eternity really surround us at all times.

The cast: Dennis Stull, Melanie Kern, Patricia Madsen, John Simcox, Nancy Mangus, and Greg Boyle all give coherent performances.

The set, constructed by Russ Stevenson (primarily consisting of one half of a truck) is excellent.

The second half of the show begins normally in a repeat of what we have just seen. This does not last long, however, and soon the stage gushes with a bizarre combination of slapstick and imagination gone wild. The play is up to the actors’ individual interpretations, and soon becomes a relentless satire on itself.

Domestic bliss is wrapped and packaged as parcel post. Instead of transcending time, people become stuck in it. Instant pageantry a la Ken Russell (film: The Devils) is tossed at us for no reason. Space is a whirligig of chracters, caricatures, and fantasy. The black hole of the universe swallows a wandering drunk, gliding grace becomes crude burlesque, and a blind man is left holding the light.

This second part of the bill is aided and abetted by Jane Larew (writing her own speeches), Sid La Barr, Tom Johnson, and John A. Mancini.

To risk raising tarnished monuments, I will nevertheless say that it takes not only humility, but a healthy kind of honesty for a playwright to gear his production in this way.

The impression of the first piece is not lost by the second satirical depiction because every coherent act, or experiences, has its hysterical counterpart, such is the nature of reality.

“Double Solitaire” doubles itself for in the beginning we get the play and the playwright’s vision. In the end we get the play and the actors’ exploded interpretations. There are four elements here: two plays, one playwright, one ensemble. Overall, we get the beautiful music written by (sic) Michael Smith, as well as his strong direction.